Patterns of Inheritance and Attitudes to Women Revealed in Wills: the Tonbridge area 1500-1560

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

Lancastrian Loyalism in Kent during the Wars of the Roses

The Medway Megaliths in a European Context

Patterns of Inheritance and Attitudes to Women Revealed in Wills: the Tonbridge area 1500-1560

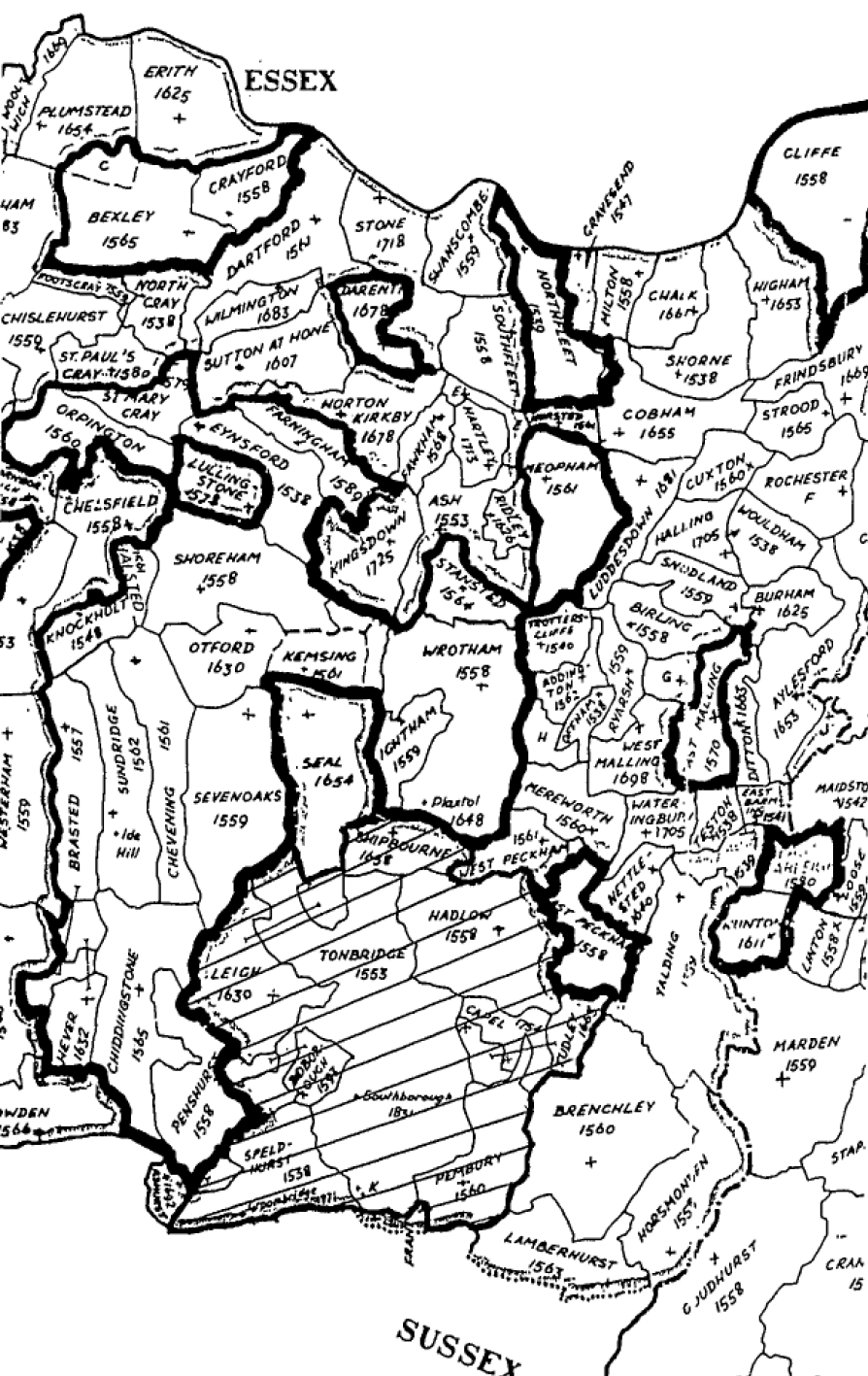

PATTERNS OF INHERITANCE AND ATTITUDES TO WOMEN REVEALED IN WILLS: THE TONBRIDGE AREA 1500-1560 ALISON M. A. WILLIAMS In 1560 Tonbridge was a small market town serving its surrounding parishes. This article is an extract from an original study which was designed to find what could be learned of Tonbridge and its contiguous parishes during the previous sixty years from the wills of the area recorded in the Will Registers of the Rochester diocese.1 The wills were always the main source although supplemented with evidence from the Tonbridge parish register of burials,2 beginning in 1547, Christopher Chalklin's study of Tonbridge 1550-17003 and various secondary authorities. The word 'will' is used here to describe a document which usually contains two parts; a testament which concerns the disposal of personal property, including the soul, and a will which describes the arrangements forthe disposal of land. The will was usually registered with the testament in the ecclesiastical court. However, since this court had no jurisdiction over land, it was only a matter of convenience, and 'the absence of a will does not necessarily mean the absence of land'.4 During the period 1500-1560 there are 458 wills recorded for the nine parishes studied, Tonbridge, Hadlow, Speldhurst, Tudeley, Capel, Pembury, Leigh, Shipbourne, and Bidborough (Fig. 1). Of these, Tonbridge and Hadlow dominate by their comparatively large number of wills while Bidborough, the smallest, has only eight (Table 1). Apart from a peak during the years 1555-1559, there is an average of six wills per year from the nine parishes together. Seventy of the wills are written either wholly or partly in Latin, and the majority of these date from before 1525. When both languages are used, the testament is in Latin while the will is in English. Sometimes the scribe's Latin failed him and such phrases as 'una swame de apibus' and 'unum paynted cloth' are fairly common. Over the period as a whole, one will was written by a woman for 245 ALISON M. A. WILLIAMS * . / /62S V fgInuHSiTAD . ( CLIFFC /SSt sroft k, men* */65S «

Ao*'+y

Fig. 1. Tonbridge and surrounding parishes

246

PATTERNS OF INHERITANCE AND ATTITUDES TO WOMEN IN TONBRIDGE WILLS

E

au.

SO

o

o\

o

Os

ro

OS