Kentish map-makers of the seventeenth century

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

Probate accounts as a source for Kentish early modern economic and social history

Mapping and estate management on the early nineteenth-century estate: The case of the Earl of Aylesford's estate atlas

Kentish map-makers of the seventeenth century

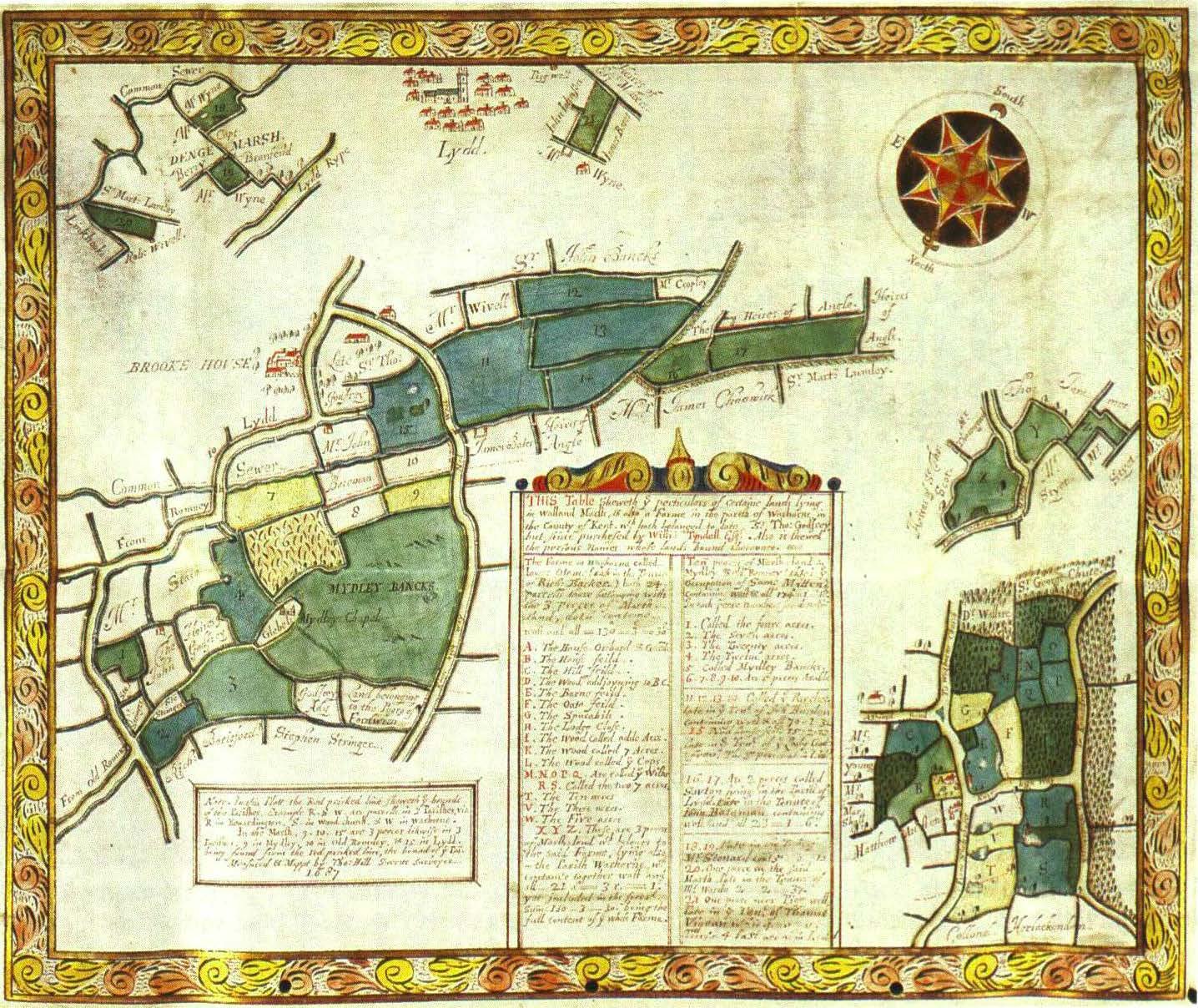

KENTISH MAP-MAKERS OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY F. HULL The history of cartography is usually examined in terms of global or national considerations with early examples revealing struggles with the problem of projection and the depiction of considerable areas of land or of coastal regions. Thus the beautiful maps of countries and counties have attracted much attention and have become popular as items of decoration and the works of Christopher Saxton, John Speed and many others grace the walls of our homes. Yet, alongside this development of printed maps for sale, often originally in complete atlases, there was the purely functional work of the local surveyor, drawing maps for some local magnate or corporation without the need to consider problems of the earth's curvature and leaving a fine legacy covering the period c. 1575 to c. 1850. The number of persons engaged in this activity - land surveyors, draughtsmen and the like - runs to many hundreds, and it is considered probable that, for the early years, in particular, the counties of south-east England are exceptionally rich in the quantity and quality of maps produced. 1 In recent years, while most books on early maps make only passing reference to local work, two volumes of outstanding merit have been published.2 Both concern Essex in particular: the one studies John Walker, senior and junior, two men from the village of South Hanningfield, near Chelmsford, who, between 1579 and 1616, pro- 1 See for example the Catalogue of Maps in the Essex Record Office ( 1947) and Supplements, the Catalogue of Estate Maps in the Kent Archives Office ( I 973) and (Ed.) P. Eden, Dictionary of Surveyors (1975-6). 2 A. Edwards, The Walkers of Hanningfield (1983) and A. Stuart Mason, Esse., 011 the Map (1990). These are studies of map-makers rather than considerations of the value of maps for local history studies. It should also be noted that valuable research is being carried out at Exeter and Cambridge Universities, especially in relation to the making of maps and estate management. See also the article by Dr D. Fletcher on pp. 85-109 of this volume. 63 F. HULL duced maps of outstanding beauty and accuracy and who evolved what was apparently a unique method of depicting dwellings, both large and small;3 the other volume considers the local surveyors of the eighteenth century, the hey-day of local cartography, and is a model of its kind providing information about the manner in which skills were acquired and used and valuable insights into matters such as the association of the teaching of mathematics with the profession of surveyor. Moreover, the information thus brought together is not confined to Essex, but throws some light on developments in Kent and other counties. 4 In a much more modest fashion, this article attempts to do for Kent in the seventeenth century something of what Dr Stuart Mason has done for Essex in the eighteenth, but whereas his book is the result of many years of painstaking research, this paper is essentially a distillation of the present state of knowledge based principally upon the maps brought together at County Hall, Maidstone.5 In any study of this kind, however, it has to be recognized that the maps examined are survivals and that there is no means of knowing what has been lost over the years.6 For some surveyors many maps survive, for others a single example must suffice, a state of affairs peculiarly frustrating when one meets with an example of outstanding quality and yet has nothing with which to compare it, nor other information regarding the map-maker in question. The result is that for each man we can say something of his relative accuracy and artistic skill and, when there is a series of maps existing, something of his development over a period of years, but we cannot properly compare one surveyor with another except in very subjective terms. In addition, although in Kent, nearly one hundred practitioners appear to have been at work during the period 1590-1700, only a few have left information regarding their place of residence or work-base, still fewer give any evidence of their background or training. By the eighteenth century advertisements in local newspapers help to provide evidence of who and what local map-makers were, but at an earlier date it is far more 3 Edwards, op. cit., 81-90. 4 For each section of his book Dr Stuart Mason identifies surveyors from Kent, London and elsewhere giving such details regarding them as he knows. 5 Essentially the evidence examined is derived from the Catalogue of Estate Maps (1973) together with an MS. Supplement compiled by the writer before retirement in 1980, a list of transcripts held in the Centre for Kentish Studies, together with such other data as has come to the author's notice. 6 Dr R.J. Kain, of Exeter University, estimates that perhaps one map in twenty has survived, this estimate was reached on the basis of the analysis offered by Dr A.R.H. Baker, see Arch. Cant. lxxvii (1962), 177-84, and the conclusions in C.W. Chalklin, Seventeenth Century Kent (1965). 64 KENTISH MAP-MAKERS difficult and very few appear to have left wills or other direct evidence regarding themselves or their families. It has been said that although many early surveyors were held in low esteem because of their lack of skill and amateurism, 'others were lawyers and educated men ... and some landowners made their own maps as surveying came to be seen as a social accomplishment'. 7 At the same time there is good reason to link the scholastic profession with surveying. The seventeenth century saw the rapid growth of mathematical schools (the Sir Joseph Williamson's School at Rochester was one such), and these establishments taught surveying as part of the normal curriculum, usually addressed to training boys for service at sea. It is hardly surprising to find several early map-makers who claim to be mathematicians or even admit to an association with such a school. 8 Another important clue regarding surveyors is the clientele they served. In this regard, although Kent, as other counties, had its quota of landed gentry and nobility, it also had a remarkable number of corporate bodies with extensive landed interests. Thus not only have we many fine maps of gentleman's estates, in a unique sense, it is the maps and plans which were prepared for the capitular establishments of Canterbury and Rochester, for the Commissioners of Sewers and the Lords, Bailiff and Jurats of Romney Marsh, for Dover Harbour Board and the Wardens of Rochester Bridge which gave a special impetus to local map-making and left a particularly rich heritage. One result of this peculiarity is the evidence for continuing activity and possibly even for the development of early business houses at Canterbury and Rochester, while at Tonbridge, in particular, and many other large and small centres of population, there were local cartographers at work throughout the period under review. Whether, as today, the evidence for such a man in a village suggests an association with the nearest town is prol?lematic without further .knowledge. John Watts of Thurnham and Boxley does not appear to have worked from Maidstone, though William and Thomas Boycot of Fordwich ·certainly had links with Canterbury. Another factor in dealing with any county adjacent to London is the extent to which clients used the services of men based in the metropolis. In general, evidence suggests that this practice was less marked in Kent than in Essex, but it must always be borne in mind especially when con- 7 Dr A.S. Bendall, Emanuel College, Cambridge, who is preparing a revised edition of Peter Eden's, Dictionary of Surveyors. 8 See Stuart Mason, op. cit., 7-9, for a discussion of this aspect. 65 F. HULL sidering the north-western part of the county. 9 Even more significant would appear to be the link between Kent and Sussex and there is evidence of definite cross-fertilisation and difficulty in determining whether those active in the Weald came from the Kentish or Sussex side of the border. Although even a national figure such as Christopher Saxton might be found working on a Kentish estate, the great majority of these surveyors were local men though they might work for clients some miles from their place of domicile. 10 A further frustration arises with those who failed even to leave a name. A magnificent set of maps of Dover - town, castle and harbour - dating from the second half of the sixteenth century is to be found in the British Library, though facsimile copies are in the Centre for Kentish Studies, but we know nothing of who was responsible. Similarly fine maps of Hamptons in Brabourne and of the Downs behind Brook were prepared by an unknown hand about 1596. 11 Some of the truly Kentish surveyors were men of substance: William and Thomas Boycot of Fordwich served that town as jurats at the Cinque Ports assemblies;12 James Beecher, whose work was mainly in the eighteenth century, produced a map of his family estate between Sevenoaks Weald and Chiddingstone in 1699, likewise Abraham Walter of Larkfield, though in his case as part of the Twisden property. 13 In contrast, George Russell, a fine late seventeenth-century surveyor, was a master at the Williamson Mathematical School and, with the naval base at Chatham, it is hardly surprising to find those who termed themselves 'philomath' working in that neighbourhood. 14 If one considers the question of cartographic skill and artistic merit, one is dealing with some seventy individuals whose activities depended not only upon their own ability, but also on the wishes and depth of purse of their patrons and although, as already commented, we cannot properly compare one man with another, we can examine 9 The contention regarding Essex and Kent and the use of London surveyors appears in an article by the author in An Essex Tribute, Essays published in honour of F.G. Emmison on his 80th birthday (1988). 10 A good example was Robert Spillett of Tonbridge who worked for the Filmers of East Sutton some twenty miles away. 11 Catalogue of maps·in the British Museum (vol. I), 93-5, and Centre for Kentish Studies (CKS) (formerly the Kent Archives Office), DHB P141/1-6; and also UlSl Pl,2. 12 See, F. Hull, Calendar of the White and Black Books of the Cinque Ports (1966), 461-533. 13 CKS: Ul000/6 Pl and U49 P4. 14 See Catalogue of Estate Maps, p. ix. James Almond was termed 'philomath' and almost certainly came from Chatham. 66 KENTISH MAP-MAKERS the use of colour, scales, depiction of dwellings and artistic talent. Colour is usually utilised in one of three ways: (a) to distinguish land use - green for meadow and brown for arable being obvious choices; (b) to distinguish ownership - particularly important where maps were used as a basis for rating or other fiscal purpose; (c) simply for the embellishment of borders, cartouches and coats of arms. Scales varied widely based on the rod, pole or perch of five and a half yards and the chain of twenty-two yards and, although there is a clear relationship between the area to be mapped and the scale used, this is not an immutable rule and, on occasions, even the size of the sheet of parchment seems to determine the scale. In general terms, although there are many examples of maps drawn on the scale of 6 chains to one inch (13.3 inches to one mile) and even smaller scales, a large proportion of Kent maps were on scales larger than 3 chains to one inch (26.6 inches to one mile) and, of those examined, nearly a quarter were on a scale of two chains to one inch ( 40 inches to one mile). This fact undoubtedly related to the relatively small size of many Kentish farms and holdings and the smaller scales noted were often used for maps of waterings and the extensive marshlands administered by the Commissioners of Sewers and like bodies.15 The depiction of buildings presented the surveyor with many problems. The concept of the block plan of a dwelling-house belongs to the eighteenth century and, at an earlier date, an attempt was made to draw houses, churches and other buildings as they appeared on the ground. Usually the principal house and other major buildings, especially churches, were drawn with considerable accuracy, though whether smaller or ancillary properties such as barns, sheds, etc., were so depicted is less certain. Sometimes the surveyor made little or no attempt to distinguish one building from another. A map by William Boycot, of Sandwich in 1615, shows the town totally congested with dwellings, but, apart from the three churches, there is no attempt at accuracy of drawing and a similar standardisation occurs in Thomas Norton's map of Cobham in 1641.16 The methods used varied: a house might be drawn in simple elevation with one side only being shown, or in perspective from an angle so that two sides were visible, or, in some special cases in 'bird's eye view'. Here the surveyor looked down on the house from a particular direction and the outcome differed markedly according to the direction of the survey. It might show the front or back of the 15 See CKS: S/Rm Pl-6 and SINK Pl-6 for the use of smaller scales. 16 CKS: U562 Pl and U565 Pl. 67 F. HULL building together with the roof structure, or it might only show the gable end and a very limited amount of roof. An exceptionally fine map of the city of Canterbury and the ar,chiepiscopal estates adjacent, drawn by an unknown hand about 1600, reveals how successful this method of depiction could be, but no case in Kent, to the author's knowledge, uses the remarkable method developed by the Walkers of Essex by which the surveyor was able to show each side of a courtyard as well as the roof of the building. 17 The drawing of houses, especially those of major significance, has a special archaeological merit for so often the early building has been radically altered or demolished and these drawings, even though no bigger than a postage-stamp, may provide the only clear evidence of what was once in existence: a good example appears on a map of Combwell in Goudhurst of 1621. 18 Later in the century it became common for the main property to be enlarged, either on the map itself or within an inset. This gave the cartographer a considerable opportunity to reveal his skills of draughtsmanship or, on the contrary, to display his idiosyncracy of style, and while Richard Browne roduced a splendid drawing of Stanham Farm in Dartford in 1658, 1 one, William Tampon, of whom nothing is known, when surveying the Leeds Castle estate in 1649, showed a castle in the centre of his map which has more in common with the fantasies of Ludwig II of Bavaria than with the actual edifice at Leeds.20 Finally, there is decoration. For many this consisted of little more than a colourful border, while for others elaborate cartouches with designs similar to the architectural and furniture patterns of the period were imperative. By the 1620s the addition of the coat of arms of the patron was not uncommon, though heraldic accuracy was not apparently essential provided that the client claimed to be armigerous. Occasionally livestock might appear on the meadows or pastures and ships might sail on the sea. Mathew Poker, when drawing a fine map of Romney Marsh in 1617, embellished his work with a whole fleet of vessels in Romney Bay, and George Russell, one of the most accurate of late seventeenth-century surveyors, drew a magnificent ship on his plan of Chalk and Denton Level in 1694.21 17 Cathedral Archives, Canterbury. The Walkers of Essex used a base line in the correct orientation and drew an elevation on that line, if a dwelling was built round a courtyard each elevation could thus be shown the building appearing to lie flat rather like an open flower. In Kent the simple elevation or perspective view was preferred. See Edwards, op. cit. 18 CKS: U814 Pl. 19 CKS: U417 Pl. 20 CKS: U825 P6. 21 CKS:U1823 P2 and SINK P3. 68 KENTISH MAP-MAKERS Generally, relief is missing, for the surveying instruments of the day did not allow for the measuring of heights and the needs of the client seldom required evidence of hills. Occasionally, however, and more as a decorative feature than exact evidence, hills might be shown pictorially, a good example occurring on a map prepared for the Commissioners of the Rother Levels in 1633, a map which also shows the surveyor with his instruments.22 The importance of the perch and chain has already been mentioned. The chain in particular became significant after the work of Gunter in the early part of the century and the establishment of the standard chain of 22 yards and 100 links. Moreover, the chain provided the all important ratio of one chain to one inch being eighty inches to one mile. The principal surveying instruments at this period were the plane-table and an early theodolite, which because of its greater flexibility in use quickly superseded the more cumbersome and less accurate plane-table. 23 In the list and detail of surveyors which follows, the county has been divided arbitrarily into seven regions: Canterbury and northeast Kent; the Maidstone and mid-Kent area; Rochester and the Medway with north Kent; north-west Kent; south-east Kent and Romney Marsh; the Tonbridge area; and the Weald and Sussex border. In each case those surveyors for whom there is evidence of domicile come first, followed by those who worked mainly in that area but for whom other evidence is lacking. Canterbury and north-east Kent No centre within the county provides more evidence of continuing activity than Canterbury. This is understandable when one considers the medieval significance of the city and that maps were drawn for the purposes of the monastic houses there from the middle of the twelth century.24 For the period here being examined the earliest example is probably a map of St. Paul's parish dated between 1560 and 1580, but it is anonymous, as is also a splendid map of the whole city and the archiepiscopal estates adjacent dating from c. 1600. On the other hand a certain Thomas Langdon produced a fine plan of the Black 22 CKS: S/Ro Pl. 23 For further details of surveying practice see C.R. Crone, Maps and Map Makers (1965); Stuart Mason, op. cit., 15-18, and Catalogue of Maps in the Essex Record Office (1947), pp. vii-ix. 24 See (Eds.) Skelton and Harvey, Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (1986), 43-58. 69 F. HULL Friars estate in 1595, but this is only known from a later copy.25 From the early years of the seventeenth century, however, there is strong evidence suggesting that a school of surveyors was at work in the city, or, at least, that one might postulate a business house and this evidence begins with the family of Boycot of Fordwich. William Boycot (ft. 1615-48), appears as a man of substance living at Fordwich and going as one of the jurats of that town to the Cinque Ports Guestlings of 1634, 1641 and 1647.26 He was a prolific cartographer of considerable skill with a distinctive use of blue and yellow, especially in his borders and for other decoration and also of a fine red pigment (similar to that used by Walker of Essex), for his autograph and other writing. He worked widely but mainly in the east of the county, thoufh producing a map of Halling for the bishop of Rochester in 1634. 7 Among the lay patrons who used his talents were the Darells of Calehill and the Bouveries of Folkestone. One of his most distinctive and interesting maps is that for the manor of Horton in Chartham, 1633, which was the basis for an article published in 1982.28 William Boycot may have been associated with north Wales for there is evidence of his work in Denbigh and Flint.29 More than twenty of his maps are known to survive and as a group they form one of the finest Kentish expressions of cartography for the years before the Interregnum. William was followed by Thomas Boycot (ft. 1652-78), possibly his son, who certainly continued the association with both Canterbury and Fordwich. He, too, was a jurat, attending the Guestlings of 1668, 1669, 1670, and 1674. Indeed, in 1670 he was mayor of his town.30 The similarity of style with William is obvious, but Thomas tends to be somewhat bolder and less delicate than the older Boycot, though he is no less accurate. He also favoured the use of blue and yellow borders and used the red pigment. He worked extensively in Romney Marsh and carried out a series of surveys for the Lords, Bailiff and Jurats, including maps with detailed drawings of New Romney and Dymchurch as they were in the mid-seventeenth century.31 An exception to his usual style is a somewhat damaged map of Scotts Hall in Smeeth, 1656, where he not only included the Scott coat of 25 These three maps are in the Cathedral Archives, Canterbury. 26 Calendar of White and Black Books (1966), 461-82. 27 CKS: U47 PSS. 28 CKS: U386 P2. See, T. Tatton-Brown, 'The topography and buildings of Horton Manor near Canterbury'. Arch. Cant., xcviii (1982), 97. 29 See, Eden, Dictionary of Surveyors. 3° Calendar of White and Black Books, pp. 521-33. 31 CKS: S/Rm Pl,2. 70 KENTISH MAP-MAKERS arms, but also drew various beasts grazing in the park, 32 the result being altogether less finely drawn than is usual with him. He, like William, also worked for Darell of Calehill. It appears that the business established by the Boycots passed to the Hill family of Canterbury after 1678 and there is evidence that Thomas Hill and his brother Francis were based in St. Paul's parish within the city. Thomas (ft. 1677-89), not only has left many fine maps, but, presumably because of his beautiful writing, was responsible for keeping the parish register of that parish. 33 Certainly the family of Hill produced some remarkable surveyors, Francis, the brother of Thomas worked mainly in the eighteenth century and left some exceptionally beautiful examples and may have started a school of surveyors, and the son, Jared, not only mapped the capitular estates but is known for his work elsewhere in Kent, in Essex, Suffolk and Sussex. 34 Thomas the founder of the line was a most distinguished surveyor, producing maps of great clarity and beauty with fine cartouches and other decoration. He appears to use some cartouches which were similar to, or derived from, those used by Thomas Boycot and, at times, his work can become overburdened with decoration. A particular example of this feature is his map of Nick Hall in Chartham, 1684, in which the actual fine perspective drawing of the house is submerged in a vast cartouche of grotesque birds and in which the foliage of the trees is uniformly bisected so that the leaves appear green and yellow at the same time, giving a most distinctive effect, even if a somewhat curious one. 35 Thomas Hill worked for the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury producing a map of the precincts showing the system of waterworks, between 1674 and 1681; and also mapped their London estates. 36 He also worked for the Commissioners for the Rother Levels which brought him into Sussex.37 Two other surveyors associated with Canterbury at this period were Thomas Boorne, who prepared maps of Canterbury in 1689 and of Seasalter for Jervis Dodd in 1693, and, one, M. Delahaye, who worked at Dover in 1631.38 Nothing is known of either man. Simon 32 CKS: U274 Pl. 33 I am indebted to Miss A.M. Oakley, of the Cathedral Archives, for this information and for much of what follows regarding the Hill family. 34 See, Catalogue of Estate Maps (1973), A. Stuart Mason, op. cit., and Eden, op. cit. 35 CKS: U120 P7. 36 These maps are in the Cathedral Archives, Canterbury. 37 CKS: S/Ro P2. 38 CKS: U442 and TR 2010/1. 71 F. HULL Barrow of Ash-next-Wingham is known for maps of Eastry, Winf ham and Canterbury drawn in 1625, 1650 and 1653, respectively. 9 There are also seven other surveyors who worked in this part of Kent, but whose domicile is unknown, each of them being represented by one map only. These are John Bedo, Eastry 1668, Joseph Castell, surveyor, Reculver, c. 1650, R. Flatman, Littlebourne and Wickhambreaux, 1695, Joseph Juli, surveyor, Chilham and Chartham, 1695, C. Passmore, Canterbury, 1686, James Tonbridge, land measurer, Ospringe, 1645, and Thomas Wrake, Kingston, 1679.40 Of these the most noteworthy is Thomas Wrake who, by reason of his style and use of colour, appears to show an affinity both with Thomas Boycot and Thomas Hill so that one wonders whether he, too, was a member of the group of surveyors based in Canterbury or, at least, was apprenticed to them. Maidstone and central Kent In contrast to Canterbury, Maidstone does not appear to have had a 'school of surveyors' in the early period. Only one man is known to have come from the town, Samuel Pierse, who produced a fine map of Godinton in Great Chart in 1621.41 He may, perhaps, be related to Marke Pierse of Sandhurst (see below), but there is no direct evidence for this. We do know, however, that he worked in Essex and Northants. and possibly in Yorkshire between 1614 and 1621.42 A better known cartographer and one of the most fecund was Abraham Walter of Larkfield (.ft. 1681-1700), who lived in the fine timber-framed house, now 'the Wealden Restaurant' situated on the south side of Larkfield Cross.43 Being resident on the Twisden estate, it is understandable that he mapped their lands in East Malling and neighbouring parishes during the years 1681-85. In the 1690s, he followed the steps of William Boycot and re-surveyed the Bouverie estates at Folkestone.44 Walter's maps have a certain attractiveness though their accuracy is sometimes suspect, but his decorative skill was peculiar and somewhat crude. He favoured geometrical shapes or pen and ink scrolls with grotesque cherubs' heads, occasionally even cutting a cartouche from what was presumably a pattern book 39 CKS: U373 PI, U1854 Pl and the Cathedral Archives. 4° CKS: U854 P2, U1823 PS, U47/55 P26, TR 453/1, the map by Passmore is in the Cathedral Archives. 41 CKS: U967 Pl. 42 Eden, op. cit., and Essex Record Office, D/DL Pl. 43 CKS: U49 P4/l. 44 CKS: TR 270/1-10. 72 PLATE I ,c-,<:, ,-=1 ,.,..;> • Lnpo O,;mi-n,,16).:, · ,,s;:y,<,;:;J WILLIAM BOYCOT,ft. 1615--48. Grove Manor in Woodnesborough and Worth, 1635. A typical example of Boycot's work, showing his method of depicting buildings, including Woodnesborough church, and also his use of blue and yellow for decoration and red pigment for his autograph (See pp. 70-1). PLATE II THOMAS HILL, sworn surveyor, JI. 1677-89. Woodbrooke Farm and Lower Otame Farm in Warehorne and Walland Marsh. 1687. A beautiful example of Hill's skill as a cartographer. Note the drawings of Brooke House, Midley chapel (now a ruin) and Lydd. Note, too. the use of gold leaf in the decoration (See p. 71). PLATE Ill GEORGE RUSSELL,fi. 1680-1718. Chalk and Denton Level, 1694. Two extracts from this finely executed map of part of the north Kent marshes. The centre of the map, including a fine drawing of a vessel on the Thames and also the compass-rose. (see also Plate IV, p. 80). PLATE V JOHN PA TTENDEN ,ff. 1639-60. Property in Stone-in-Oxney, 1660. Patttenden's simple but clear style is well shown in this example. with buildings in elevation. Pattenden also distinguishes upland and marshland on this map (See p. 79). KENTISH MAP-MAKERS and sticking it onto his map. He then tended to cover the whole with yellow ochre or a mixture of yellow and black, but taking little care to keep within lines. The result can be quite effective from a distance, even if crude, but it hardly inspires confidence in the degree of care taken over the map itself. Nevertheless, Walter c1:emains one of the principal surveyors of the late seventeenth century and well over thirty of his maps survive. Another significant cartographer was John Watts of Thurnham and Boxley (ft. 1692-1719), who worked for the Cage family of Milgate, Bearsted.45 Although only represented by one work before 1700, it is worth noting that in 1709 he produced a fine map of Thurnham, for which he used a grid to simplify identification, hill-shading to emphasize the scarp slope of the North Downs, decorating his map with the arms of Cage and an 'armageddon' as a cartouche. He also embellished the whole with lengthy historical notes.46 Three other map-makers have left single examples of their work. John Hine prepared a splendid map of Wrotham in 1621, of special interest in that it reveals a vestigial open-field at the foot of the Downs ( the same field is also shown on one of the maps by Abraham Walter); William Tampon mapped Leeds Castle estate in 1649 for Sir Cheney Culpeper and not only drew a crude and totally inaccurate castle, but also crossed his map with lines linking four compass-roses at the margins of the map, the result adding confusion to an otherwise colourful and interesting survey of the estate before the present lakes were created; and Thomas Fisher drew a plan of land at Linton for John Beale in 1653.47 Rochester and the Medway with north Kent Probably the earliest identifiable map-maker in this article was John Woode, who drew a map of the Hundred of Milton in 1575 and referred to himself as 'receyver to Mr. Thomas Randolf, esq.', lord and steward of the hundred.48 Of much greater significance, however, is the fact that Rochester was the base from which Philip Symonson (ft. c. 1550-1598), worked. Symonson is best known for his fine printed map of Kent, which, while based on that of Saxton, improved upon it. As a local surveyor, Symonson was most active on behalf of the Wardens of Rochester Bridge and his maps of the Bridge estates are a model of clarity and cartographic simplicity with 45 CKS: U1258 Pl. 46 CKS: USSS Pl. 47 CKS: U681 P31, US25 P6 and U24 PIO. 48 CKS: U2089 Ml. 73 F. HULL little decoration. 49 It would be interesting to know more of the Symonson family. Thomas Symonson was headmaster of Maidstone Grammar School in 158550 and, another, Edward Symonson was a map-maker of some quality, who drew a fine map of Wouldham for John Marsham in 1634. 51 Later in the century three mathematicians were active: Richard Burley, who also worked for John Marsham at Birling in 1652 and who styled himself 'Reader in Mathematics at Chatham'; James Almond, 'philomath' (ft. 1668-1700), who also appears to be from Chatham and who worked for the Dean and Chapter of Rochester, the Trustees of Chatham Chest, the Wardens of Rochester Bridge and, in Sussex, for the Commissioners of Sewers; and, finally, George Russell, master at the Sir Joseph Williamson's Mathematical School (ft. 1680-1718).52 Russell was one of the finest of all these surveyors. Apart from compass-roses and an occasional object such as a vessel on the Thames, he eschewed decoration, but he produced clear and beautiful maps both functional and accurate. He worked extensively for the Commissioners of Sewers in north Kent, mapping with great care the marshes from Gravesend to Grain. During his long career he also worked for the Wardens of Rochester Bridge and the Trustees of Chatham Chest and is also known to have mapped property in Essex. 53 Less well known surveyors include Robert Fe/gate of Gravesend, who is only recorded by maps of Aldham and Great Wigborough in Essex in 1675, but who, in the former case was another employed by Sir John Marsham.54 Firther Fircher prepared a map of Halling, also for Marsham, in 1660, and Thomas Norton a map of the Cobham Hall estate for the Duke of Lennox in 1641.55 A map of the Medway estuary complete with the English fleet at anchor, was produced by a Robert Seath in 1633. The original of this map is in Alnwick Castle, and it may be that Seath was a surveyor to the Duke of Northumberland and had no other Kentish associations. 56 North-west Kent No part of the county is more difficult to examine than the outerLondon area. In part this is because none of the surveyors noted 49 The originals are in the archives of Rochester Bridge. 50 See, Maidstone Grammar School, a record (1965), 6. 51 CKS: U1515 PIO. 52 CKS: U1515 P3, U1193 Pl, CCRc P5, 62 and SINK Pl-6. 53 Eden, op. cit. 54 Essex Record Office D/DWe P2 and D/DQa 2. 55 CKS: U1515 P12 and U565 Pl. 56 CKS: TR 583/1. 74 KENTISH MAP-MAKERS admits to living anywhere in this part of Kent and, in part, because of the proximity of London and the likelihood that patrons in the area with close association with the capital would hire Londoners to carry out their desires. The first of the group who were active in this area is Nicholas Lane (ft. 1618-42). He prepared maps for the Lennard family of West Wickham about 1632 and has also left a map of land at Brenchley. Lane is a well known surveyor, probably from London, who is known to have worked in Essex, Surrey, Sussex, Middlesex, Cambridgeshire and Northants. 57 In contrast Richard Browne (ft. 1658-90), was almost certainly Kentish. He is not recorded outside this county and is known for a map of Stanham Farm at Dartford in 1658, of special interest partly because he did a fine enlarged drawing of the farmhouse itself, and partly because the area shown is now almost obliterated by railway lines to the west of Dartford station. He is also known for maps of properties at Cudham, Chevening, Brasted and Penshurst, West Wickham, Hastingleigh and Wittersham. Among his patrons were the Lennard family and the Commissioners for the Rother Levels.58 Another surveyor who found favour with the Lennard family of West Wickham was John Aldgate 'welwiller unto the Mathematicks'. Two of his maps survive from 1659, both of the West Wickham estate, but neither is distinguished in style. 59 One, William Mar, drew a map of Foots and North Cray in 1683, which includes a fine drawing of Pille Place and of the church. Mar is also known to have worked in Surrey and Oxfordshire, but there is some uncertainty as to whether this is the same man as the William Marr who was active in London, Middlesex and Surrey, between 1640 and 1685, and who was both Parliamentary Surveyor of Crown Lands and, later, clerk to the Kitchen for Charles II. 60 Another puzzle concerns the last of this group, John Brasier, surveyor, who drew a map of Cudham for the Earl of Sussex in 1699. This is apparently the only reference to John, but William Brasier, possibly his son, was a well known cartographer in the next century, and one who, perhaps, began his career in Kent with a map of Godmersham in 1720. The question remains, were John and William related and did they come from Kent or London?61 57 CKS: U312 PI, U908 P78 and see also Eden, op. cit. 58 CKS: U417 Pl, U908 P76, S/Ro P3. 59 CKS: U312 P2,3. 6° CKS: Ul823 P4 and see Eden op. cit. 61 CKS: Ul616 Pl. William Brasier is best known as surveyor to the Duke of Montagu from 1734, but his earliest map of Godmersham suggests that he had Kentish connections. John Brasier also prepared a plan of Chevening Warren in 1704. 75 F. HULL South-east Kent The problem in this area of the county is that we can identify the patrons better than the surveyors for there were essentially three great clients for cartographic skills - the Bouveries of Folkestone, Dover Harbour and the Lords, Bailiff and Jurats of Romney Marsh. The first of these we may pass over for already it has been noted that William Boycot and Abraham Walter each surveyed the Bouverie properties. So far as Dover Harbour Board is concerned the great series of anonymous maps for the sixteenth century has also been noted, but in 1641 a certain William Eldred prepared a magnificent detailed survey of Dover, including the town, harbour and castle. Each street was mapped independently, giving the names of the owners and occupiers of the dwellings depicted. This work of Eldred's forms a most detailed and important study of the town and port at that time and it is doubly sad that we know nothing of Eldred, himself. He was not a freeman of Dover and there is no clue as to his domicile. 62 The earliest survey of the Romney Marsh area appears to be a splendid map by Mathew Poker, 1617.63 The original was found among the Papillon archives at Acrise, which might suggest a link with the Lords of the Marsh, but there is no evidence to suggest that they commissioned the work and, in any event, the map covers the whole marshland area from Rye to Hythe, which means that it has more in common with the county maps of the period than with the majority of estate plans. Poker shows towns and villages, the course of the Rother at that time, the hills to the north of the marsh pictorially and a whole armada of little ships in Romney Bay. As a map of a whole geographical area this work is outstanding, and it seems incredible that such a fine example of cartography should be the sole surviving work of a man of whom we know nothing. That this man was appreciated at the time is evident by the fact that there was a printed version published, another similarity with the county maps of the period. It was not until 1652 that the Lords, Bailiff and Jurats decided to have the lands under their control properly surveyed for cadastral purposes. At the Grand Lath held on 10 June of that year, it was ordered 'that a generall admeasurement of the whole Marsh be hadd between this and the next generall Lath', and it was also ordered that contracts should be entered into with four 'able Land Measurers'. 64 62 CKS: TR 1380. 63 CKS: U1823 P2. See also Arch. Cant., xxx (1914), 219-24. 64 CKS: S/Rm S02. 76 KENTISH MAP-MAKERS A year later it was reported that Mr Boycot, Mr Beale and Mr Ramsden, land measurers, had brought in their maps and payment to them was ordered, half immediately and the other half at Michaelmas 1653.65 It has already been noted that Thomas Boycot worked for the Lords, but Thomas Ramsden represents the one family of surveyors which we know was resident in the vicinity. In 1637, George Ramsden drew a map of Woodchurch glebe, known only from a nineteenthcentury copy. He, himself, was from Woodchurch and it is likely that Thomas Ramsden, who worked for the Grand Lath, also came from that village. His maps were crude and uncoloured with little artistic merit, but he must have had some reputation as a surveyor in that neighbourhood. 66 A fine cartographer whose domicile is uncertain was Ambrose Cogger, known for maps of Appledore which he made for Edward Chute in 1628 and also of Old Park, Goudhurst, made the same year for the Roberts family of Glassenbury. 67 Cogger is a well attested name in Kent, but there is no definite association with a particular parish. John Beale, another of the three employed by the Lords of the Marsh in 1652, produced maps of lvychurch and Brenzett, Stone-inOxney and Biddenden between 1652 and 1666. His work, like that of Ramsden, is somewhat amateurish and crude and he worked with Thomas Ward for the map of Stone in 1665. Ward is otherwise unknown, as is Robert Rogers for whom a fragment of a map of Lympne, 1640, survives. 68 The Tonbridge area Among the earliest of Kentish surveyors was Henry Allinn (Allen) (ft. 1599-1619). 69 He was particularly active in the Lamberhurst district producing carefully drawn maps with compass indication in the borders rather than by a compass-rose and generally eschewing decoration. He uniformly seems to have used a sepia pigment or ink and no other colouring. An Elias Allen is also recorded as having been born in Kent and dying in 1654. He is known by a copy of a map 65 CKS: ibid. In all Ramsden was paid £15, Beale £29 13s. 4d. and Boycot £44. 66 CKS: S/Rm Pl/5,7,8 and also U78 P38 and U1506 Pl/41. It should also be noted that other maps of marshland estates remain in private hands and are not included here. 67 CKS: Q/Z Pl. The Goudhurst map was added to in 1680 by Abraham Stringer, a man otherwise unrecorded. 68 CKS: U24 P26, U409 P19, S/Rm Pl/1, 2/2,3. 69 CKS: U806 P3, U840 P6,7. 77 F. HULL of Faversham, c. 1650, and by work in Berkshire, Surrey, Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire. 70 Another Tonbridge map-maker was Anthony Denton (ft. 1630-42), who left a map of Goudhurst, 1637, but is better known for work in Warwickshire.71 More significant for Kent was Robert Spillett (ft. 1683-97), who, although resident in Tonbridge, is best known for his extensive work for Sir Robert Filmer of East Sutton. 72 He produced at least six maps for the Filmer estate, simple and attractive in style, but in no way outstanding. A much more distinguished cartographer was James Beecher. At various times he lived at Edenbridge, Chiddingstone and Tonbridge and worked zealously for the Streatfeild family. In 1699, however, he mapped Retherden Lands in Chiddingstone and Sevenoaks Weald, which he recorded as 'belonging now to James Beecher which was left him by his father James Beecher heretofore purchased of the Beechers by his grandfather James Beecher of Hale not far distant'. Beecher's work is always beautifully presented and, in 1702, he drew a map of 'the mansion house of Henry Streatfeild, esq., called High Street' and embellished it with a fine large-scale drawing of the house and gardens which were obscured when Chiddingstone Castle was built in the last century. 73 There are two unknown surveyors who worked near Tonbridge, one, who refers to himself as 'G.B.', drew a map of Panthurst Park for Thomas Lambarde in 1630 and decorated it with a fine border and with many beasts in the park itself; and George Bache/er, who, in 1613, prepared a splendid map of the earlier house and gardens at Chevening for the Lennard family. Bacheler is also known to have been active in Sussex.74 The Weald and the Sussex border Inevitably the area covering the Sussex border raises problems of residence and for many it is impossible to say whether they were Kentish or Sussex surveyors. The earliest of the group, in fact, was from Sussex and was buried at Eastbourne, but he was one of the most distinguished and distinctive of our early local cartographers. John de Ward (ft. 1618-25), is known in Kent for three maps drawn between 1621 and 1622, two for the Campion family of Combwell in 7° CKS: TR 1630/1, see also Eden op. cit. 71 CKS: U363 Pl, see also Eden op. cit. 72 CKS: U120 PlO, 16, 27, 28, 47. 73 CKS: Ul000/6 Pl and also see U908 for other examples of Beecher's work. 74 CKS: U442 P102 and TR 1534/1. 78 KENTISH MAP-MAKERS Goudhurst and one drawn for the Bartholomews of Oxenhoath in West Peckham.75 De Ward's style was clear and bold with beautiful lettering and the principal houses of the estates were well depicted, though the map of Oxenhoath is much faded. The drawing of Combwell Priory, however, shows a fine Elizabethan mansion, now demolished, and is therefore of some special archaeological value. In 1622, also, one Marke Pierse of Sandhurst drew a fine map of Milkhouse in Cranbrook.76 He may have been related to Samuel Pierse of Maidstone and is a well attested surveyor over the first third of the century with work in Essex, Hertfordshire, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire. His client in Kent was Thomas Plummer who held a large and diverse estate in many Wealden parishes as well as on Romney Marsh and at Seasalter. Some 41 of these pieces of land, small and large, were mapped for Plummer by John Pattenden of Brenchley and Lamberhurst during the 1640s and later were bound together in a volume, which also included Marke Pierse's map.77 Pattenden was active between 1639 and 1660 and was prolific, over fifty of his maps survive. He was clear, bright and simple in style, his houses are usually in elevation, but his standard of decoration was less competent. Nevertheless, as a surveyor of the times of civil strife and the Interregnum, he is outstanding and his work is unmistakeable. He is essentially the map-maker of the Weald and few of his maps are for places outside that area and Romney Marsh. Later in the century, a certain Thomas Hogben prepared maps of property at Lenham in 1694 and Ashford in 1699, the latter for Sackville Tufton. 78 The Dictionary of Surveyors gives his dates as 1699-1727, but he was certainly active before 1699 and there is no certain evidence of his work during the eighteenth century. Another Thomas Hogben, probably his son, had a very distinguished career between 1720 and 1770 and was, himself, succeeded by his son, Henry, so that there is evidence of an important family grouping over more than a hundred years. The first Thomas Hogben produced clear and attractive maps with good cartouches, which suggest some link with the Hills of Canterbury. 79 If this is indeed so, then one could follow a single strand from the early seventeenth century through to the very end of the period of local surveying in the mid-nineteenth century. At much the same time as the first Hogben was active, the 75 CKS: U31 P3 and U814 Pl,2. 76 CKS: U1506 Pl/44. 77 CKS: U1506 Pl/1-43. 78 CKS: U1095 P13 and U2315 P4. 79 See, Eden op. cit., the second Thomas was schoolmaster at the Free School, Smarden, another link with education. 79 F. HULL PLATE IV Chalk and Denton Level. 1694. The main heading illustrating Russell's quality as a cartographer (Seep. 74). Trustees of Cranbrook School began to have their lands surveyed and used the services of Joseph Duke of Cranbrook in 1696 for a map of lands at Horsmonden, but that is the only known example of his work.80 The cartographers at work in the Weald whose domicile is unknown include W. Rowley, who, in 1626, prepared a map for Sir Edward Dering of the Surrenden estate in Pluckley. Once again one is surprised that such a fine map-maker should be represented by a single map. The Dictionary of Surveyors refers to him as being active 80 CKS: U280 P4. 80 KENTISH MAP-MAKERS between 1618 and 1627, but gives no further evidence.81 It should be noted, however, that there is a very fine anonymous map of Canterbury in the Cathedral Archives, undated, but ante 1640, which by reason of its bold, even if somewhat crude, use of colour and other features bears a distinct resemblance to the map of Surrenden. Whether it is by Rowley is unknown, but there is reason for suggesting that, and since the Surrenden map, also, would be anonymous, but for an endorsement in the hand of Sir Edward the possible link may be stronger. The Canterbury map has a special significance in that it shows the city within the walls just before it was taken over by the Parliamentarians and the walls were breached. Another exceptionally fine practitioner was Henry Couchman, but again only a single example of his work survives, a map of Goddards Green, Cranbrook, in 1636, drawn for Sir Thomas Hendle. 82 This map is outstanding in two respects, the splendid drawing of the timber-framed house and the very neat and colourful compass-rose. Henry Bigg (ft. 1637-40) worked for the Earl of Thanet and, in particular prepared clear maps of the woodland on the Hothfield estate. He is also known to have worked in Sussex; and Gulielmus Beng (ft. 1660-84), also worked in both counties and is represented in Kent by a magnificent map of over 1,000 acres in Horsmonden, 1675, on a scale of 26.6 inches to one mile, and also by a map of Eynsford, 1684.83 Other surveyors of the late seventeenth century were Henry Courthope, jun., who prepared a map of property in Hawkhurst for Peter Courthope in 1681 and who also worked at Biddenden in 1689; and George Ridgeway who worked at Hawkhurst in 1669 and at Wittersham in 1675, in the first case together with Richard Leader.84 Finally, there are six cartographers whose position in respect of the county of Kent is ambiguous or who were from some distance away. One of these is Gulielmus Ham, who styled himself 'curator' and who acted for the Hawkins family and left maps of their lands in Boughton in the Blean, Hernhill and Nor Marsh, Gillingham, all in the year 1665.85 Ham may have been a Londoner and associated with John 81 CKS: U275 Pl. This map has been mutilated at some time and one edge is missing. 82 CKS: U814 PS. It is worthy of note that another map of this property by Thomas Budgen in 1781 (CKS: U814 P9), shows the house with a plain stone face typical of the eighteenth century and not one of the fine timber-framed house which still exists. 83 CKS: U1095 P3 and U180 Pl. Bigg's maps are very difficult to identify since they are drawn as separate pieces of woodland. 84 CKS: U814 P13, U78 P6 and P24. 85 CKS: U47 P5,6. The map of Nor Marsh is, wrongly, attributed to Grain; it is, in fact, part of the hamlet of Grange in Gillingham. See also Stuart Mason, op. cit .. 6-7, 36-7. 81 F. HULL Ham, who taught in a school for boys intending to go to sea and was active in Essex in the early eighteenth century. A surveyor from Lincolnshire, Marke La Pla, worked for the Commissioners for Sewers for the Rother Levels in 1689 and referred to himself as 'a very able Engineer' -his map hardly supports the contention.86 John More of Farnham, Surrey, prepared maps of Ospringe and Lamberburst in 1599 and he is also known to have worked in Dorset, Hampshire, Sussex and Surrey between 1599 and 1617. The Kentish examples are far from outstanding cartographically and the Ospringe map, in particular, shows faulty orientation.87 G. Neighbour, who drew a plan of lands in New Romney in 1614, called himself 'general surveyor' and came from Oxford as surveyor for Magdalen College.88 It is somewhat surprising that while a number of Kentish surveyors worked in Essex, very few Essex men ventured across the Thames. One who did was Thomas Peachye of Romford, who was mapping at Dartford in 1617. 89 Lastly, there is Christopher Saxton, himself, who seems to have come into the county in 1590 and worked at Faversham and Sittingbourne. Neither map is exceptional, though each is fairly typical for the period in terms of both cartography and decoration.90 But this leaves an unanswered question -did master surveyors always carry out the work themselves or was it delegated to apprentices and accepted by the great man? Certainly, on occasions, maps were named for two persons, and this has occurred twice in the above list but there is no indication in either case whether one man was senior to the other. It is plain that more than one man was needed to carry out a survey, and Stuart Mason cites examples in Essex in the following century so that it seems wise to consider that Saxton's mas could have been the work of his pupils rather than the man himself. 1 It has been stressed throughout that these maps are survivals; there is no way of telling what has been lost, nor, indeed of confirming how many other surveyors there were at work during the century. We know of at least twenty anonymous maps for the period in question so that those whose names are listed are by no means the full number active and there is no reason to attribute any of the anonymous maps to any of the named surveyors, except perhaps in the case of Rowley. 86 CKS: U455 P4. 87 CKS: U471 Pl. Eden suggests Faversham not Farnham, but the maps in the CKS are quite clear in this respect. 88 CKS: Ul823 P84, a nineteenth-century copy. 89 CKS: U2087 Pl. 9° CKS: U390 P2 and TR 1411/1. 91 See Stuart Mason, op. cit., pp. 15-18. The examples cited are CKS: U78 P6 and U409 P19. 82 KENTISH MAP-MAKERS Additional maps and fresh names, together with odd snippets of information come to light from time to time, though it is probable that after nearly sixty years of archive work in Kent the majority of surviving maps is known and therefore the majority of the mapmakers, too. None the less these people represent a band of distinguished craftsmen of whose lives and characters, alas, all too little is known. Teachers and mathematicians, architects and carpenters, gentlemen following a whim, for whatever reason, they expressed themselves by their careful workmanship and their artistry and have left a legacy valuable to the local historian and geographer and a joy to the casual observer. 83