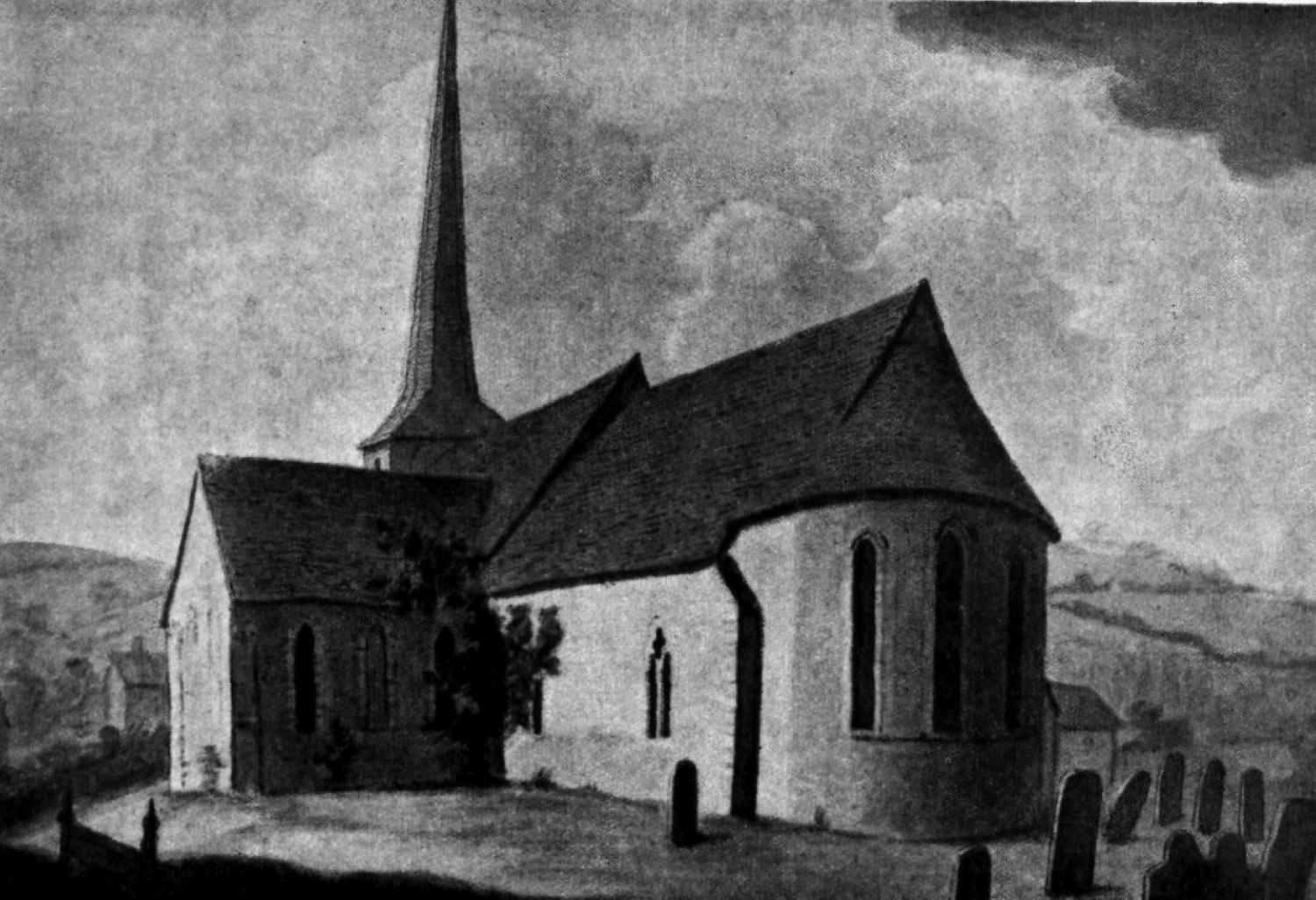

Eynsford Church in the Valley of the Darent

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

An Early Alteration of the Boundary between Kent and Surrey

The Plan of St Austin's Abbey, Canterbury

( 156 ) EYNSPORD CHURCH IN THE VALLEY OP THE DARENT BY GREVILE MALRIS LIVETT, B.A., E.S.A. THE beautUul vaUey of the Darent, running from south to north, has revealed evidence of occupation from pre-historic times onwards. Stone implements palseohthic and neolithic have been found here and there, and at Green Street Green there are tumuh of indeterminate date. The Roman period is marked at the upper end of the vaUey, where the river cuts its course through the chalk escarpment, by the remains near Otford station of a house of early date, a large courtyard near by, and a pottery kiln, with coins ranging from the first to the fourth century ; about Farningham, north of Eynsford, by coins of the same range, and remains of a house in Farningham wood ; a little south of Darenth, on the east bank of the river, by the famous remains of the so-caUed Darenth ViUa, excavated and described by Mr. George Payne in Arch. Cant., XXII (1896) and further examined by Mr. George Fox, who advanced a theory (Archceologia, LIX) that two early corridor houses were altered and buUdings added to form a fulUng estabUshment; and lastly at the northern end of the valley, by various minor discoveries in the town of Dartford and two cemeteries in its vicinity. At Eynsford, midway between Otford and Darenth, no structural remains have come to light, but a few Roman tUes occur in the masonry of the Norman Castle. It is not surprising that Anglo-Saxon remains are less prolific. Of course the place-names are significant of complete occupation at an early period. Eynsford affords an example appropriate to this paper. A dehghtful book by H.H.B. of Darentlea, entitled The Village of Eynsford, contains a note communicated to the author by Professor Skeat, EYNSFORD CHURCH. 157 who compares it with Eynsham (Egenesham, misspelt Egonesham in A.-S. Chron.) in Oxfordshire. The Professor explains that Aegenes is the genitive of Aegen, and that Aegensford, contracted into Eynsford, means Aegen's ford, Aegen being " a well-ascertained Anglo-Saxon name, though its meaning is unknown " ; and that " Aegen is pronounced Uke the ayon in bayonet." The river-name, Darent, which gave its name to Saxon Darenth and to Dartford (a contracted form of Darentford), contains a much older element, representing jfche British derventio (= oak river) ; but aU the other names of the vaUey seem to have had a Saxon origin. Of material remains a few discoveries of some importance have been made—see Arch. Journ., XXIV, and Vict. Co. Hist., Kent, Vols. I and II. Nearly forty graves of a cemetery found a Uttle north of Farningham station were opened in 1866 and the next year. Many of the burials are said to have been poorly furnished, and to have shown no sign of Christianity. In some the bodies lay north and south, which led the experts of the time to conclude that they were non-Christian, though " the date may have been after Christian times, perhaps as late as the 8th or 9th century." But pagan customs and superstitions continued to prevail among the people after their conversion to Christianity, and, moreover, the Christian custom of burial with feet to the east was not universaUy foUowed at a much later date, for when excavating the ruined chapel of Stone near Ospringe the present writer found north and south burials lying against its post-Conquest east and west waUs. A few years earUer (1860) a reUc of the early Anglo- Saxon period was found a Uttle north of LuUingstone—a bronze bowl, of which the ornamentation, according to Mr. Reginald Smith, F.S.A., is in part reminiscent of late Celtic work and in part is of a character that " may weU be due to Christian influence." A simUar bowl is said to have been found at Eynsford. The only monumental evidence known to me of Christianity in the vaUey is suppUed by the church of 158 EYNSFORD CHURCH. Darenth, built of materials quarried from the ruins of the Darenth Villa, in a style that betokens late-Saxon work.1 We now come to documentary evidence—first, with regard to properties denoted manors in the Exchequer Domesday, compUed in 1086. At that time the king held Dartford in demesne (i.e. in his own hands) ; the Archbishop held in demesne both Darenth and Otford ; whUe Knights of the Archbishop held of him Farningham and Eynsford. Otford had been given to the Church of Canterbury by King Offa in 791 (Dugd. Mon., i, 19) ; Darenth, by Duke EaduU in 940 (Decern Scriptores, 2220) ; and Eynsford by one iElphage in the time of Archbishop Dunstan (960-80).2 Hasted tells us that Archbishop Alphege gave Farningham to Christ Church in 1010. The Bishop of Rochester and the Canons of St. Andrew's were less fortunate: the only gUt I can trace, from this valley to St. Andrew's, is one of some land at Darenth bequeathed by the wiU of one Birtrick of Meopham, witnessed by iElstane, bishop of Rochester (946-84)—printed in Lambard's Perambulation, p. 540. The inference is that Christianity was becoming organized in this neighbourhood 1 In his Antiquities . . . in the Diocese of Rocliester (1788) John Thorpe gives a view of the ruins of Lullingsfame church, which he tells us stood by the wood about a quarter of a mile north of Lullingstone parkgate, built with flints and Roman bricks. I have not seen the ruinsj: possibly they may be remains of a Saxon church like Darenth. 2 The Textus Roffensis (c. 1120) preserves (Ed. Hearne, cap. 73) a story relating to the administration of the will made by iElphage in the presence of Archbishop Dunstan. The property consisted of lands at Crayford, Cray, Wouldham and Eynsford, which the testator divided into three parts, bequeathing one part to Christ Church, one to St. Andrew's, and one to his nephew's widow. The widow married again, and with her connivance the husband usurped the rights of St. Andrew's by retaining Wouldham in his own hands. Therefore the Archbishop summoned a court consisting of the bishops of London and Rochester, the canons of London and the monks of Christ Church and Rochester, with a host of magnates from four neighbouring counties (Sussex, Wessex, Middlesex and Essex), under the presidency of Wulf, the " shire man " or " judge of the county," and with books of ecclesiastical law, and with the sign of the cross of Christ held in his hand, the archbishop took an oath that the claim of St. Andrew's was valid. This was ratified in the same manner by the ten hundred magnates of the four counties aforesaid. The Manor of Wouldham fell to the share of St. Andrew's. EYNSFORD CHURCH, 159 in the tenth century, if not earUer ; and that the landowners, looking upon Canterbury rather than Rochester as their spiritual home, were aheady buUding churches, though the parochial system as we know it was not fuUy developed throughout the country untU two centuries later. Domesday Book mentions the existence of churches as foUows: at Horton [Khkby], " a church there " ; at Eynsford, " two churches " ; and, under Dartford, " The Bishop of Rochester holds the church of this manor: besides this there are stiU (adhuc) three chapels (cecclesiolce) there ". There is no mention of the church at Darenth, nor of any church at Otford, Shoreham, LuUingstone, Farningham or Sutton. The late Mr. WiUiam Page, F.S.A., in a valuable paper contributed to Archceologia, LXVI,1 remarks that, " the entries of churches in the Domesday Survey of Kent are meagre." The entries of those in Norfolk and Suffolk seem to be practicaUy complete, whUe the survey of Bedfordshhe and Bucks on the other hand makes mention of very few—five in the one and four in the other county, i.e. about 8 per cent. There was no fixed rule to guide the jurors of the different counties in this matter. It is inconceivable that, apart from Darenth and the D.B. churches of Dartford, Horton and Eynsford, there were no churches from Otford northwards in the pre-Conquest period stUl existing in 1086. Indeed Hasted, without giving his authority, says that " the church of Farningham" (not mentioned in D.B.) " seems to have been given to the church of Canterbury by archbishop Elphege in 1010." According to the Textus Roffensis the church of Sutton, with the chapels of Wilmington and Kingsdown (both on high ground one on each side of the vaUey) was given to the church of Rochester by Henry I. This may have been built after 1086, but possibly much earUer, though there are no indications of Saxon work in the existing buUding. It is noteworthy that in the time of Bishop ErnuU (1115-24), in aU the nine places mentioned above, and at Liillingstone in addition, there were churches 1 See also Tlie Domesday Inquest, by A. Ballard. 160 EYNSFORD CHURCH. that paid fees to theh mother-church of Rochester for holy chrism, the oil used in the rite of baptism.1 With regard in particular to Eynsford, the existing buUding, with which this paper is especially concerned, contains no material pointing to a church of a date earUer than the twelfth century, but it may weU stand on the site of an older church buUt of wood. In early times St. Martin of Tours, who died 397-400 and in whose name the church was dedicated, was a most popular Saint throughout Western Christendom and even further afield. Tradition says that St. Ninian, when he heard of Martin's death, was buUding at Withern in GaUoway a church which on completion he dedicated to his friend's memory (Plummer's Baeda, p. 128). The church of St. Martin, Canterbury, was buUt for Queen Bertha before the coming of St. Austin in 597. Other churches dedicated to the Saint in London, one on Ludgate HUl and the other in Upper Thames Street, probably date from early in the seventh century, and the foundation of St. Martin's-le-Grand may be equally early (Wheeler, in Antiquity, Sept., 1934, p. 298). An " oratory " of St. Martin, New Romney, was in existence in 740 (A.C., XIII, 238).2 At the time of the Domesday Survey the Manor of Eynsford (6 sulungs) was held of the archbishop by one Ralf, son of Unspac (or Hospicus). This famUy assumed the title " de Ainesford," and one of the de Eynsfords must have built the castle and doubtless the church also somewhere about the middle of the tweUth century.3 With regard to the " two churches " mentioned in D.B. reference may be made to an appendix to the Domesday Monachorum which records an inquiry held c. 1225, when the 1 The complete list of such churches in the diocese, written about 1120, but evidently copied with some alterations from an earlier list, appears in Textus Roffensis, beginning on folio 220b. It is printed in Hearne's edition, cap. 213. 2 The story of St. Martin, when a young soldier, dividing his cloak to share it with a shivering beggar is too well known to mention, except to suggest it as a subject for illustration to any benefactor who may wish to fill a window in the church with stained glass. 3 Dr. Gordon Ward thinks that the castle may have been one of the adulterine castles built in the reign of Stephen. The Norman church may be dated a little later than the castle. Inset shingled jpire i^^i ~ riat roof ./ .-. ti The frame of this roof Is hidden by a circular ceih/tg of which a small portion ha been cut Qway to expose a rafter. Probably it is an example at the scvtn-sidtd rafter roof, that comprises two upright struts supporting a pair of rafters and tvo diagonal ties under a collar beam, with the addition of a circular ceiling, as shewn in section in an inset over the porch, c/. c\»irR^ i AXIAI. fiFCTION A N Fl FVATION OF ST KATHARINE l HP m^h PORCH —TOWER CHANCE site oj a newel stairco fforman rtfaced SOUTH TRANSEPT PERIOD PLAIN Norman Early E n a 1 is h Dec THE. CHAPEL OF S:JOHN BAPTIST mum,*! iiiiiiiim Arch. Cantx §Jil. mens, el del. ign-. EYNSFORD CHURCH. 161 de Ainsefords were stUl in possession, whereby it was found that the church of St. Martin with the chapels of Stanes and Frenigeham had been granted of old to Canterbury. Stanes may be LuUingstone, and Frenigeham is certainly Farningham ; and it seems likely that this chapel of Farningham was the second of the two D.B. churches of Eynsford. In D.B. Farningham is not quoted as a manor : it seems to have been the name of several smaU properties held of different owners.1 THE ARCHITECTURE OP THE CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF ITS PLAN. The accompanying plan shows that the church of Eynsford consists of a nave measuring, inside, 45 feet in length by 27 in width ; a choir, 30£ by 25 ; a south transept, 21 by 20, annexed to the eastern haU of the nave ; a north aisle, 30 by 16, separated from the nave by an arcade of two arches that spring from a central column and two responds, and divided into two unequal parts that are covered by ridge-roofs running transeptwise at right angles to the naveroof ; a choir terminating in a semi-circular apse, 16 feet wide ; a west tower, buUt with its axis to the north of that of the nave, with diagonal buttresses encroaching upon the nave, and an entrance annexed to its western face and protected by a porch. Total outside, 133 by 81 feet. The nucleus of this comphcated building, the original Norman church, seems to have been an example of a comparatively rare type known as tripartite or three-celled. In the plan the parts of the Norman buUding that stUl remain are shown in fuU black, whUe the parts that have been destroyed are indicated by a Ught tint. AU subsequent alterations or additions are indicated by appropriate kinds of shading so far as they stiU exist, and by different tints for the parts which have been destroyed. The writer hopes 1 One suiting held of the Abp. by Ansgot (D.B.), and later (D.M.) by the monks of Ch. Ch.; J sulung held by Wadard of the Bp, of Bayeux, and later of the Bp. of Rochester; 3 yokes held by Ernulf of the Bp. of Bayeux and later (D.M.) of the Bp. of Rochester; and i yoke held of the Bp. of Rochester by Malgir (D.M.). 14 1 6 2 EYNSFORD CHURCH. that readers who are interested in the evolution of mediaeval church planning may be enabled by a study of the plan, with the further help of the photographs, to appreciate this interesting buUding even though they may not find opportunity to visit it. I t is weU known that our larger churches of Norman foundation, both conventual and coUegiate, ended eastwards in one or more apses. The smaller churches were usuaUy square-ended. Departures from the usual type, which consists of an aisleless rectangular nave and a smaU squareended chancel or sanctuary, occur here and there in a group of neighbouring churches. At Maplescombe, a mUe and a haU S.E. of Eynsford, there is a most interesting ruin of an early-Norman single-ceUed apsidal church. That apse may have been suggested by Saxon Darenth, of which the chancel must, in my opinion, have ended in an apse, forming a twoceUed church.1 And the apse of Darenth, again, may have influenced the buUder of the Norman church at Eynsford. The existing church, U stripped of its tower, transept and north aisle, shows a typical three-celled buUding : but the apse is Early English, and thhteenth-century apses are so rare (the only case I remember is that of the ending of the side chapels of St. Mary, GuUdford) that one is led to consider the possibihty that it replaced a smaUer sanctuary of the same shape. 1 The accompanying plan of Darenth is based in part upon plans of parts of the church kindly sent to me by Mr. W. D. Caroe, and in part upon plans of our member Mr. Elliston-Erwood, F.S.A., in a paper published in 1912 in the Proceedings of the Woolwich Antiquarian Soc. There is no doubt about the lines of the Saxon nave, of which much still exists, but the original chancel has disappeared. Mr. Erwood's restoration of it is indicated in my plan by dotted lines. In my opinion so short a chancel does not account for the unusually great length of the existing Norman chancel which replaced it. To meet this need I have indicated one that comprises a square choir terminating in an apse, the proportions of which tally with those of the chancel of late-Saxon Worth in Sussex. My friend, Mr. P. M. Johnston, F.S.A,, who described the church on the occasion of the Summer Meeting this year, to whom I sent my plan, agrees with me, but he suggests that the apse may have been ovoid in form, like that of Rochester (604) and those which he has discovered at Stoke d'Abemon and Fetcham in Surrey. I have therefore added to my plan an indication by broken lines of such an apse. Mr. Johnston also gives reasons for " putting the Darenth Saxon church in an early group, say A.D. 700-800". It is hoped that Mr. Johnston will find time to elaborate his ideas in a paper for publication in the next volume of Arch. Oant. S.W. View. [Payne Jenkins. A.C. XLVI. S.E. View. EYNSFORD CHURCH. [Payne Jenkins. PLATE 1. EYNSFORD CHURCH. 163 The only parts of the Norman church that remain visible are in the south waU of the nave and of the chancel, and perhaps a quoin of the chancel-arch on which the south respond of the existing arch is based (indicated on the plan by an arrow). The flint-work, roughly-coursed with a suspicion of herringbone, proclaims the Norman origin of the na»ve-waU, somewhat marred, however, by the glaring modern renewal of the stonework of its inserted Tudor windows. The S.W. quoin, where the waU turned to form the west waU of the nave, has unfortunately been destroyed k MOR.MAM CHOIH 4 a c W K n i M I ' X HllllllllllllflHIIIllllllMllllllllllMHIII «l SAXON DA/\EMTH NORMAN conject- si-i/ra tM.CW EYNSFOhlD A.C. XLVI. and the end of the wall cut back with an upward slope, exposing its core. (This was done when the vice that afforded ascent to the second stage of the tower was demolished, a ladder inside the tower being substituted for it.) AU the other original quoins also have been demolished, but there is reason to beUeve that the material of which they were composed was Caen-stone, and that some of it was used again by the Early EngUsh builders in theh apse. Remains of two smaU round-headed windows, seen in the chancel high up in the south waU, prove that that wall also is Norman, but externaUy it has lost its original face. 164 EYNSFORD CHURCH. The S.E. quoin is modern work in Bath-stone. The lines of the destroyed walls of the Norman church wUl be discussed in due course. The first enlargement converted the three-ceUed buUding into a crucUorm church by the addition of a transept annexed to the eastern haU of each side of the nave. The existence and disappearance of the north transept wiU be discussed later. A flight of four steps under a wide and lofty pointed arch gives access to the south transept. OriginaUy there was only one step, the floor of the nave having been lowered in modern times by about a foot, and that of the transept, judged by the height of the sedUe, raised by haU a foot. The arch has a flat soffit that is edged with chamfered wrought-stone voussoirs and rises from a square impost hoUow-chamfered. The edges of the square responds are moulded into a pointed bowteU. This pointed arris rises up into the necking and beU of the capitals and so runs up to coincide with the square edge of the impost; and it runs down into the bases, which consist of two rounds with an intervening hoUow, aU showing the same arris. AU this, iUustrated by sections (A, 1-6) in the plate of mouldings, is extremely rude and early in character. A competent authority has suggested for it the date 1180-90 ; but the section of the string-course (A, 7) that runs along the side and end of the transept, and from which there rise the sharply-sloping sUls of large lancet windows, is of a more advanced character, approximating to that of the next stage of the Early EngUsh enlargement. I am inclined, therefore, to put the date of the transept somewhere round about 1200. In the end waU there is a wide sedUe with a depressed pointed arch and chamfered edges that show a normal E.E. stop ; and beside it a piscina, simUarly plain but having a fluted basin Uke that of a piscina in the later work of the E.E. apse. The successive enlargements, as we shaU see, have features that approximate them to one another, each period showing some influence of its predecessor. The next enlargement may be dated in the second or third decade of the thhteenth century. It consists of the : • J ,1 "N * i | i | • • - » •! mSmmSSIW . , _ » . M ./'.'" * *r East View. [Payne Jenkins. AC. XLVI. North Side of Choir and Apse. EYNSFORD CHURCH. [Payne Jenkins. PLATE 2. EYNSFORD CHURCH. 165 ereotion of a chapel on the north side of the chancel, succeeded after an interval by the rebuUding of the apse on a larger scale than the original Norman apse. The buUding of the chapel mvolved the destruction of the north waU of the Norman church. The line of that waU, as shown in the plan, about 2 feet within that of the nave-waU continued eastwards, is deduced from the relative fines of the corresponding Norman walls on the south side. The E.E. buUders did not adopt the usual method of inserting the arcade of communication between theh new chapel and the chancel in the Norman waU : they buUt it in a new waU, continuing the Une of the nave-waU eastwards, with a sUght southerly divergence corresponding with that of the waU they destroyed. This chapel must have been a buUding of considerable size, covered by a ridge-roof and running the whole length of the chancel, but its width is not known : the Une of its north waU adopted in the plan is conjectural— probing, which might test it, is made difficult by the presence of graves. About 150 years ago two stone coffins were found in the area of the chapel: at a later date they were disinterred and placed in the chancel; and finaUy they were removed to the porch, where they now rest. The ereotion of a chapel in this position would be abnormal in the evolution of church-planning unless there were some buUding to the west of it, on the north side of the nave. The idea of a contemporary aisle, which normaUy would run the whole length of the nave, seems to be excluded by the absence of any indications of such an addition. The suggested south transept would meet the case. An arch inserted in its east waU would form communication with the new ohapel. The existing short aisle is whoUy work of the Tudor period. Its buUders destroyed both the transept and the ohapel. They blooked the arcade of the ohapel, fortunately leaving remains of its arohes and responds, whioh are visible outside as woU as inside. In the blocking wall they made under each aroh a window. They preserved and ro-uaod tho rere-arohes of the destroyed ohapel, but they encased the glazing with stone-work of theh own period's 166 EYNSFORD CHURCH. style. (AU this is clearly iUustrated in the elevation above the Period-plan on the first folding Plate.) The mouldings of the rere-arches deserve special attention. They show some affinity to those of the transept aroh. That of the arch (B 1) has a pointed bowteU (which may be compared with A 6); and the abacus of the capitals (shown in plan in B 1 and in section at B 2) runs on some inches along the waU-face on either side like that of the transept arch. The capitals and bases (B 2, 3) are primitive for E.E. work—e.g., above the necking of the cap., instead of the usual beU there is a plain round, seen in the section as a vertical Une, instead of a curving hoUow. On the other hand, the mouldings of the arches of the arcade and theh label are practicaUy identical with those of the lancet-windows of the apse (cf. C and D). Thus there is a striking contrast, difficult to explain, between the design and execution of the arches of the arcade and those of the windows under them. No doubt the waUs of the chapel with their windows were completed before the waU of the chancel was dealt with, and there may have been a delay of some years in the meantime. The replacement of the north waU of the Norman chancel by the new arcade buUt just outside it widened the choir and left the apse and altar in a lopsided position, nearer to the south than to the north side. To restore the altar to a central position, on the axis of the chancel thus enlarged, involved the erection of a wider apse in place of the old one. An important feature of the apse is the quoin that rises on either side to the waU-plate at a height of about 19 feet. Three stones near the bottom on the north side and one on the south are fragments of decorated Norman work. Of the rest aU but a few blocks of chalk are of Caenstone ashlar, faced with the diagonal axe-tooling characteristics of Norman work. (See figs. 3 and 5, Plate 3.) The stone carved in a chessboard diaper-pattern must have come from the tympanum of some doorway that has been destroyed. The others may have come from the destroyed Norman apsearch. That on the south side (fig. 5) shows a fragment of an impost much Uke one of the imposts of the Norman west ffi N . E . V I EW A.C. XLVI. F.q.4 EYNSFORD CHURCH. PLATE 3. EYNSFORD CHURCH. 167 door—a diamond diaper-pattern on the face above a double billet. AU are incomplete and mutUated by a chamfer cut by the Early EngUsh buUders of the apse. The remaining two (fig. 3) are similarly mutUated : the lower one shows a row of pearls in a series of connected narrow vesica-shaped mouldings. About 5 feet above the floor on the south side there projects from the quoin another Norman fragment (fig. 5), measuring 5 by 8 inches, evidently cut from an impost of the destroyed apse-arch. In it there is a vertical hole in which, U one inserts a finger, one feels that the front surface has been abraded at top and bottom, evidently by a cord or rope pulled up and down through i t : the inference is that it served for the rope by which in mediaeval times the Lenten veU was drawn. On the same side there is a trefoU-arched piscina (PI. M, Section E) with fluted basin, and the apse is Ughted by three lancet-windows the rere-arches of which have banded shafts and their sloping sUls rise from a stringcourse which runs just beyond the two outer arches (M, Section D). The exterior of the apse-waU has been extensively refaced and the dressings of the lancets renewed in Bath-stone. The construction of the modern roofs is hidden, and owing to the difficulty of obtaining accurate measurements I have drawn it only conjecturaUy in the section. In the plan the rafters of the semi-dome are indicated in dotted lines. The next stage of the thhteenth century alterations and additions to the Norman church comprises the buUding of the existing chancel-arch and the west tower, which was foUowed closely by that of the porch. The chancel-arch is an example of the custom that prevaUed in the thhteenth century of replacing a Norman arch by one wider and taUer. The method adopted here was designed to bring it into axial Une with the widened chancel and apse, leaving it a Uttle to the north of the axial Une of the nave. (The axial lines are shown in the plan.) There is some indication that this was effected by setting its northern respond back some 2 feet or more from the position occupied by the Norman respond. The floors of the church, like the site on which it stands, slope 168 EYNSFORD CHURCH. from east to west; but from time to time, when new floors have been laid down the levels have been altered. There is now an ascent of four steps (2 feet) from the nave up to the chancel. The bases of the responds are 3 feet 3 inches above the chancel floor. They stand on square plinths and rise fuUy 5 feet above the present nave-floor. On the south side that phnth shows a quoin of axe-faced stones (marked with an arrow in the plan), the remains probably of the outer order of the respond of the original Norman arch. This is 7' 6" from the S.E. angle of the nave: the north respond of the Norman arch would be about the same distance from the opposite angle. The arch was widened northwards to bring it into line with the sanctuary and its altar. Its mouldings suggest a date late in the thirteenth century. The label has a flat face, rounded above and plain-chamfered below (PI. M, fig. El). As seen from the nave its northern end is rounded KEY TO PLATE OF MOULDINGS. A. South Transept :— impost (1), bell of capital (2), angle-shaft (3), base (4), plinth (5), section of shaft and plan of base (6), string all round under windows (7). B. Choir, N. side, window :— rere-arch (1), cap. and base (2, 3). C. Ditto, blocked arcade : label (1), exposed part of arch (2). D. Apse windows :— label and arch (la, b), capitals (2a, b), shaft-bands (3a, b), baBes (4a, b), string under windows (5). E. Apse piscina :— capitals and base (la, b, and 2), label and arch (3a, b), section of jamb (4). F. Chancel arch :— label (1), cap. and base (2, 3). G. Porch :— label (1), upper order of arch (2). H. Aisle arcade :— capital (1), base of responds (2a), base of free column (2b). J. Ditto, arches :— Tudor stones, Kentish-rag (2), older stones, ? Reigate stone reused (1). K. Tower arch :— (Kl) Early English soffit: (a) exposed ; (b) covered by the Tudor order (K2). / ' / / ' "/ 777777T7 EYNSFORD CHURCH ////'J, Ufa IT ^JQce zdgtof capital /;//>>/ sOgToj PLATE 'M' of M0ULDING5 soffii \\\.\\w.\\\n\\\\\\\\\\\\\n\\\\\\y.*\\\\\. '"SS*. **ff& °f forty &»$f- oi-ci ^ \ \ \ % \ \ \ \ \ » N \ < \ w \ ^ i \ m ^ pi tilthand vsatl-fuce. *Sest*rard' Tudor a scale of inches »wv\\ I soffit muBfajfafta iuai l e-dgi ( of capital. tdmaftor&tl 9(1 J" X3T Plan A.C. Vol. XLVI. G.M.L-103^-- EYNSFORD CHURCH. 169 and its southern has a head which has its inner side paired away to make it fit its position (PI. 4, fig. 4). The capital shows a scroll-moulding with a smaU round under it (PI. M, fig. F2), and the chamfered edge of the respond has a daggerstop— both typical of the Decorated style. It has been assigned to a date about 1280-90 ; but I cannot think that the E.E, buUders waited so long before bringing their arch into Une with the sanctuary. Moreover the scroU-moulding was in use somewhat earUer : it occurs in the north transept of Rochester Cathedral as early as 1250. The base of the north respond is a ' restoration' ; that on the south side is original, and its section (PI. M, fig. E3) is suggestive of the early years of transition from E.E. to Decorated work. Another important feature is the pecuhar jointing of the voussohs of the inferior order : as seen in the section there is an alternation (though not quite regular) of broad and narrow stones, somewhat after the manner (in appearance, but not in construction) of what in Saxon architecture is known as ' long and short' work—a pecuUarity which the reader is asked to keep in mind. In the third course above the capital there is evidence (as may be seen in the elevation) of a hole that has been blocked. It must have housed the beam that crossed the arch at that height, carrying the rood or crucifix. The capital below it shows indications of mutilation and simUar repair, and from the fourth course below the capital there stiU projects a bracket which, Uke its feUow on the opposite respond, is decorated with fohage (PI. 3, fig. 1) carved in the style of the fifteenth century. AU these features are connected with the screen, and possibly a rood loft, that with the rood was removed at the time of the Reformation. Perhaps Mr. Aymer VaUance could deduce from them a reconstruction. It only remains here to mention a piscina in the navewaU near the S.E. angle, and the hagioscope near by in the chancel-arch waU. An altar once stood under t h a t ' squint.' We now come to the west tower. This, too, was planned with its axis to tbe north of that of the nave, so that entering by the west door (the only entrance to the nave) and passing 15 170 EYNSFORD CHURCH. under the tower-arch one looks straight through the chancelarch on to the sanctuary and its altar. Its east waU rises up above the west wall of the nave, thinner by 4 or 5 inches than its other three walls ; and its eastern angles are strengthened by irregularly shaped diagonal buttresses which, as I have said, obtrude themselves into the area of the nave. The tower-arch affords a sure clue to its thirteenth-century date. The front of the arch springs from corbels of Tudor or late Perpendicular design and the arch-mouldings present pecuhar features which are reproduced in the Tudor arcade of the north aisle and wUl be described later. As seen from the nave, therefore, this arch would seem to be entirely a work of the Tudor period; but in reahty this Tudor work was built within and on the soffit of an older arch, which may be examined behind it. The masonry of the older work correlates it with the ' long and short' work of the chancelarch. The same workmen, cut and faced the voussoirs of both arches; and the date of one cannot be far removed from that of the other. In the tower-arch the technique is obscured in some degree by a wooden screen (omitted in the elevation). It starts at a height of about 4 feet above the springing and is continued up to the apex. On the south respond at the height of 7 feet from the ground there are sUght remains of the old impost. Below that level on both sides the quoins were renewed by the Tudor buUders in large blocks of Kentish rag, faced with a ' point' and drafted with a chisel on the edges. The face of the waU beyond is plastered. The material of the older work seems to be ' firestone,' from the Upper Greensand formation, a characteristic Early English material. (A section of the composite arch is shown at K in the Plate of Mouldings.) The form of the western buttresses of the tower is remarkable. It seems to have been prompted by a desire on the part of the buUders to give breadth and dignity to the west front. To the 30-feet front of the tower and its buttresses they annexed a gabled wall, 16 feet wide and 3£ feet thick, in which they rebtdlt the Norman doorcase which they had removed from the west end of the nave-. Fig. 1. Fie. 2. Fig. 3. • I — • • Fig. 8. A.C. XLVI. EYN.SFORD CHURCH. PLATE 4. EYNSFORD CHURCH. 171 The effect was somewhat marred when, only a little later, they added the porch—to reahze it the reader should cover the porch in the plan with a sheet of paper. The breadth of the porch is the same as that of the annexe. Straight joists, seen outside, more distinctly on the north than on the south, show the junction of the two works. There can be no doubt that this porch is a work of the Early English period : the label of its entrance-arch shows a section (G2) that is practicaUy the same as that of the label of the E.E. chapelarcade (Cl) and the apse-windows (Dl); though that of the outer order of the arch, both inside and outside, having a rather flat hollow between the rounds, suggests a late date in the period. This supports our previous conclusion that the tower, which must have been earUer, if only a little earUer, than the porch, is also an Early EngUsh work. There is Uttle further evidence of such a date, for it is masked by later alterations, repahs, and perhaps some rebuilding, aU rather puzzling. Above the porch there is a window the square label of which is undoubtedly Perpendicular in section. An inset in the elevation shows its peculiar construction as seen from the inside above the ringing-floor. The same stage, in the south waU and near the S.E. corner, has a doorway with square head formed by a wooden lintel, Uke the lintels of the Tudor windows of the nave. This door formed the entrance from the destroyed newel-staircase. On the outside a jamb of this blocked entrance is visible. The exterior of the tower is not divided into stages by any external string-course, but rmmediately above the window over the porch-roof a head projects from the face of the waU, and just above that again a horizontal Une in the rubble face crosses the tower. It runs on along the two sides, and may be detected in the N.E. view, Plate 3. Above it may be seen one of the three windows that Ught the beUry stage. At a cursory glance that window might be taken for an Early EngUsh lancet, but on closer examination it is reaUzed that the pointed head is formed of two stones that must have come from the tracery of some demolished Perpendicular window. Similarly 172 EYNSFORD CHURCH. worked stones form the rere-arch, as seen from the inside. The section of the corresponding lancet in the west wall shows how they were used.1 As seen in the section and the photograph, the east waU contains two oval-shaped windows, buUt of brick, one on either side of the roof of the nave. The beUry stage seems to have been to a great extent refaced. It is capped by an elegant sphe, new shingled in 1728. In the ground-floor stage the entrance to the destroyed vice remains, converted into a sort of cupboard. A modern window has been inserted in the north waU. In the west waU a four-centred Tudor arch connects with a depressed pointed arch constructed by the E.E. buUders of the annexe that contains the Norman door-case. Before leaving the tower we may caU attention to the heads, no less than five in number, which appear on the face of its walls in odd places. Three of them are iUustrated in Plate 4 (in which the figures marked G are from photographs by Charlton of Canterbury, those marked J by Payne Jenkins of Tunbridge WeUs). Figures 2 and 5 may be seen in the photograph of the west end of the nave : fig. 2 on the diagonal buttress, has a crown on closely-fitting plaited hair ; fig. 5, higher up on the face of the tower, a winged figure with abundant curly hair and hands raised with palms outward. Fig. 1 is one of a pair on the inner face of the west waU. The fifth head on the tower, above the ridge of the porchroof, has aheady been mentioned. Fig. 7 is one of a pah on the face of the porch beside the ends of the label of the arch, both much mutUated, and in treatment not unlike fig. 4: as aheady mentioned, it forms one end of the label of the chancel-arch. Of the heads elsewhere in the church, fig. 3, which rivals No. 5 in beauty, appears above the apex of the central lancet in the end-waU of the transept. Fig. 6, which perhaps represents a hooded nun,.is indicated in the elevation above the capital of the free column of the north 1 P.S. The " puzzle " of the repairs desoribed in the text may be resolved in some respects by a suggestion that the Tudor builders replaced decayed ' firestone ' of the E.E. lancets of the belfry stage by bits of the tracery of fourteenth or fifteenth-century windows which had been inserted in the early transept or chapel demolished when they built their north aisle. A.C. XLVI. NORMAN DOORCASE, EYNSFORD. PLATE 5. EYNSFORD CHURCH. 173 arcade. In the aisle, on the other side of the capital, fig. 8. with its plaited locks and moustache-like f oUage flowing out of the corners of the mouth, is one of a pair of corbels that support the beam from which the rafters of the aisle-roofs rise. This is a Tudor head, but I cannot speak with confidence of the dates of the others. I am inclined to attribute 2 and 6 to the tweUth century, 4 and 7 to the thhteenth, and 5 to the fifteenth. Perhaps some member of our Society who knows more of this kind of sculpture than I can pretend to wUl contribute to a later volume of Arch. Cant, a note on aU the twelve heads. I must add that the presentation of the heads in the Plate does not show theh actual relative size. There is no evidence of any development of the plan in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. But the south wall of the transept contains two two-Ught windows (see S.E. view, PL 1) that were inserted at dates not far removed from one another. The narrower and taUer, at the west end, was inserted with a double purpose—to give Ught to the minister saying his daily office and to provide for the hearing of confessions of persons standing outside. The lower part is divided from the upper by a cusped transom and opens inwards on hinges. It serves the purpose of the ' low-side ' window found in the same position in so many churches. Mr. P. M. Johnston teUs me that the Franciscan Friars were often licensed to enter parish churches to hear confessions in this way. The buUding of the north aisle and its arcade was the last stage in the evolution of the plan. It must be assigned to a date, somewhere round 1500, in the Tudor period. Its division into two unequal parts with transeptal roofs is remarkable. (See N.E. view, PL 3.) Perhaps a reason for this inequahty may be suggested : it was necessary to run the guUy between the two roofs across the aisle in Une with the free column of the arcade; but to make the western • portion of the same width as the eastern would have left no room for the window in the nave-waU beyond. The stonework of that window, together with that of the two in the 174 EYNSFORD CHURCH. aisle and the two on the south side of the nave, has recently undergone necessary renewal: one can only wish that on the outside it had been given a less glaring appearance— could it not be toned down in some way so that it would harmonize more nearly with the surrounding waUs ? The very plain form of the capitals of the octagonal column of the arcade and the semi-octagonal responds is due to the refractory. nature of the material from which they were cut—Kentish rag. They stiU retain signs of the blue paint with which they were covered. In the arches we have a repetition of the pecuharity which appears in the towerarch. A section is indicated on the plan, and on a large scale (J) in the sheet of mouldings (Plate M). The long voussohs of the inferior order are cut in Kentish rag, but the smaU voussohs of the upper order behind it seem to be ' firestone,' from which it may be inferred that it was obtained from the E .E. buUding on the site. In adopting this pecuUar section for the arches it is evident that the buUder intended them to be fiUed with ' lunettes,' or painted boarding ; and it is probable that the whole arcade was fiUed with screens separating the aisle from the nave. In the east waU there is a doorway which shows a double ogee moulding on the outside. On the inside between the north waU and the steps that now rise up to the doorway there is room for the altar of St. Katharine that stood there in mediaeval times. It is proposed to furnish this end of the aisle for a ' children's corner'. The roofs of the church may be dealt with briefly. That of the chancel is an example of the " seven-sided rafter roof" (Francis Bond, Engl. Goth. Arch., p. 560). This land of frame had a long Ufe from the thhteenth century onwards. It is shown, with the addition of a semi-circular ceiling, in the inset on the elevation. H.H.B. in his book records that " the church was ceUd and the gaUery built in 1736." This must be the date of the circular ceUing of the nave, but it may be that it was only a renewal of an earUer ceiUng, for there is some indication over the chancel-arch that the chancel-roof was at one time simUarly ceUed. An A.C. XLVT EYNSFORD CHURCH. From Petrie's water-colour sketch. PLATE 6. EYNSFORD CHURCH. 175 expert authority has assigned the chancel-roof to a date 1350-1400 ; that of the nave to the fifteenth century ; and that of the aisle to the Tudor period. I venture to think that the chancel-roof must have been buUt in the Tudor period when the side-chapel was demohshed; and that the naveroof replaced the original one at the same time. The roofs of the aisle are similar in construction, except that they have curved braces rising from the wall-plates—a pretty design. The ceiling of the south transept with its ugly heads must be later than 1788, for in that year John Thorpe wrote, in his Antiquities in Kent, " the timbers of the roof are chcular but not ceiled with plaster." The same writer teUs us that " the large arch of entrance was fiUed up from the crown to the spring of it. . . . the three windows in the south end and the middle one in the east waU were blocked, and the whole buUding was vUely neglected and going to ruin." Petrie's water colour (Plate 6) of the exterior, painted between 1797 and 1813, shows that middle window stiU blocked, but indicates the joints of the stonework of the other two. The exterior stonework of aU the windows is now covered with a hideous ' Roman' cement and caUs for renewal, as do the sadly decayed quoins of the buttresses. The clearing out of lumber in the transept must have been done before Glynne visited the church somewhere between 1829 and 1840, but it was stiU waUed off from the church. He also speaks of " a chcle in the gable " as being waUed up. In this transept, covered by the organ, Ue the ledger stones of the Bosvile famUy, who succeeded the SibiUs as owners of Littlemote towards the end of Queen EUzabeth's reign.1 This is not the place for remarks upon the history of families who may have built or occupied the side-chapels in mediaeval times, but mention may be made of a lost epitaph that was formerly 1 The inscriptions are recorded in the Registrum JRqffense, p. 785. It has been suggested that the organ should be removed and the transept furnished for daily service. The western arch of the chancel-arcade could be opened and a chamber for both organ and vestry built outside along the east end of the aisle. The arch affords ample room for the front of the organ. 176 EYNSFORD CHURCH. in the north aisle. According to Weever it was " engraven in a wondrous antique character—Ici gis . . . la famine de la Boberg de Eckisford." The late Canon Scott Robertson revised it to run as Ici gist . . . la femme de Robert de Eckisford, and Thorpe suggested that Eckisford was a misreading by Weever of Einesford. Hasted says the de Eynsfords held the manor and castle until the reign of King John. A WiUiam de Einesford witnessed a grant by Henry III to the abbot and monks of Bee of a new clearing in theh manor of Weedon (Hist. MSS. Com., 9th Report, 353). I have been unable to find out the exact date and detaUs of the general repair of the church, but Scott Robertson, in his interesting paper read on the occasion of the Society's visit in 1884 (H.C., XVI), spoke of it as having been carried out " a few years ago," and we learn from a Beturn to the House of Lords that the sum of £1,150 was spent upon it between 1840 and 1874, the date of the Return. It involved the demolition of the gaUery (stUl existing in Glynne's time), the lowering of the nave-floor, and much work on the chancel, including doubtless the ref acing of the exterior of the apse and the rebuilding of its roof to a higher pitch than that shown in Petrie's interesting sketch. This paper would not be complete without some description, assisted by the accompanying photograph (PL 5), of the beautUul Norman doorcase. In its present position it is quite evident that it was a reconstruction. Scott Robertson suggested that in its original position it formed the chancel-arch. It is only about 6 feet wide—far too small in both width and height for that arch, which must have been about 12 feet wide, and the apse-arch stiU wider. Its size would suit that of the west doorway of the Norman church, and its removal thence by the E.E. buUders to its present position has a paraUel, as Mr. P. M. Johnston reminds me, in the church of Bredgar, where the tower from its foundations upwards was added in the fifteenth century. In the reconstruction the E.E. buUders erected the jambs about 6 inches too far apart. This demanded an arch wider in span than the original one, and one therefore for EYNSFORD CHURCH. 177 which the re-used tympanum upon the old wooden lintel was too smaU to serve as a centreing for its re-erection. A suitable centreing was formed round the tympanum by a thick layer of mortar on which the voussohs of the inferior order were assembled. The ring thus formed served as centreing for the superior order. But in each case, though the new arch was shghtly depressed in contour, the number of old voussohs was insufficient, and to complete it an additional smaU stone, rudely moulded, was sUpped in near the crown of each order. These features are evident to anyone who closely examines the arch. Possibly one or two others of the existing voussohs were newly cut, but it is difficult to decide the point. Very evident, however, is the large flint which serves for a voussoir to the outer order. The tympanum was originaUy composed of four courses of stones decorated with a chessboard pattern, but several of those in the second and third course have been replaced by a panel bearing an inscription which is obhterated. The pattern is similar to that shown in PL 3, fig. 3, but it is sfightly larger, indicating that the stone in the north quoin of the apse cannot have"come from this tympanum. The southern jamb-shaft is composed of several drums enriched with a sphal moulding that had been carved on the bench and were re-erected so that the ornament fits over the joints with fair accuracy, except in one or two instances. The original base, however, is missing, replaced by bricks. This shaft has a scoUop capital, and the impost is enriched on the face with diamond ornament under which there is a double bUlet-moulding. The carved fragment shown in PL 3, fig. 5, is a mutUated example of a simUar design, differing only in its reversed arrangement of the diamond ornament. The capital of the northern jamb-shaft is Uke its feUdw, but the impost is differently carved, showing a rude and irregularly-carved hatchet-ornament above a rope-moulding. The shaft is adorned with a chevron-moulding, the shorter stones with a single chevron, two longer stones with what may be described as a chevron and a haU, one of them being 16 178 EYNSFORD CHURCH. the lowest stone, and the stone above the lowest is spiraUy carved. The refitting of the drums on this side was not quite so successful as on the other side. I am doubtful about the date of the pointed arch inserted within the jambs of the Norman doorcase. The material is Kentish rag, and its hoUow chamfer has dagger stops. It was inserted to support the wooden Untel, possibly in the fourteenth century. An early Perpendicular font, also of Kentish rag, stands at the west end of the nave. The bowl is octagonal in shape, with fluted sides that are ornamented with carving : on the east side an archbishop's paU; on the west, a cross with a crown of thorns; on the south, a tau-cross; and single roses on the other sides. In conclusion I have to express sincere thanks to many persons : especiaUy to Mr. H. W. WeUard and his son for measurements taken on several occasions not only in this church but also at Darenth; to Lady Fountain and Mr. C. C. WinmiU for simUar help; to Mr. P. M. Johnston for interesting correspondence; and to the Vicar and Mrs. Groves for kindly hospitahty.