Earthworks Survey, Romney Marsh

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

The Development of Roof-Tiling and Tile-Making on some mid-Kent Manors of Christ Church Priory in the thirteenth and fourteenth Centuries

The Custom of Romney Marsh and the Statute of Sewers of 1427

Earthworks Survey, Romney Marsh

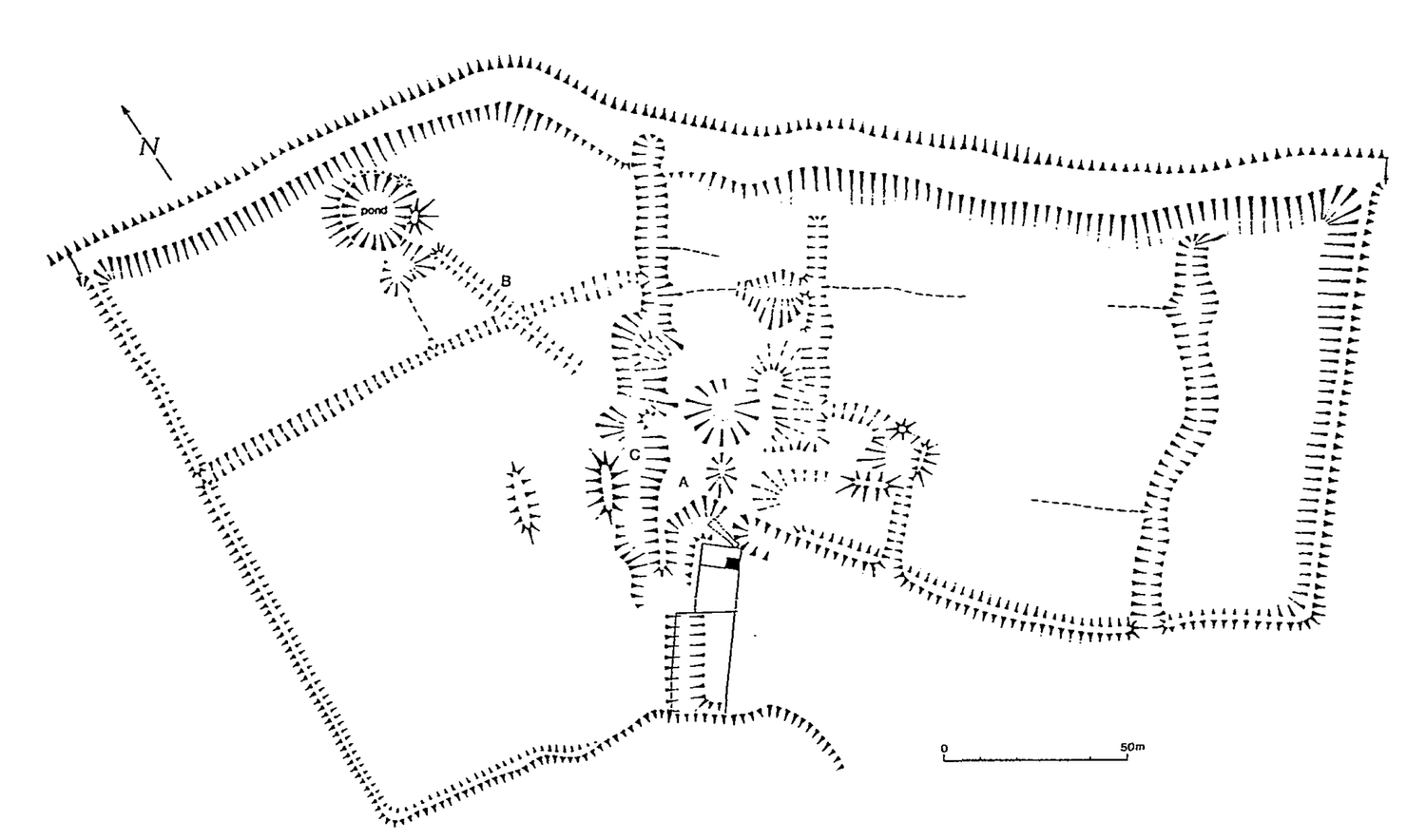

EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH ANNE REEVES INTRODUCTION Romney Marsh is a flat, fertile peninsula located between Rye in East Sussex and Hythe on the south Kent coast (Fig. 1). It forms a distinct region and is in fact a collective name for several marshes (or Levels). The Romney Marsh Level ( or Romney Marsh proper as it is known locally) comprises about 10,000 hectares and is located in the north-east of the region. This Level contains the most ancient land surfaces, and settlement was established here earlier than on other parts of the Marsh. Romney Marsh is not marsh in the usual sense of the word. Effective land drainage and defence against the sea have rendered it firm ground for centuries now, suitable for cultivation and habitation all year round. It has, however, always been a dynamic environment affected by changes in sea level, coastline and inundations over the ages. The Soil Survey (Green 1968) has mapped the complex depositional history of the area. In doing so it distinguished between 'older' decalcified and 'newer' calcareous soils, thereby revealing the courses of former rivers and tidal inlets. The earliest and most northerly of these, known originally as the river Limen, cut across the Romney Marsh Level from west to east during the Roman period. 1 Creek ridges similar to those found in Holland, and known as roddons in the Fens, are a feature of the Romney Marsh landscape. Former drainage channels that have become silted up eventually emerge as ridges as drainage causes differential shrinkage of the peat substratum - a process known as inversion. Green noticed a correlation between these creek ridges and early settlement. Wells and ponds supplying good quality water are also found on this land type. 1 The Limen was believed to be the original course of the Rother making its way across the Marsh from the Weald to the sea. However, recent research (Wass 1995) has shown that the Limen was not a river in the usual sense, but a truncated tidal inlet with marshland creeks and springs from the adjacent upland draining into it. 61 ANNE REEVES a 1km OoldSo11o □ -Sol•• F"-- Fig. 1. Location of surveys (Figure le based on Green 1968). These ancient watering holes have been known to graziers for centuries (Green 1968, 28, 110-11). A look at the Ordnance Survey map of the Romney Marsh Level today shows a maze of wandering dykes and small winding lanes. Parish boundaries follow the zigzag of irregular field boundaries. There is a distinct absence of straight lines in the landscape and the overwhelming impression is one of undeniable antiquity. Fields have been enlarged over the years, but the essential framework of the landscape has remained unchanged. Indeed, it is only by looking backwards that the extraordinary 62 EARTIIWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH shapes of some of today's fields and the frequent right-angle bends of the roads begin to make some sense. Amalgamations of the original smaller fields could not always proceed in a rational manner since established features had to be accommodated. Aerial photographs show hundreds of tiny fields, many as small as one or two acres, throughout the Romney Marsh Level (Fig. 2). These fields are basically rectangular and form a grid-like pattern, but there is no overall uniformity or cohesiveness. This distinct pattern holds 0 1km □ Old Soils 0 New Soils - Lower Wall Road !final course o/ the Umen) Direction ol Colonisation Progressive Innings Seawalls as plotted bi' Green (1968\ Fig. 2. Map of field boundaries on Romney Marsh Level taken from aerial photographs, showing direction of colonisation, progressive innings and pattern of field boundaries. (Based on Green 1968.) 63 ANNE REEVES clues to understanding the chronology of inning and the nature of early settlement. In the east the direction of inning and colonisation advanced north and west from the 'old' soil areas gradually moving towards the contracting flood-plain of the Limen. It is believed that this area was first settled between the ninth and eleventh centuries (Green 1968, 16, 36). Here a succession of wave-like frontiers can be seen; thus, although the field boundaries are frequently curving and irregular and seem to have proceeded in a piecemeal fashion, they also appear to have been simultaneously planned (in direction at least) to some extent. Similar, but less dramatic advances were made towards the Limen from the north. Roman finds confirm that land on the 'old' soil areas was settled much earlier. The existence of very small fields on Romney Marsh in the medieval period is verified by the fifteenth-century Terrier of Bilsington Priory (Neilson 1928, 62), but clearly a much earlier origin for the fields must be suspected. This system is entirely compatible with the most ancient features in the landscape, i.e. the hundredal and parish boundaries and the natural water-courses, and other archaeological features appear to post-date it. Furthermore, the pattern is distinctive and contrasts sharply with the regular planned thirteenth-century fields of near-by Walland Marsh and with other contemporary systems found in similar but more distant marshlands, e.g. the Lincolnshire Fens south of Holbeach, and near Godney in the Somerset Levels. The area flourished and was well settled and intensively farmed throughout the Middle Ages. But, by the sixteenth century, population had declined and much of Romney Marsh was laid down to grass. Land became concentrated in the hands of absentee landowners and sheep farming, originally pioneered by the monastic estates, predominated. Vital evidence about the past was sealed under a carpet of permanent pasture that lay undisturbed until ploughing in the twentieth century. In some places a complete medieval (or perhaps earlier) landscape has been preserved for hundreds of years in earthwork form. Ditches and banks mark out field systems and enclosures; and mounds locate the sites of former buildings. In 1991 and 1992, earthwork surveys were carried out over a sample area of 26 hectares (65 ac.) of Romney Marsh old pasture to assess the research potential and value for such recording. Work took place at seven locations, all on Romney Marsh Level and included land of both 'old' and 'new' soils as defined by the Soil Survey (Fig. 1). Simple ground plans were drawn at a scale of 1 : 500 and relief is indicated on the plans by hachuring. This paper consists of a descriptive account of these surveys with suggestions for their interpretation, followed by a brief discussion and some concluding remarks. 64 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH BELLFIELD, Bonnington (N.G.R. TR 067327) (Fig. 3) This field of 4.5 hectares (11 ac.) of old pasture lies to the south of the parish, 2 km. north-east of Newchurch. The land is 'new' calcareous soil and lies at 2 m. O.D. The western field boundary is the Eastbridge Sewer, a main water-course discharging into the sea at Dymchurch. Beyond the southern field boundary is the Newchurch road, a continuation of Lower Wall Road, which follows an ancient creek ridge associated with the former river Limen and marks the parish boundary between Bonnington, Newchurch and the former parish of Eastbridge. The field is transversed by a series of earthwork ditches which form an irregular grid-like pattern. These ditches are dry linear hollows which can be easily crossed by livestock and perform no function today. They vary in depth from 0.2 to 1.0 m. and the deepest fill temporarily with water in winter floods. Considering that these 'ditches' have received no maintenance in living memory, and perhaps for hundreds of years, they must have formed quite significant boundaries in the past.2 The earthwork ditches effectively divide the field into nine smaller plots which vary from 0.1 to 0.4 hectares (0.5-1.0 ac.) in size. There is a pond in the western half of the field which the ditches connect to. Two areas of very slightly higher ground were detected, but these are not thought to be of significance. The Tithe Survey of 1839 records this field as 11 ac. 3 r. 32 p. of pasture called Bell Field.3 The origin of the name Bellfield is not known but possibly it was once endowed land for the provision and maintenance of church bells and ropes, or for the payment of bellringers (Field 1972, 1989, 18). Alternatively, Bell might have been a personal name. Manuscript maps of the area show no former buildings at this location. Romney Marsh is fortunate in having a fine set of seventeenth- and eighteenth- century maps drawn for the purposes of evaluating land drainage rates. These provide exceptionally accurate surveys for the date. Bellfield is depicted with its present-day field boundaries in the mid-seventeenth century so the field system revealed by the earthwork ditches must predate this.4 No other documentary evidence relating to the field has been found. The ditches shown on the plan are all visible in aerial photo- 2 It has been estimated that, without maintenance, ditches would silt up quite rapidly on Romney Marsh, and cease to function effectively in ten to fifteen years. Without maintenance or grazing, small ditches could disappear altogether within 100 years. (Personal comment, G. Robinson.) 3 Centre for Kentish Studies: The Tithe Award for Bonnington (1840) U1772 07. 4 Centre for Kentish Studies: Map of Eastbridge Watering (1654) S/RM P2/3. 65 ANNE REEVES 66 . . .. .. . . . .. .. E lil 0 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH graphs.5 These earthwork ditches are remnants of a more extensive field system that once covered much of the Romney Marsh area. The small size of the plots suggests an early date. STONEBRIDGE FIELD, Lympne (N.G.R. TR 093337) (Fig. 4) This field lies between Newchurch and West Hythe on the north side of Lower Wall Road. The road follows an ancient creek ridge associated with the former river Limen and marks the parish boundary between Lympne, Burmarsh and the former parish of Eastbridge. The land is 'new' calcareous soil and lies at about 3 m. O.D. At one time the ditch along the southern field boundary formed part of the Hoomes Sewer, a main water-course that discharges into the sea at Dymchurch. This has now been diverted leaving only a small field boundary ditch. A mound and traces of earthwork ditches are visible in the south-eastern part of the field. Detailed survey was confined to this area. There is a sheep-fold in the south-west comer of the field. The earthwork ditches form a rectangular grid containing two small plots of land, one of which contains a sustantial mound about 2 m. high and 25 m. in diameter. The flat top measures approximately 10 x 12 m. and is horseshoe-shaped with two lower ridges extending out southwards but slightly offset from the alignment of the level top of the mound. The mound is imposed on the earthwork ditch system so it appears that the ditch system, which has no present-day function, is older than the mound. The existing roadside ditch (which was formerly part of Hoomes Sewer) curves around the mound site but also slightly cuts into the mound base. This cutting may have been caused by ditch maintenance. Local people claim that the mound has always been there. It was there in the present farmer's grandfather's lifetime. At the time of the Tithe Survey (1839) Stonebridge Field consisted of 16 ac. 2 r. 10 p. of pasture owned by Sir John Honywood and occupied by Stephen Southon.6 The field name derives from a near-by bridge. The mound is not shown on the Tithe Map.7 Although still pasture, most of the field has been ploughed and re-seeded except for this southern portion where the mound and remaining earthwork ditches are situated. The original eastern field boundary has been moved slightly westwards. Cultivation may account 5 British Geological Society: RAF 1946, 1:10,000, 4336. 6 Centre for Kentish Studies: The Tithe Award for Lympne (1839) U1772 050. 7 Centre for Kentish Studies: The Tithe Map of Lympne (1839) U1772 P38. 67 ANNE REEVES .- .... , , _ .. ,.. E fr1 l J - -- ---=- - ,..... ,..... -- --- ' ,..... ,... ...- - -- ...- ,..... ...- -- ...- - ...- --- ::: ...- ::.?0 \ \ \ \\\\\\\ \ \ \ \ \ 1 \ \L..-;. = -::111 \" \-;. - :- - .... - - -- - .. - ... ...- .. 68 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH for the slightly differing land levels observed within the field or this might be due to natural features associated with the near-by creek ridge. No evidence of the mound has been found on seventeenth- and eighteenth- century manuscript maps of the area, although this does not necessarily mean that it did not exist then. It is not shown on any Ordnance Survey maps either. No other documentary evidence relating to the site has been found. Aerial photographs taken in 1946 show that the earthwork ditch system originally extended over the whole field and beyond. The mound could not be clearly distinguished in the aerial photographs. 8 The Soil Survey mapped traces of an early sea-wall across the northern edge of the field (presumably dating from before the tenth century when the Limen was still in existence) and this can be picked out on the ground in the north-west comer of the adjacent field (formerly part of Stonebridge Field) as a slight bank about 0.5 m. high. The mound is higher, steeper-sided and overall more substantial than other former building platforms found in the area. It clearly post-dates the ditch system and may be a late medieval or sixteenth-century windmill mound possibly used in connection with pumping water along the Hoomes Sewer. The earthwork ditches in Stonebridge Field are similar to those found in Bellfield. They are remnants of an extensive field system that once covered much of Romney Marsh Level. These fields were probably medieval or perhaps earlier. EIGHT ACRES, Wey Street Fann, Ruckinge (N.G.R. TR 028316) (Fig. 5) This field of about 3 hectares (7 ac.) is on the south side of Wey Street 2 km. south from Ruckinge. The land is 'old' decalcified soil and lies at 2 m. O.D. The field is mostly old pasture but the western part has been ploughed and re-seeded. The field is divided into four smaller plots by earthwork ditches, up to 0.75 m. deep in places. These plots vary from 0.2 to 0.6 hectares (0.5-1.5 ac.) in size. The re-seeded area to the west (A) was originally subdivided and traces of a ditch remain visible (B). A small hollow with a diameter of 5 m. was noted in the re-seeded area. The small plots are rectangular in shape and form an irregular grid. Traces of ridge and furrow can be seen on two (as shown in the plan) and possibly three of the plots surveyed. This is extremely faint and only visible in very low light conditions. At the third plot (C) the ridge and furrow was too faint 8 British Geological Society. RAF 1946, 1:10,000, 4339, 4340. 69 ANNE REEVES ,,,, 50m I N I Fig. 5. Plan of Eight Acres, Wey Street Farm, Ruckinge. to record accurately. The most interesting feature is the different levels of the plots (Fig. 6). These levels are unlikely to be natural but their purpose, date and method of construction is unknown. The banks of the highest plot are about 0.5 m. high. Feint ridge and furrow was observed on both high and low level plots. The plot directly west from the highest area has extremely acid soil. There is no ridge and furrow here. The cause of this soil acidity is unknown, but it is not modern. The Tithe Survey records the field as Eight Acres owned by John Chennel and farmed by William Lord.9 Former farm buildings which are 9 Centre for Kentish Studies: The Tithe Award for Ruckinge (1838) U1772 064. 70 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH W EY STREET Low Medium High - - - 1------1 Medium Low Medium Low Low Fig. 6. Sketch map showing comparative land levels in and around Eight Acres, Wey Street Farm, Ruckinge. shown on the Tithe Map were situated in the west of the field close to the gateway to the road10 (D). The boundaries of this field have changed over the years. In the seventeenth century a map of the Brenzett Watering dated 1654 shows the north-south earthwork ditch (E) in the western half of the field as an existing field boundary .11 This ditch also marked the boundary between the Waterings12 of Sedbrook (to the west) and Brenzett. In the nineteenth century, the Tithe Map of 1838 shows this ditch still existing, but the north-south ditch by Wey Street Farm (F) is no longer maintained and the adjoining field to the east is included in the unit. By 1930 Ordnance Survey maps show this boundary reinstated and a strip of orchard planted beside it. At around this time ditch (E) ceased to function as an effective field boundary leaving the arrangement that exists today. No other documentary evidence relating to this site has been found. All the earthwork ditches shown in the plan can be seen in aerial photographs, but the ridge and furrow is not clear. 13 Maps show that this field system pre-dates the seventeenth century. The presence of feint ridge and furrow indicates that the field system 1° Centre for Kentish Studies: The Tithe Map of Ruckinge (1838) U1772 P44. 11 Centre for Kentish Studies: Map of Brenzett Watering (1654) S/RM P2/4. 12 Waterings were independently functioning units of land served by particular drainage channels or sewers which had to be regularly maintained. The system was overseen by the Romney Marsh Corporation, an elected body that evolved in the Middle Ages and operated successfully until the twentieth century. 13 British Geological Society. RAF 1946, 1:10,000, 4075, 4076. 71 t N I ANNE REEVES may be medieval, but the small size of the plots suggests an early date. The irregular grid-like pattern is consistent with that found over much of Romney Marsh Level. MARSHALLS BRIDGE, Dymchurch (N.G.R. TR 091299) (Fig. 7) This site is 1 km. west from Dymchurch village on the south side of Eastbridge road. It is set within a field of 4.5 hectares (11 ac.) of old pasture on 'old' decalcified soil and lies at 3 m. above O.D. The Soil Survey shows a minor creek ridge at this location. The site consists of a moat, now dry except in winter floods, which lies in the north-west comer of the present-day field, and a series of earthwork ditches that once divided the present field into smaller closes. The northern side of the moat is formed by the Marshland Course, a main sewer discharging into the sea at Dymchurch. Access from the road to the moated site and Fig. 7. Plan of Marshalls Bridge, Dymchurch. 72 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH the field beyond is across a bridge over the Marshland Course. Spoil from ditch maintenance now forms a bank all along the northern field edge obscuring any features that may have been there. Survey revealed a small but substantial moated site set within a ditched field system. The moat contains a roughly square island measuring 50 x 55 m. with a small depression on the west side. This was possibly a small pond on the island with a narrow outlet (former sluice?) into the moat. But the depression could have been formed later, if stone was robbed from the site, with the outlet dug subsequently to allow water collecting in the hollow to drain away. Evidence of former buildings was found on the island. The east side of the island is the highest part and rocks were discovered there where the surface of the turf had been disturbed. Broken tile and four sherds of pottery, including fourteenthcentury Pink East Wealden Ware, were found and rock was also observed on the south bank of the island. The south-west corner of the moat forms a spur and a feint trace of a former ditch (A) runs from the middle of the western side of the moat to the western field boundary ditch, which is the Jefferstone Sewer, a main water-course. The moat ditches are substantial measuring between 10 and 12 m. wide and more than 1 m. deep. Smaller earthwork ditches divide the rest of the field into a number of irregular-shaped plots. The Tithe Survey records this field as 10 ac. 3 r. 36 p. of pasture named Ten Acres.14 It was owned and farmed by Thomas Marshall at that date. Another Thomas Marshall owned land near by in the seventeenth century. No other documents relating specifically to this site or to the Marshall family and their possessions have been found. The name Marshalls Bridge probably derives from the nineteenth-century Marshall family, although Teichman-Derville has suggested a much earlier origin (Teichman-Derville 1936, 105).15 The moat itself is not shown on the Tithe Map nor on earlier manuscript maps. This is not unusual since these maps generally only depict features that affect land ownership. It is not indicated on modern Ordnance Survey maps either. However, careful study of early manuscript maps of the area reveals much indirect information about this site and its location, especially in relation to parish boundaries and water-courses. The western side of the moat formed part of the parish boundary 14 Canterbury Cathedral Archives: The Tithe Award for Dymchurch (1843) TO/D7A. 15 Teichman-Derville links the name with the twelfth-century holdings of Horton Priory which included Romney Marsh land tenanted by Erininilda, wife of Osbert the Mariscall or Marshall. Great Mascal Field lies just north of the moated site, but this connection remains tenuous. He goes on to link near-by Sutton Farm with the Domesday entry of Sturtune, but the location of this Marsh land remains a matter for speculation. 73 t N I t N I ANNE REEVES - ,.- DYMCHURCH HOORNES WATERING Main watercourses Watering boundaries Fig. 8. Sketch maps showing former parish and watering boundaries near Marshalls Bridge. between Dymchurch and the former parish of Orgarswick (Fig. 8). This parish boundary curves curiously, following the south-west comer of the moat before continuing south, then west across the field following one of the earthwork ditches (B). The western boundary of the existing field was the parish boundary of a former detached part of Sellindge. This Sellindge land was the subject of a late seventh-century charter and as 74 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH such is one of the earliest documented areas of settlement on Romney Marsh (CS 98; S 21, 697/700; Ward 1936, 11-28). Thus, the moated site was strategically placed and its location may have ancient tenurial implications. Early maps also reveal changes in the main water-courses over the ages. For land drainage purposes Romney Marsh Level was formerly divided into Waterings. Although known to exist in the sixteenth century, the Marshland Course is believed to be one of the later man-made drainage channels, in contrast to the Hoornes or Willop Sewers which were adapted from natural creeks originally draining into the Limen. 16 On the Poker Map of 161717 it can be seen that the Jefferstone Sewer flowed through the Sellindge land and divided at a point called Quytters. The eastern branch reached close to this moated site and may have connected to the moat through the earthwork ditch (A). This is curious and requires investigation. Why would the moat have been supplied with water from the Jefferstone Sewer when it was adjoining the Marshland Course? (Fig. 8) Possibly the moated site was strategically located to maintain a link between these two water-courses and the different Waterings in which they were situated; or, alternatively, to supervise the activities of the Waterings when conflicting interests were at stake. The Marshland Course may not have always formed the northern boundary of the moat. If the moated site was in existence before the construction of the Marshland Course, then it would have necessarily originally been supplied with water from the near-by Jefferstone Sewer in whose Watering the site was situated. This does seem the most likely explanation. Therefore, if the Marshland Course was not established until the thirteenth or fourteenth century as is suspected, an earlier date must be suggested for the construction of the moat. The Moated Sites Research Group have found that, although moats were built throughout the period from the twelfth to the sixteenth century, construction appears to have reached an apogee between 1200 and 1325 (Le Patourel and Roberts 1978, 51; Wilson 1985, 7). A moat of the type found at Marshalls Bridge would be consistent with a thirteenth-century date. The fourteenth-century pottery finds from the surface of the site suggest only that the site was occupied at that 16 This is evidenced by its relatively direct route to the coast achieved by a series of straight alignments closely following the road. This water-course may have been constructed as a result of monastic investment in a bid to improve land drainage at the Manor of Orgarswick whose land it passes through. Orgarswick Manor was held by Canterbury Cathedral Priory throughout the Middle Ages. (Personal comment, E. Vollans.) 17 Centre for Kentish Studies: Map of Romney and Walland Marshes by Matthew Poker (1617) U l823 P2. 75 ANNE REEVES date, but have no bearing on dating its construction. Only excavation can solve the problem conclusively. It was noted earlier that the moated site was set within a field system marked out by earthwork ditches. The ditches shown on the plan are all visible from aerial photographs (except for the feint westerly one) and some can be seen to have continuous alignments across adjoining fields. 18 The moat and the depression on the island can also be clearly seen in aerial photographs. Survey has revealed that some of these earthwork ditches may have pre-dated the construction of the moated site. The east side of the moat cuts off an earthwork ditch (C) running from north to south across the present-day field which suggests that this ditch was already in existence when the moat was constructed. This earthwork ditch is now comparatively shallow. It may have ceased to function as a field boundary after the construction of the moat or perhaps just received less maintenance over the centuries than other ditches which performed additional functions serving as parish boundaries. It is interesting that the moat utilises ancient ditches, such as the former Orgarswick parish boundary ditch (B), which originate from former natural creek relics. This ditch was probably realigned to incorporate the moat and avoid crossing the land contained by it.19 Although placed at a significant location the moated site at Marshalls Bridge was not a Manorial centre (Teichman-Derville 1936, 96-112).20 In form it is a simple, square moated site probably of thirteenth-century date. It is set within and appears to post-date the surroundings field system, which is consistent with that found over much of Romney Marsh. The complex pattern of boundaries make this location a peculiarly strategic site worthy of further investigation. SHEEPHOUSE FIELD, Dymchurch (N.G.R. TR 093298) (Fig. 9) This field of nearly 5 hectares (12 ac.) of old pasture is on the south side of Eastbridge road, less than 1 km. from Dymchurch village centre and the sea. The land is 'old' decalcified soil and lies at 3 m. O.D. The Marshland Course main sewer forms the northern field boundary. A sheep pound, brick-built sheep-house (shepherd's or 'Looker's' hut) and 18 British Geological Society. RAF 1946, 1:10,0900. 3062, 3063. Potato Marketing Board, 1979, 1:7,500, 6087, 6088, 6089. 19 Personal comment, E. Vollans. 20 Teichman-Derville listed and located twenty-three Manors in the Romney Marsh area. 76 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH 77 ANNE REEVES a brick sheep-wash are found in the south of the field. These are believed to date from the nineteenth century. Earthwork ditches preserved in the pasture divide the present field into a number of smaller closes. These are basically rectangular but vary in size and shape, the smallest being closest to the sheep-house. These earthwork ditches are dry today but some carry water temporarily in wet winters. There is a deep pond in the north-west quarter which is an ancient watering-hole. Survey produced a complex plan showing a number of earthwork ditches, hollows and mounds. The whole area has a very disturbed appearance and clearly contains features from different periods. The field is divided into smaller closes by a complex pattern of earthwork ditches. Two of the ditches, those running from north to south, divide the land into approximately equal-sized rectangular plots. Others connecting to them and to the pond are shallower and appear less significant. Directly north of and adjoining the sheep-house is an area of slightly elevated ground (A). Here quantities of tile and rocks, presumably the remains of former buildings, can be seen where the turf has been disturbed. (Other tiles found closer to the sheep-house probably came from it.) There are a number of small depressions within this high area which may have been caused by subsequent robbing of building materials from this site. There are two significant small mounds. One, almost 1 m. high and about 12 m. long, is probably the result of widening and deepening the main ditch crossing from north to south. The other, further west, is isolated from the other feature. It is less than 0.5 m. high and about 15 m. long. Other features include a shallow depression just east of the area of high ground, which could have been a small shallow pond at one time. It is connected to an existing ditch by earthwork ditches. More interesting is a feint, slightly raised causeway (B) about 100 m. long which links the area of high ground to the present-day pond in the north-west part of the field. The causeway cuts across one of the east-west earthwork ditches and appears to overlay it. Two isolated sherds of pottery were found in the field, both pink sandy wares of fourteenth-century date. The Tithe Award records this field and as 12 ac. 0 r. 23 p. of pasture named Eleven Acres.21 The sheep pound is marked on the Tithe Map but the sheep-house is not indicated so must have been built after 1842.22 Most surviving shepherds' huts on Romney Marsh date from the eighteenth or early nineteenth century. Interestingly, sheep-folds and huts were often constructed on the sites of former medieval farmsteads, perhaps because the ground was already somwhat elevated and compacted 21 Canterbury Cathedral Archives: The Tithe Award for Dymchurch (1843) TO/D7A. 22 Canterbury Cathedral Archives: The Tithe Map for Dymchurch (1842) T0/07. 78 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH at such spots making ideal foundations for further building. Alternatively, the connection may derive simply from the location of earlier smaller farming units that became amalgamated over time and eventually lost altogether. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century manuscript maps show the field boundaries in their present-day form but some buildings can be seen from a map of 165223 on the area of high ground just north from the sheep-house and pound at (A). Most of the earthwork ditches can be clearly seen in aerial photographs.24 The Soil Survey shows that the sheep-house and the site of former buildings are situated on an ancient creek ridge. No other documentary evidence relating to the site has been found. The earthwork ditches recorded in this field are similar to those found elsewhere in the area and some have alignments which continue into adjoining fields. It is not possible to ascertain by ground survey alone whether all the ditches were contemporary. Some may have been added at a later date. Alternatively, priorities may have been decided regarding the maintenance of the ditches within the system over time, which resulted in some ditches surviving in a more substantial form while others were neglected. Logic suggests that the smallest closes must be the oldest features, with the deepest north-south earthwork ditch (C) probably maintained longer than the rest but eventually being disregarded when a larger land unit using the present-day field boundaries was favoured (by 1650). Buildings on the elevated ground on the north side of the sheep-house (A) were still in existence in 1652, but they appear to have been lost by 1759.25 Pottery found within the field is evidence of activity there in the fourteenth century. The causeway linking the site of the former buildings to the pond was constructed after the establishment of the field system, but its function remains a mystery. The most likely explanation for this site is a medieval farmstead (abandoned in the seventeenth or early eighteenth century), which was originally set within and post-dated a field system consistent with that found over much of Romney Marsh. The field system was adapted over time for sheep farming by enlarging the fields, establishing sheep pens and eventually building a shepherd's hut in the nineteenth century. 23 Centre for Kentish Studies: Map of Jefferstone Watering by Thos. Boycote (1652) S/RM Pl/2. 24 British Geological Society. RAF 1946, 1:10,000, 3062, 3063. Potato Marketing Board, 1979, 1:7,500, 6087, 6088. 25 Centre for Kentish Studies: Map of Jefferstone Watering by Thomas Hogben (1759) S/RM P4/2. 79 ANNE REEVES TWELVE ACRES, Burmarsh (formerly Eastbridge) (N.G.R. TR 090336) (Fig. 10) This field of old pasture is situated in the north of the former parish of Eastbridge (now Burmarsh), about 3 km. north-east of Newchurch. The northern field boundary follows the Lower Wall Road which marks the parish boundary between Lympne and Burmarsh (or the former parish of Eastbridge). The land is 'new' calcareous soil and lies at 3 m. O.D. This wedge-shaped field is divided into a number of smaller closes by earthwork ditches and there is a mound close to the northern field boundary. There is a barn and fenced sheep pen in the south-east field comer, but this is not old. There was formerly an old sheep-fold where the barn is now sited. Survey revealed that the present field is divided by earthwork ditches (now dry except in winter floods) into ten small enclosures varying in size and shape. Sizes of the plots range from 0.2 to 0.6 hectares (0.5- 1.5 ac.) the smallest being closest to the mound except for one small strip adjoining the southern field boundary where the land level rises slightly. The mound is about 1.5 m. high and is situated within a small ditched enclosure of about 30 x 60 m. The level top of the mound is approximately 11 x 9 m. There is a small curving linear depression from the top of the mound to the ditch on the west side. Other features include two isolated and very slight mounds in the western half of the field which are not believed to be old.26 There are also considerable embankments (up to 1 m. high) around a pond formed where the western field boundary has been widened. There is a curious arrangement of ditches at the point where the embankment is highest whereby a small 'island' is formed. This is in alignment with a series of features in the next field to the east. In the Tithe Survey of 1840 this field was recorded as 12 ac. 3 r. 2 p. of pasture, owned by Harry Carter and farmed by Henry Cook.27 The field name was Twelve Acres and a pound (sheep-fold) is noted. No buildings are shown here on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century manuscript maps and the existing field boundaries appear unchanged since 1654.28 Aerial photographs clearly show the pattern of earthwork ditches. 29 No other documentary evidence relating to the site has been found. 26 This is probably spoil from clearing ant-hills. Slight mounds like these are often found in old pasture and are known locally as emmett heaps. 27 Centre for Kentish Studies: The Tithe Award for Eastbridge (1840) U1772 063. 28 Centre for Kentish Studies: Maps of Hoornes Watering (1654) S/RM P2/5, (1762) S/RM P3/5. 29 British Geographical Society. RAF, 1:10,000, 4339, 4340. 80 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH ,11111111111,,,,, ,,,,,,,, 111n1 ' \Z ll q..11 I I .... ,,/,,,, ,, ,,,,,.,,\1\L11ll • 1 l}t ::: ',,, ,''r, , ,,,,\,,•1•1 :: 0-= ,,, ,,, .,,.,, 1111 -- == ,,, ,, 11\II, ,\I -- -- 1, ff •• 11•11\ \ -- ,,,... -- ,, ,, i \\· =»<.:' ,./;:: '•/.( .... ......... ff"" --- .,,., \ Pi11l ,. \ . ,, r I 11111 I r r I I 11 I 1 I I I I 1 I , , I I I ,, ,,, , , , , , I I I , ,, /I I I I I f f I ....L,t l I i I ., .... 1 1 1 I 1 1 1 1 1 I I I J I i l.,,.. \. I I I I 1 1 I I I I I I I i I i J l , I l I JI 1' I .J>--" ... .... - - " .. ,. ' - . - = : : : = : - ... ► .. - ·. - - . - - : , . - -i: :: . .. .. .. . -. ..... ... .. ◄... • ... - - - . ... ·'' :t --:. .. ◄► .... ◄► ... .. - .. .. .. .. ◄► ... .. - ... .. ◄► ...... : == ◄... ' ... , --- - - : : .. ,.., ,11'\ • '\ l! p' f I I' - - .,. "' -j \I 1 ·, : ', 1 l I J/ \ ,--J J j J l J ; 1 J ;,•:::III I l I II,, ,, I II I I r I r If ff,: ... \i\l ..- ... IAJ.1.1,11111,,1,i,,,11 ❖l -;.:: ''': -- -- 0 Fig. 10. Plan of Twelve Acres, Burmarsh. . . I N I 60m ANNE REEVES This field system is remarkable for its arrangement within the framework of the existing field boundaries. It appears to be a complete selfcontained unit. The curious arrangement of ditches on the west boundary aligned with similar features in the adjoining field to the east may relate to the existence of the former river Limen. The small size of the closes and unity of the system suggest an early date. The mound is probably a raised building platform. Similar platforms have revealed concentrations of shingle, pottery sherds and other building materials on ploughing. Only excavation can determine a reliable date for this site, but the mound appears to be contemporary with the field system, so a farmstead of early medieval date is suspected. NINE ACRES, Burmarsh (formerly Eastbridge and Burmarsh) (N.G.R. TR 091337) (Fig. 11) This unusually shaped field of old pasture is situated south of the Lower Wall Road about 3 km. north-east of Newchurch. A ditch running from north to south across the middle of the field marks the boundary between the former parish of Eastbridge and Burmarsh, and the road to the north forms the boundary with Lympne parish. The land is 'new' calcareous soil and lies at 3 m. O.D. The eastern field boundary is formed by the Hoornes Sewer, a main water-course that discharges into the sea at Dymchurch. This sewer was originally a natural creek that flowed into the Limen centuries ago. There is a modem bungalow in the north-west field comer that was constructed on the site of an earlier cottage. An old well is located in the field just south from the bungalow. The field contains a complex pattern of earthwork ditches and hollows. This field is unusually long, measuring 350 m. from east to west and only 80 m. from north to south. Survey revealed that it is divided into nine smaller plots by a series of earthwork ditches, some of which carry water in wet winters. These form an irregular grid but the pattern is complicated by a series of shallow hollows, 0.25-0.5 m. deep, particularly in the western part of the field. There are subtle changes in level across the field and one small area of ground situated close to the central parish boundary on the northern field edge is slightly higher than any other part of the surrounding field. The Tithe Survey (Burmarsh 1843, Eastbridge 1843) records the field as 9 ac. 1 r. 27 p. of pasture named Nine Acres, owned by Montague (late Lord Rokeby) and farmed by John Prebble.30 Other manuscript 3° Centre for Kentish Studies: The Tithe Award for Burmarsh (1843) U1772 017. The Tithe Award for Eastbridge (1843) U1772 063. 82 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH 83 ANNE REEVES t Sluices ]\1 Approximate position of seawall I as mapped by Green (1968) Fig. 12. Sketch map of Nine Acres and Twelve Acres showing position of proposed sluices and sea-wall. maps show that apart from the loss of the central north-south ditch marking the parish boundary, the existing field boundaries have remained unchanged since the mid-seventeenth century.31 No other documentary evidence relating to the field has been found. All the earthwork ditches shown on the plan are visible on aerial photographs.32 Although the earthwork ditches in this field are similar to those found over much of the area, the complex pattern of ditches and hollows requires further explanation. The proximity of this site to Hoornes Sewer, an ancient water-course, and the channel of the former river Limen are crucial; and a possible link between the features of this field and local riparian devolution cannot be ignored. The Soil Survey discovered a possible sea-wall running from west to east through the southern part of this field (Fig. 12). Although not as distinct as that found in Stonebridge Field near by, subtle changes in land levels are discernible which relate to this feature. The shallow hollows, regularly spaced along this alignment, may mark the positions of sluices discharging into the former river as inning progressed and the river contracted during the Saxon period. 31 Centre for Kentish Studies: Maps of Hoomes Watering (1654) S/RM P2/5, (1762) S/RM P3/5. 32 British Geological Society. RAF 1946, 1:10,000, 4339, 4340. 84 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH If this hypothesis is correct, then this land must have always been pasture. The features would have originally been quite substantial but, unlike the adjoining field (Twelve Acres), there was obviously never sufficient incentive to level them and re-allot the land. This would also account for the unusual shape of the present-day field. As surrounding land was utilised for arable production in the early medieval period, long after the loss of the Limen and the colonisation of land where the former channel flowed, this long narrow strip of bumpy ground remained. Alongside the Hoomes Sewer, it must always have been wet and perhaps liable to winter flooding. Fortunately, so far, it has also survived the arable revolution of the twentieth century. Much further work needs to be done to verify this hypothesis, but it is a potentially very exciting discovery and one that could throw much light on the chronology of landscape evolution on Romney Marsh Level. The small area of slightly higher ground close to the road may mark the site of former building. DISCUSSION Of the 26 hectares (65 ac.) of old pasture surveyed on the Romney Marsh Level, all seven locations produced evidence of former field systems in earthwork form. Other sites discovered by the survey and described here include a medieval moated site, sites of medieval buildings and other significant landscape features. Much of this can be seen in aerial photographs of the region, but only field survey reveals the full complexity of the features. Dating remains problematical without documentary support, but detailed survey enables the relationship between features to be carefully studied. Where one feature is imposed on another the succession of events becomes apparent. Thus, it is possible to suggest a chronology \ for the evolution of this landscape and the activities of those who lived within it. Field Systems Scattered settlement and irregular field boundaries are, on the whole, typical of Kent, but the very small size of fields found on Romney Marsh Level does require some explanation. Data from field survey and the Bilsington Priory documents show an average field size of less than 0.8 hectares (2 ac.), a figure comparable with the prehistoric fields found on the chalk downs and in the west country. Roman settlement along the coastal siltlands of the Wash produced similar small fields. These were square or roughly rectangular fields, often as small as 0.25 hectare, bounded by drainage ditches. They were arranged in a haphazard manner 85 ANNE REEVES and appear to be the result of piecemeal or unplanned expansion (Taylor 1975, 54-6). The area has much in common with Romney Marsh, but the field pattern is quite unlike the regular grid-like Roman fields found on the north Kent marshes and along the Severn estuary. Any attempt to understand the evolution of field systems must necessarily take into account a variety of local factors, including soils, climate, land use, land ownership and tenurial arrangements. It is well known that the Kentish peasantry enjoyed an exceptional measure of personal freedom in the Middle Ages. Much of Romney Marsh was held in ecclesiatical hands. Canterbury Cathedral Priory pioneered in adapting customary tenure to new leasehold arrangements on their Marsh lands. Labour services were commuted at an early date. By the end of the twelfth century, records show that desmesne lands of monastic manors on the Marsh were let out on liberal terms to large numbers of small tenants (Smith 1943, 113-14). Small-scale freeholders also maintained a presence. Clearly, seignorial control was weak. The independence and strength of the Romney Marsh Level peasants is evidenced by their petitions to the courts and the king forcing powerful institutional landowners to contribute towards the upkeep of sea defences. Local laws governing the maintenance of sea-walls and watercourses for common benefit and safety were administered by officials elected by the Commonalty, i.e. all local inhabitants, not imposed by Lords. This system was already old by the thirteenth century (Teichman-Derville 1936, 73-4). The Marsh, it seems, had long been populated by large numbers of unusually independent small farmers. It is not surprising, therefore, that as new land was colonised, settlement was characterised by the highly individual piecemeal inning already described. But does this alone explain the small size of the enclosures? Assuming that the Romney Marsh fields are not prehistoric33 or Roman, it must be considered whether they were simply the result of particular methods of inning or whether there is any evidence to suggest that the original innings were subsequently divided. The practice of Gavelkind (partible inheritance) must have affected field size and morphology; and the fluctuating relationship between population and land availability would have been critical, but land use and soil limitations must have been equally important. Although ditches serve as barriers their primary function is to facilitate drainage. Drainage was vital to the population of the Marsh, without it they could not survive. However, the extensive network of 33 So far the only evidence for prehistoric occupation on Romney Marsh Level derives from two late Iron Age pottery sherds found on 'old' soil near Burmarsh. 86 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH ditches found would have been unnecessary for the effective drainage of grassland alone. Thus, these small fields most likely date from a period of extensive arable cultivation. Anglo-Saxon charters enumerate ploughlands on Romney Marsh and considerable settlement is recorded by the time of Domesday but detailed documentary evidence of cultivation does not occur until the thirteenth century (Smith 1943, 130, 140). Fieldwalking evidence is more instructive about the Marsh in the Middle Ages. The picture revealed is one of an area of scattered or dispersed settlement with a population far higher than that of today. Field-walking evidence suggests that the Romney Marsh population was highest before 1250, declining gradually thereafter to 1450 when a sharp decline set in. Calculations based on a sample area show an average of one site for every 6 hectares (15 ac.) of land in the medieval period. Not surprisingly, this level of population required a great deal of arable land. Fieldwalking was also able to gather data concerning the extent of medieval arable cultivation by plotting background pottery scatters that were deposited when the land was worked and manured. This showed that more than 70 per cent of the sample area was cultivated and included pottery sherds dating from the twelfth century (Reeves 1995).34 Some of this arable land could represent short-term, temporary or experimental arrangements. The feint ridge and furrow at Weystreet may be such an example. The antiquity and small-scale, independent nature of the original innings goes some way towards explaining the unusual field pattern found on the Romney Marsh Level, but the small size of individual fields must have also been linked to land use and the requirements of cultivation. It is possible that some small fields were established on 'old' soil areas in the Roman period. Progressive innings show no abrupt dislocations at the interface between 'old' and 'new' soils. However, an overview of all the available evidence suggests taht the main focus of activity must have occurred in the late Saxon period when favourable climatic and environmental conditions would have assisted the inning process. By Domesday, the framework of the Romney Marsh landscape was laid out and becoming intensively settled. It cannot be ruled out that some small enclosures were created later, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, by dividing and draining grazing land as population pressure increased and more arable land was needed. Possibly the field system in Twelve Acres, Burmarsh, is an example of this. It is also important to remember that in places subsequent development overlays and therefore 34 The field-walking in this study was confined to Romney Marsh Level. 87 ANNE REEVES post-dates the early fields, e.g. the medieval moated site at Marshalls Bridge, Dymchurch. There is no evidence to suggest any large-scale planned reorganisation of the landscape at any time. The earthwork ditches that remain represent an ancient farming system and are a testimony to the ingenuity and adaptability of the Marsh inhabitants in those early years. Other Features Other features discovered by this survey include the moated site at Marshalls Bridge, Dymchurch, and the possible mill mound in Stonebridge Field, near Lympne. Few documentary records of medieval mills on Romney Marsh have been found. Mills can be seen on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century maps of the area35 and mill field names dating from the thirteenth century have been found. The function of these mills remains unclear. Cereal crops such as wheat, barley and oats were grown on the Marsh throughout the medieval period, so presumably some mills were employed grinding corn. However, it would not be unusual to find also water-pumping mills in such an environment. Sixteenth-century documents describe the construction of an 'engine' to pump water on Walland Marsh, near Woodruffs, but it is not clear whether this was wind-driven.36 No archaeological evidence of this or any of the other mills shown on maps has been found. There is, therefore, no comparative evidence with which to consider the possible mill mound in Stonebridge Field. It appears to be an isolated example and parallels must be looked for further afield, e.g. in East Anglia, the Somerset Levels and in the Low Countries. Moated sites are far more common. They have been found in every county of England and seem to be especially concentrated on damp clay soils in lowland areas characterised by dispersed settlement. The Sites and Monuments Record for Kent lists 128 moated sites within the county. About 70 per cent of all known moated sites came into being in the period 1200-1325 and most were occupied by aspiring freeholders. Research has shown that moats were constructed in many shapes and sizes and often performed a variety of functions (Wilson 1985, 15). In a location such as Romney Marsh, close to the sea and where watercourses and water-borne transport were of great importance, access to 35 Centre for Kentish Studies: Map of Romney Marsh (MS copy of Cotton Augustus 1 no. 24, c. 1590), S/RM PS. Map of Romney and Walland Marshes by Matthew Poker (1617), U1823 P2. See also: Tatton-Brown 1988, 106, 109. 36 Centre for Kentish Studies, S/RM/Z9 and ZlO. 88 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH the sea at Dymchurch via the Marshland Course may have been a significant factor for occupants of the Marshalls Bridge site and others near by. Evidence from west Kent suggests an evolution of moat form from round (earliest) to square to rectangular (latest).37 Moated sites of comparable dates are found over much of north-west Europe. In Flanders, where they are very common, it is believed that their distribution was linked to the ancient system of land-holdings rather than originating from environmental factors (Verhaeghe 1981, 149). Research in Bedfordshire found a similar correlation (Brown and Taylor 1991, 38). The important strategic location of Marshalls Bridge suggests similar factors may be at work in Kent. Altogether the Romney Marsh area has fourteen known moats38 (including Marshalls Bridge), but only one is confirmed as the site of a Manor. Nine of the sites are located in Romney Marsh Level. Another three moats are suspected from aerial photographic evidence. Of the fourteen positively identified, one is circular, four are square and nine are rectangular. Marshalls Bridge is the only suriviving square moat. The others have all been destroyed or damaged by ploughing and no detailed survey or excavations have been carried out on any Romney Marsh moats. Further comparisons are therefore impossible. Perhaps the most exciting discovery made by this survey are the features in Nine Acres and Twelve Acres associated with the former Limen water-course. For centuries the security of Romney Marsh has depended on walls to protect the land from inundation by sea and rivers. Many walls have been lost, and it is not known which of those upstanding walls that survive inland today are oldest, although a chronology for the innings of Walland Marsh in the Brookland area has been put forward (Tatton-Brown 1988, 105-11). Walls identified with some certainty were mapped by Green at the time of the Soil Survey. The first documentary evidence of walls on Romney Marsh appears in the twelfth century when grants of land near Appledore in the west contained covenants concerning maintenance obligations. Green believes that 'a large number of walls must have existed by this time, although many were probably to protect land long settled and farmed, or to reclaim it following flooding, rather than to enclose primary saltings' (Green 1968, 18). By the thirteenth century the main line of defence against the sea for Romney Marsh Level had shifted to the Dymchurch Wall in the east. The Soil Survey also picked up some older and very slight embankments marking the channel of the former river Limen across the north 37 Personal comment, T. Hollobone. 38 Only five of these are recorded in the county Sites and Monuments Record at present. 89 ANNE REEVES of Romney Marsh Level. The original land drainage' of the land type found here is difficult to chart as many relic creeks wer filled in during field reorganisation. They can be seen as narrow sinuous depressions on aerial photographs. Others are preserved as sewers, or their banks used as tracks and roads. Green discovered clear links between existing landscape features and the former course of the Limen: 'From the name of the associated road, Lower Wall, and the fact that at one time it coincided with parts of the boundaries of seven parishes, it is likely that this was an important feature in the landscape; probably the road conforms closely to the final channel, and in part follows a bordering wall' (Green 1968, 34-35). This alignment can be traced westwards following the road through Newchurch to the natural channel of the Sedbrook Sewer south of Ruckinge. It is the easterly part of this channel and the walls associated with it that are of particular interest. The northerly wall mapped by Green passed through Stonebridge Field and this alignment can be traced further west following field boundaries to Newchurch, where Green observed 'a distinct change in level, noticeable in the road south of Oak Farm, does occur north of Newchurch, where the New Marshland is appreciably lower for about half a mile, mostly east of the point mentioned' (Green 1968, 36). Interestingly, this is close to the Wallsfoot Sewer, a name not without significance. Although traceable this alignment is not marked by distinct upstanding earthworks; it is detectable only as a very subtle variation in land levels. Similarly, south of Lower Wall the earthwork features in Nine Acres are also slight. These earthworks which must date from the late Saxon period are surprisingly modest when compared to the sustantial walls on Walland Marsh that date from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Embankments dating from the Saxon period are rare and often these early walls were destroyed by later rebuilding and improvements. The wall across Marshland in the Norfolk Fens is believed to be of late Saxon date although it was substantially rebuilt in the medieval period (Silvester 1988, 160, 164). The sea-wall protecting the Wentlooge Levels in Gwent from the Severn estuary was rebuilt in the sixteenth century after flooding, thus destroying any evidence of an earlier wall (Allen and Fulford 1986, 94). It is only because of the complex development of the Romney Marsh region with its shifting shingle banks and fickle water-courses and the subsequent centuries of pastoralism that traces of a possibly unique example of Saxon embanking have been inadvertently preserved. 90 EARTHWORKS SURVEY, ROMNEY MARSH CONCLUSION These earthwork surveys have shown that old pasture on Romney Marsh contains much important evidence about the past. Only detailed field survey can reveal the full complexity of the features in the landscape and their relationship with one another and the natural environment. Examples of ancient field systems that once covered much of the region have been recorded and examined in a wider context. It has also become apparent that, in places, the complete medieval landscape has been preserved providing a unique opportunity for research. Comparative study has enabled a suggested chronology to emerge. It is imperative that work of this kind continues before more valuable evidence is lost. The area of pasture on Romney Marsh is declining year by year. In 1940, 84 per cent of the Marsh was permanent pasture, by 1985 this figure had fallen to 32 per cent (Edwards 1987, 27). Today it is even lower and anyway only a small proportion of this permanent pasture is old pasture. Where old pasture survives on Romney Marsh today it is seriously at risk from ploughing and other development. As well as providing so much new local knowledge this research has other applications. Marginal areas have always been a useful barometer gauging wider economic trends. Thus, indirectly, the study of vulnerable local landscapes such as those of Romney Marsh can provide a valuable window on contemporary national trends and problems. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was undertaken as part of the research for a doctoral thesis funded by the British Academy. It was also supported by a small grant from the Romney Marsh Research Trust. Thanks are due to Miss Eleanor Vollans, Mark Gardiner and Tom Williamson. Jane Russell drew some of the figures. BIBLIOGRAPHY Allen and Fulford 1986 J.R.L. Allen and M.G. Fulford, 'The Wentlooge Level: a Romano-British reclamation in South-East Wales', Britannia, xvii (1986), 91-118. Brown and Taylor 1991 A.E. Brown and C.C. Taylor, Moated Sites in North Bedfordshire, Vaughan Paper no. 35, University of Leicester. Edwards 1987 A. Edwards, The Romney Marsh Story: A Study in Agricultural Change, FBU Occasional Paper no. 14 (Wye). Field 1972, 1989 J. Field, English Field Names. 91 Green 1968 Le Patourel and Roberts 1978 Neilson 1928 Reeves 1995 Silvester 1988 Smith 1943 Tatton-Brown 1988 Taylor 1975 Teichman-Derville 1936 Verhaeghe 1981 Ward 1936 Wass 1995 Wilson 1985 ANNE REEVES R.D. Green, The Soils of Romney Marsh, Soil Survey of Great Britain, Bulletin no. 4 (Harpenden). H.E.J. Le Patourel and B.K. Roberts, 'The significance of Moated Sites', in (Ed.) F.A. Aberg, Medieval Moated Sites, CBA Research Report no. 17. N. Neilson, The Cartulary and Terrier of the Priory of Bilsington, Kent. A. Reeves, 'Romney Marsh: the fieldwalking evidence', in (Ed.) J. Eddison, Romney Marsh: The Debatable Ground, OUCA Monograph no. 41. R.J. Silvester, The Fenland Project No. 3: Marshland and the Nar Valley, East Anglian Archaeology, Report no. 45. R.A.L. Smith, Canterbury Cathedral Priory. T. Tatton-Brown, 'The topography of the Walland Marsh area between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries', in (Eds.) J. Eddison and C. Green, Romney Marsh: Evolution, Occupation and Reclamation, 105-111. C.C. Taylor, Fields in the English Landscape. M. Teichman-Derville, The Level and Liberty of Romney Marsh (Ashford). F. Verhaeghe, 'Medieval moated sites in coastal Flanders', in (Eds.) F. Aberg and A. Brown, Medieval Moated Sites in North-West Europe, BAR International Series 121. G. Ward, 'The Wilmington Charter of A.D. 700', Arch. Cant., xlviii (1936), 11-28. M. Wass, 'The proposed northern course of the Rother: a sedimentological investigation', in (Ed.) J. Eddison, Romney Marsh: The Debatable Ground, OUCA Monograph no. 41. D. Wilson, Moated Sites. 92