Parallels for the Roman lead sealing from Smyrna found at Ickham, Kent

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

Old Romney: An examination of the evidence for a lost Saxo-Norman port

A Bronze Age burial from St. Margaret's-at-Cliffe

Parallels for the Roman lead sealing from Smyrna found at Ickham, Kent

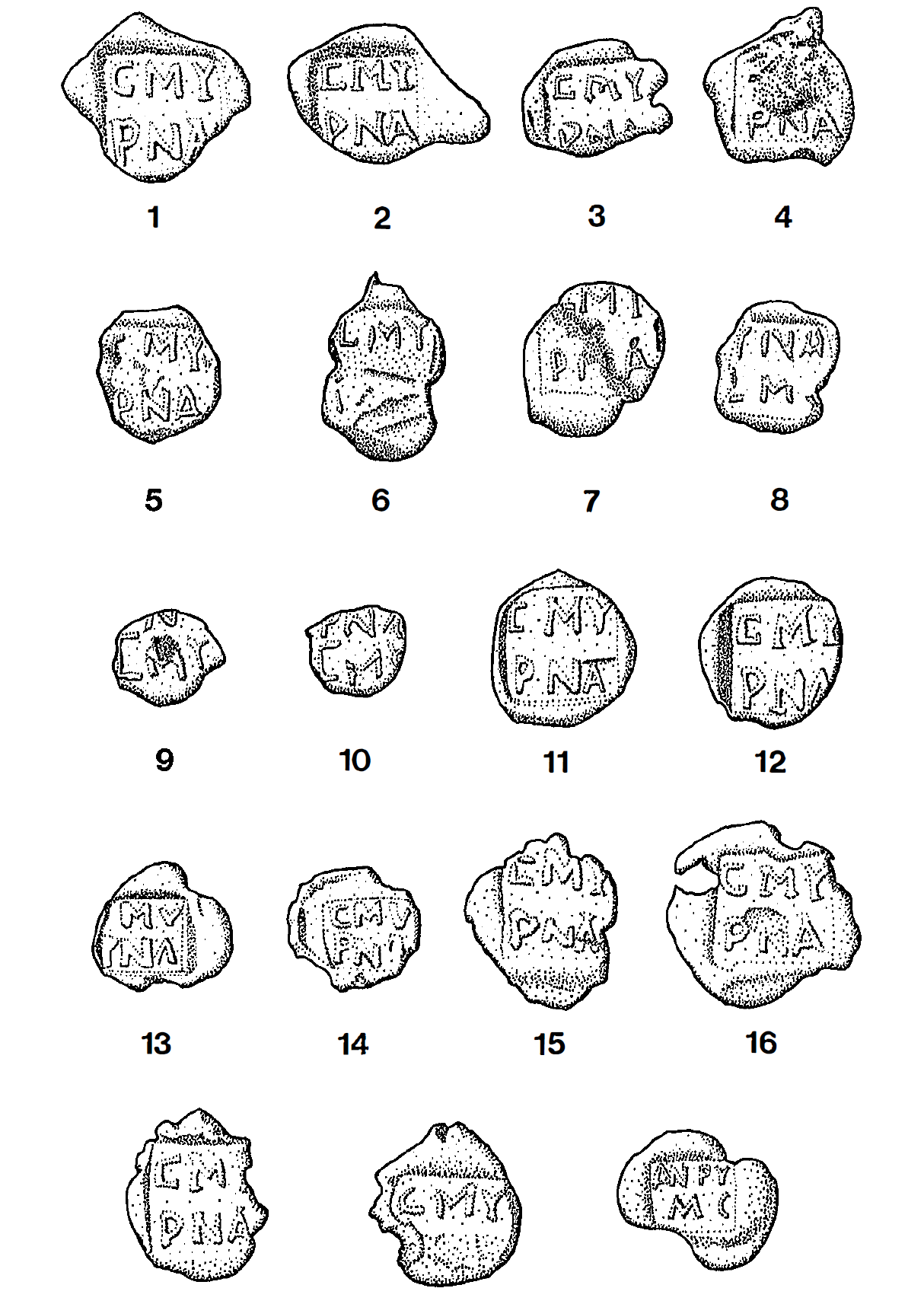

PARALLELS FOR THE ROMAN LEAD SEALING FROM SMYRNA FOUND AT !CK.HAM, KEN T. MICHAEL C.W. STILL, B.A. In 1977-79 seven Roman lead sealings were found during field-walking on the site of an unexcavated Roman masonry building c. 1100 m. to the south of the late Roman water-mill at Ickham 1 in the late Roman province of Maxima Caesariensis. Five of these examples were imperial, one depicting Constantine II as Caesar (A.D. 317-37) and the others bearing the titles and portrait of the emperor Julian (A.D. 360-363). All five of these are quite different in their method of manufacture from virtually any other known lead sealings. One of the remaining two was blank while the other bore the name of the city of Smyrna, modern Izmir in Turkey. It is this last sealing in which we are interested since there are close parallels from other parts of the empire (Fig. 1). Before looking at these other examples in detail it may be useful to give a brief description of what these sealings were actually used for, as far as is known. There are many different types of lead sealing, and almost as many uses,2 but it has been suggested that the Smyrna examples were a form of customs sealing, affixed either by the city or by the imperial customs office.3 They were not, therefore, necessarily attached to local produce but could have been used on goods passing through Smyrna from elsewhere, perhaps the interior of Asia Minor or even further afield. Presumably, they not only acted as a token to prove 1 For the sealings see M.W.C. Hassan and R.S.O. Tomlin, 'Roman Britain in 1978; II. Inscriptions', Britannia, x (1979), 350-3 and id., Britannia, xi (1980), 413 or RIB 2411.22, 25-28 and 41; for the water-mill site see C.J. Young, 'The Late Roman WaterMill at Ickham, Kent, and the Saxon Shore', in (Ed.) A. Detsicas, Collectanea Historica; Essays in Memory of Stuart Rigold, 1981, 32-40. The present location of the sealings is uncertain. 2 M.C.W. Still, 'Opening up imperial lead sealings', JRA, 6 (1993), 403-408. 3 G.C. Boon, 'Plumbum Britannicum and Other Remarks', Britannia, xxii (1991), 317-322. 347 l>J+>- 00 N t "' o 1. ICKHAM, MA'ilt1A CMSARIENS/S 2. S(ICIDAVA, SCY7//IA 3.ARZVS, THRACE 4-. LV6bUNUM, f.iALLIA L{lDVNENSIS PAIMA 5. SMYRNA, ASIA 0 IOOOK'!ll HCWS Fig. 1. Find-spots of sealings from Smyrna in relation to that city. 0 Cl) PARALLELS FOR THE ROMAN LEAD SEALING FROM SMYRNA payment of duty but would also have literally sealed the packages so that no smuggled goods could be added at a later date. They were attached using string which appears to have had molten lead poured on to it, just before the impression was stamped. The nine comparative examples (Fig. 3, nos. 2-10) cited for the lckham sealing when it was published in Britannia and RIB are from the site of Sucidava, in the province of Scythia within the diocese of Thrace, modern Izvoarele in Romania (Figs. 1 and 2).4 There are also three other examples (Fig. 3, nos. 11-13) from an unknown site (or sites) somewhere in the Romanian Dobrudzha, i.e. also in Scythia.5 Of Balkan provenance also are six examples of Smyrna sealings from the Roman province of Thrace, again within the diocese of Thrace. These are held in the collection of the Jambol History Museum, Bulgaria6 (Fig. 3, nos. 14-16 and 18-19), except for one which belongs to a private collector (Fig. 3, no. 17).7 These examples were all found on the site of Arzus near Kalugerovo, Haskovo Region (Figs. 1 and 2).8 There is one further example which I do not believe has previously been recognised.9 Dissard gives it as [.]NA/ LMY and suggests that it consists of a pair of abbreviated tria nomina: [.] N( ...) A( ...) (et) L(ucii) M(. ..) Y( ...). H e describes the inscription as being in two lines and the impression as rectangular.U nfortunately, no illustration of this sealing exists and its current location is unknown, but these details all suggest that it is similar to Culica's nos. 54-5610 (Fig. 3, nos. 8-10) 4 V. Culicll, 'Plumburi Comerciale din Cetatea Romano-Bizantinll de la Izvoarele (Dobrogea)', Pontica, viii (1975), 215-62, nos. 49-56 and 116 (although Frere repeats Hassall's error of omitting no. 56). There is some disagreement as to whether Sucidava lies within the province of Scythia or Moesia Secunda. 5 I. Barnea, 'Plombs byzantins de la Collection Michel C. Soutzo', RESEE, vii, 1, 1969,21-33,nos. 1-3. 6 For nos. 14-15 see M.C.W. Still, 'Some Roman Lead Sealings from Arzus', Poselishten Zhivot V Drevna Trakiya - III Mezhdunaroden symposium "Kabyle" (Settlement Life in Ancient Thrace - Proceedings of the Illrd International Symposium "Cabyle"), (Ed.) D. Draganov, 1994, 389-395, nos. 6-7. For nos. 16 and 19 see V. Gerasimova-Tomova, 'Tergovskite Vrezki na Arzos (I-III V. ot N.E)' ('Trade Connections of Arzus; 1st - 3rd C. AD)' in D. Draganov, op. cit., 371-88, nos. 19-20. Nos. 17-18 are previously unpublished. 7 My thanks to Dr Dimitar Draganov for allowing me to study his museum's large collection of lead sealings and for enabling me to examine an important private collection. 8 Opinions differ as to whether the site of Arzus lies within the province of Thrace or Haemimontus. I have adopted the former. 9 GIL XIII pars 3, fasc.2, 10029.144, originally published as P. Dissard, La Collection Recamier. Catalogue des Plombs antiques (sceaux, tesseres, monnaies et objets divers), 1905, Paris-London, no. 172. 10 Culica, op. cit., 244-5. 349 MICHAEL C.W. STILL which were impressed using a matrix with the two lines of the inscription in the wrong order: PNA / CMY. The 'L' is easily explained as a damaged 'C' since Culica's examples have an angular 'C' which resembles three sides of a square. It would appear that the majority of the sealings in the Recamier Collection are from the Roman waterfront at Lyons. This may well hold true for this example (Fig. 1). It may be helpful to suggest some possible routes that these sealings may have taken to reach their final destinations, although it is important to remember that this can only ever be speculative. It is known, however, that sea and river transport was preferred to land transport since it was much cheaper. 11 The sealing found in Ickham and that found in Lyons may well have taken the same route through the Mediterranean and along the west coast of Italy and the south coast of France. They would then have been transferred from a sea-going ship to a river craft at Arles and taken up the Rhone to Lyons. At this point, the Ickham sealing would have continued up the Saone and been unloaded for the overland journey to the Moselle, whence it could have reached Britain via the Rhine (Fig. 1).12 Another possible route for this sealing would have been up the Saone and then down the Seine, but the find-spot in Kent favours the more easterly route via the Moselle. Those found in the Balkans are only a relatively short journey by ship from Smyrna. The examples found in Scythia would presumably have entered the Black Sea and then travelled up the Danube or been unloaded at coastal ports to reach their sites, but those found in the province of Thrace would probably have been taken up the River Hebrus (modern Maritsa) from its mouth in the Aegean (Fig. 2). There is little profit in guessing at what goods may have been secured by these sealings. Various centres in the interior of Asia Minor were known for their textile production but there were also overland trade routes bringing silk from China, spices from India and incense from Arabia. One famous epigraphist originally believed that the inscription on the sealing from Ickham referred to the contents of its package, since aμupva is also the Greek word for myrrh. Although this is not the real meaning of the inscription, there is always the chance that myrrh could possibly have been one of the many products thus sealed. A comparison of the drawings of the actual sealings (Fig. 3) suggests that, excluding the obviously different examples of nos. 8, 9, 10 and 19, several matrices were used. However, the apparent difference in letter forms and size of impression seems to be due to the vagaries of both 11 K. Greene, The Archaeology of the Roman Economy, 1986, 39-40. 12 Cf. H. Clippers, 'Ausgewiihlte romische Moselfunde', Trierer Zeitschrift, 37 (1974), 170, no. 39 for a sealing from Trier which names Ephesus. 350 c..,J VI ...... -- - DIOCESAN BOVllbAR.Y -------PROVINCIAL BOUNPARY -RIVER RONTIER --RIVER. --COASTLIN£ 0 100 200 300 400km --- N t MOES/A S£CVNDA .. _____ ,r--, ...... ________ --T-- --- - \ I I I I I THRACE I J-IA£MIMONTUS I I •.V,zus BLACK SEA MCW5 I Fig. 2. The diocese of Thrace showing find spots of Smyrna sealings in the provinces of Scythia and Thrace (detail of Fig. 1). u:, j u:, I u:, ><: MICHAEL C.W. STILL 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Fig. 3. Smyrna sealings from Ickham [1] (after Hassall); Sucidava [2-10) (after Culica); unknown site(s) in Scythia [11-13) (from Barnea's photographs) and Arzus [14-19] (no. 19 after Gerasimova-Tomova). Scale 1:1 except [2-10] which are 1:0.9. 352 PARALLELS FOR THE ROMAN LEAD SEALING FROM SMYRNA the molten lead and, in some cases, of previous illustrators whose drawings I have had to work from. In fact, when my own transparencies of some examples are superimposed on the others, it becomes clear that, in the cases of nos. 1-7 and 11-18, we are looking at the products of only two different matrices. Although we do not know the material from which the matrices were made and thus their durability, this suggests that the manufacture of these sealings may have lasted for a comparatively short time. Even if the use of a bronze matrix on molten lead could continue for dozens of years then we are still left with the fact that the small amount of proposed matrices in use indicates that, despite these being one of the most numerous types of lead sealing known, the practice was fairly limited. The use of more than one design of matrix may show replacement of worn matrices over a period of time or may just represent simultaneous use of different matrices by several workers. Nonetheless, a total of only four recognised matrices would appear to suggest that the use of our sealings was never a major factor in the economic life of Smyrna. It may be convenient to list the matrices and the sealings that they produced as follows: Matrix A - nos. 1 (Ickham), 2-7 (Sucidava), 11-12 (unknown site, Scythia), 15-18 (Arzus). Matrix B - nos. 13 (unknown site, Scythia), 14 (Arzus). Matrix C - nos. 8-10 (Sucidava). Matrix D - no. 19 (Arzus). The main point of this present work is to examine the nature of the individual sites on which these sealings were found in order to compare them with the site at Ickham in an attempt to categorise it. Unfortunately, three of our sealings are from an unknown site (or sites) and therefore cannot be included in the following survey. An even greater misfortune is the lack of proper archaeological excavation on any of the known sites. This means that the true nature of the two most productive sites, Sucidava and Arzus, can only be deduced from random finds and references, sometimes only inferred, in the literary sources. This is rather unsatisfactory since the stated purpose of a site (e.g. mansio) and its actual function in the local economy may not necessarily be the same thing. LUGDUNUM, GALLIA LUGDUNENSIS PRIMA (MODERN LYONS, FRANCE) (Fig. 1) This was the capital of Gallia Lugdunensis Prima, situated at the junction of the rivers Saone and Rhone. It had developed into a 353 MICHAEL C.W. STILL prosperous commercial centre and therefore the intended final destination of any goods bearing a Smyrna sealing is impossible to ascertain. The hundreds of assorted sealings from this site appear to have been removed from their goods at the quayside and thrown into the river as soon as they were unloaded from the ships. It is impossible to say whether these goods were destined for official use or whether they were to be sold, either wholesale or directly to the public, on the quayside. This uncertainty over the final use of the sealings renders the site virtually useless as a means of explaining the building at lckham. SUCIDAVA, SCYTHIA (MODERN IZVOARELE, ROMANIA) (Figs. 1 and 2) Sucidava was a city on the southern bank of the Danube. The exact nature of the site is uncertain due to lack of excavation, but it was occupied from the sixth century B.C. until the early seventh century A.D. It has been suggested13 that Sucidava was one of two unnamed frontier towns which were transformed into customs stations after Valens made peace with Athanaric in A.D. 369.14 This treaty forced the Visigoths to confine their commercial relations with the Romans to these two towns. This would not in itself explain the presence of the large number of assorted sealings, approximately 140, which have been found here. However, it has been suggested to me that the site may have acted as an emporium, 15 presumably supplying the Visigoths who were probably allowed to cross the Danube and enter the city at certain times. This could explain the large number of discarded sealings from goods arriving here. Unfortunately, this specialised function of trading with barbarians cannot provide any real clues to the use of the Ickham site, although the apparently official organisation is of some interest. Imperial sealings are also present here, as at Ickham, but these are of poorer quality and may only indicate the presence of produce from imperial estates. ARZUS, THRACE (MODERN KALUGEROVO, BULGARIA) (Figs. 1 and 2) The ancient site of Arzus was a road station on the important route from Central Europe to the Bosphorus and beyond.16 As a mansio it 13 Barnea, op. cit., 23-24 and his note 7. 14 Themistius, Orationes x, 135 bed., (Ed.) W. Dindorf, 1832. 15 Pers. comm. with Dr. Andrew Poulter, University of Nottingham. 16 The site ('Arzo') is named as a mansio in the Bordeaux Itinerary, published in O. Cuntz, Itineraria Romana I, 1929, 568,9. This Itinerary is dated to the consulship of Dalmatius and Zenophilus (A.D. 333). The Antonine Itinerary, id., does not describe the function of any of its places and uses the form 'Arso' for this site. 354 PARALLELS FOR THE ROMAN LEAD SEALING FROM SMYRNA would have provided board, lodging and a change of animals for travellers holding warrants for the cursus publicus. However, in the later empire mansiones were also used to collect the annona and, in the fourth century, some may have been issuing supplies to mobile army units.17 This particular site has produced approximately 80 lead sealings, some possibly pre-Roman. Dr Gerasimova-Tomova of Sofia has told me that she believes that the site was used as an emporium. This is an attractive idea although we need to explore further this site's relationship to the emporium at Pizus, only 18 km. (c. 12 Roman miles) west along the road, founded by Septimius Severus in A.D. 202.18 The evidence of the sealings from Arzus would appear to show that the site was active long before and long after this date. This site also produces an interesting comparison with Ickham, in that it was subject to a certain degree of official involvement. This could be even more important if the sealings arrived at the site on account of its role as a mansio rather than as an emporium. This site has also produced imperial sealings but, as at Izvoarele, they are generally not of the same quality as those from lckham. This might suggest that they were being used by imperial estates, rather than any more important government body. ICKHAM, MAXIMA CAESARIENSIS (Fig. 1) The site lies on the probable line of the main Roman road from Canterbury to the Saxon Shore fort at Richborough. Surface finds had already indicated a large Roman masonry building. The site is only 8 km. (c. 5.4 Roman miles) from the city of Canterbury and 10 km. (c. 6.8 Roman miles) from Richborough, one of the main entrance ports to the diocese of Britannia, and therefore seems to have been rather too close to both of these large centres to have acted as a mutatio for changing horses, let alone a fully fledged mansio, especially considering the short and easy journey resulting from the flat terrain. The building is situated at the point on the main road which is closest to an extensive Roman industrial area with facilities for both metal-working and corn-milling. This latter site, 1100 m. to the north of our masonry building, has been convincingly interpreted as an official centre, set up to supply the Saxon Shore forts of Richborough and Reculver.19 Our building, therefore, may 17 H.P.A. Chapman, The archaeological and other evidence for the organisation and operation of the Cursus Publicus, June 1978 (P h.D thesis, University of London), 133-34 and 179-180. 18 R.F. Hoddinott, Bulgaria in Antiquity, 1975, 206. 19 Young, loc. cit. 355 M ICHAEL C.W. STIL L have acted just as a store or perhaps even as a guard post, positioned at the point where a tentative side-road, leading to the industrial site, may have left the main road. This is, of course, hypothetical but an official connection for the masonry building, beyond the presence of the lead sealings, does seem likely. This is reinforced by the nature of the sites of Izvoarele and Kalugerovo. However, we should not forget that these two sites have produced totals of c. 140 and c. 80 lead sealings, respectively, and can in no way be compared directly with lckham and its seven sealings. In conclusion, disappointingly little can be gleaned from a comparison of these sites. At both Sucidava and Arzus there is a sense of underlying official involvement which fits in well with what has previously been suggested about the Ickham site. This probably has little to do with any similarity in function or even with the often cited similarities between the frontier provinces of Britain and those within the diocese of Thrace,20 but more to do with the empire-wide increase in bureaucracy of the later Roman period. A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Mark Hassan, M.A., F.S.A. and Gavin Kitchingham, B.A. for their comments on drafts of this paper, but the opinions expressed and any inaccuracies remaining are the responsibility of the author. ABBREVIATIONS CIL JRA RESEE RIB Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Journal of Roman Archaeology. Revue des Etudes Sud-Est Europeennes. The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. 20 Hoddinott, op. cit., 20. 356