A Note on the Mead Way The Street and Doddinghyrnan in Rochester

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

A First Century Urn-Field at Cheriton, near Folkestone

The Roman Watling Street from Canterbury to Dover

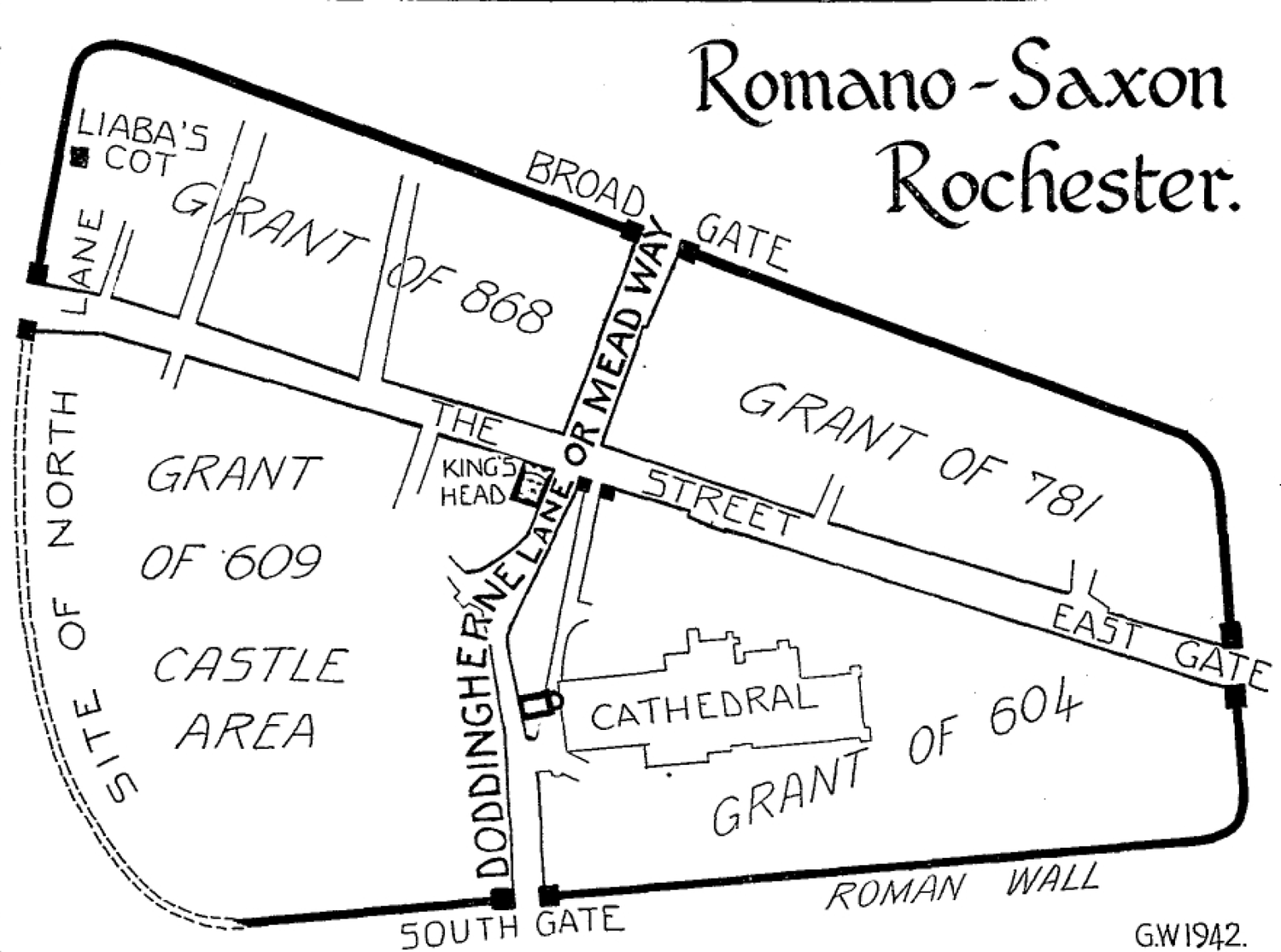

A NOTE ON THE MEAD WAY, THE STREET AND DODDINGHYRNAN IN ROCHESTER By GORDON WARD, M.D., F.S.A. I F you should go to Rochester to-day you will find httle or no knowledge of these names except perhaps that the main road through the City may be known as WatUng Street to the erudite, a name to which it has httle or no right. Nevertheless, in Saxon times, these were street names in common use and the charters give us sufficient information to enable us to identify them to-day. This information takes the form of the recital of boundaries in certain Saxon Charters. The whole of the land within the ancient walls was given to the Church of Rochester by four separate gifts, each giving approximately a quarter of the area. With these gifts there also passed into the hands of the church certain territories beyond the city some at least of which are easily identified to-day. Before discussing the Saxon topography of Rochester it will be well to quote, in translation, the relevant sections of the charters concerned. 1. The first is dated in the year 604 (Text. Roff. cap. 92). It is true that this is often dated in the year 600 but for reasons too long to discuss here the date 604 is to be preferred. These are the boundaries given for the quarter of the city in which the Cathedral stands : Latin. " Omnem terram quae est a medu waie usque ad orientalem portum eivitatis in austrah parte." Translation. All the land which is on the southern side from the Mead Way as far as the east gate of the City. The construction here may seem a httle clumsy but this is the foundation charter of the Priory and there can be no doubt that the church was actually built upon this land south of the main road which had been provided for the purpose. 2. The second charter is of the year 609 (B.C.S. 3) and it hands over what we may call the castle area of the city, in the following words: Anglo-Saxon. " Fram suth geate west andlanges weaUes oth north lanan to straete and swa east fram straete oth Doddinghyrnan ongean brad geat." Translation. From the South Gate westward along the waUs to the north lane, to the street, and so eastward from the street as far as Doddinghyrnan over against the broad gate. 37 THE MEAD WAY, THE STREET AND DODDINGHYRNAN IN ROCHESTER # & %1H5NI^0Q 38 THE MEAD WAY, THE STREET AND DODDINGHYRNAN IN ROCHESTER 3. A charter of about 781 (B.C.S. 242) grants a further quarter of the city adjoining the east gate. This is a corrupt copy of an early charter and it contains many words difficult to interpret. It gives the following boundaries for the lands granted within the city: Mixed Latin and Anglo-Saxon. " Intra menia supradicte civitatis in parte aquilonali, id est, fram Doddinc hyrnan oth tha bradan gatan east be wealle and swa eft suth oth thaet east geat and swa west be strete oth Doddinc hyrnan." Translation. Within the waUs of the said city in the north part, that is, from Doddinghyrnan to the broad gate, east by the wall, and so then south to the east gate, and so west by the street to Doddinghyrnan. 4. The last grant is that of the remaining quarter of the city which was given by a charter of 868 (B.C.S. 518), the boundaries being recited as follows : Anglo-Saxon. " Her sint tha gemaera oth miadowegan, fram Doddinghyrnan west andlanges straete, ut oth weall and swa be northan wege ut oth liabinges cota, and swa be Uabinges cotum oth thaet se weall east sciat, and swa east binnan weaUe oth tha miclan gatan, angean Doddinghirnan, and swa thanne suthan geriaht fram tha gatan andlanges weges, be eastan thi lande, suth oth Doddinghyrnan." Translation. Here are the boundaries as far as the Mead Way : from Doddinghyrnan west along the street out to the wall, and so by the northern way out to Liaba's house, and so by Liaba's house to where the wall turns east, and so east within the wall to the great gate, over against Doddingherne, then straight south from the gate, along the way, to the east of this land, to Doddingherne. THE MEAD WAY The first problem to be faced is that of the Mead Way which seems to have endured as a street name at least from 604 to 868. The name is written " Medu waie " and " Miadowegan." In Anglo-Saxon the word " Medu " or " Miado "—our " meed " and their " mead " (for curiously enough they did not distinguish between the two, a long drink and the due reward of service were synonymous)—undoubtedly meant the Uquid consumed in the beer hall. Our ancestors were heavy drinkers and there are many examples and compounds of this word in the Uterature, e.g. meduaern—a drinldng house, meduburh—a city in which one drinks, medudream—the joy attending mead drinking. These examples are taken from Bosworth and Toller's A-S Dictionary where, in the midst of such words, we find a number of variant spellings 39 THE MEAD WAY, THE STREET AND DODDINGHYRNAN IN ROCHESTER of " Medu-waege " aU of which, however, are translated as referring to the river Medway. Two of them, viz. " partem fluminis Meduwaeian " and " In flumen Medewiaege " undoubtedly do so refer. Nor is it possible from the forms of the name alone to separate those which belong to the river and those which belong to the road in Rochester. We have to accept the fact that the two had somehow got hold of the same name. It seems to belong naturaUy to the road and how it came to be appUed to the river remains a mystery. Where was the Mead way in Rochester ? From the charter of 604 we know only that it abuts upon or joins the main street, quite possibly from the south side, somewhere to the westward of the east gate, but even this is not very clear. In the charter of 868 the boundaries are stated to be given " as far as the Mead way " and the land so bounded is quite clearly the N.W. sector of the city. Its eastern boundary is " andlanges weges "—along the way (this is the genitive following " andlanges," and not the plural), which is presumably a further reference to the Mead way. It is a fair deduction that the Mead Way is the road from the north gate, southward to the centre of the town by College Gate, now caUed Pump Lane but formerly known also as Childergate—the road by the spring. How it came to be caUed the Mead way is difficult to suggest. The following Kentish road names are comparable : A.D. 700. Bereueg—the Barley way. From SeUindge to New Inn Corner. (B.C.S. 98.) A.D. 838. Folcesweg—the people's way, the high way. TheElham valley road at Lyminge. (B.C.S. 419.) A.D. 845. Tafinguueg—% Tafa's way. Somewhere in the Lynsore vaUey, on its east side, probably on the Upper Hardres- Kingston boundary. (B.C.S. 853, a careless copy of a charter in a register.) A.D. 845. Cornuug—the corn way. This should probably have been spelt " Cornuueg." On the west side of the Lynsore valley (B.C.S. 853.) c. A.D. 1070. Welcumeweg—the Ulcombe road, but known only as the name of a church, probably East Sutton. (Arch. Cant., XLV, 60.) A.D. 944. Thone hrycg weg—the ridge way. Somewhere in the Isle of Thanet. (B.C.S. 791.) A.D. 949. Aerne wege—the road fit for running on, a good road. Apparently the Roman road to Reculver where it forms the western boundary of Chislet. (B.C.S. 880, 881.) A.D. 993. Holan wege—the hollow road. A road up the chalk hiUs at the extreme west point of Hastingleigh parish. (Liber de Hyda, p. 244.) 40 THE MEAD WAY, THE STREET AND DODDINGHYRNAN IN ROCHESTER There are also references to the broad highway, etc. This short Ust from Kent charters shows that the Anglo-Saxons allowed themselves a wide range of road names, but neither in this list, nor in the road names which incorporate the words " street " or " path," do we find more than three which may be presumed (on the analogy of the salt ways, e.g. Salthelle, now Oaten Hill, Canterbury, Cant. Cath. Chron., XL, 1944, p. 20, and many others in more northern counties) to be named after the traffic borne on them. In each case this traffic carried one of the essentials of life as understood at the time, com, barley and mead. We may therefore accept the Mead Way without hesitation. Nothing is more Ukely than that mead was brewed on the marshes to the north i of the city of Rochester and brought into the city in barrels, perhaps to the estabUshment of an aheady almost mythical Mr. Dodda, of whom more must be said later. Since Rochester was aheady important enough in 604 to have a bishop we can hardly doubt that the mead business was well established. Nor have we any reason whatever for supposing that Rochester had not been continuously inhabited and provided with hostelries since the Roman occupation. DODDINGHYRNAN We may perhaps pass next to Doddinghyrnan. The word " hyrne " means the same as our word " horn." As a territorial term it means a piece of land projecting into an open space, a lake, etc. In a built up 4 area it would be likely to be a building projecting in some way beyond "• the average building Une. The name Doddinghyrnan means Dodda's Corner building. Dodda is a very well known personal name, in various forms and in various parts of the country. With other names ending in " -a " it comes from the oldest stratum of Anglo-Saxon names. When we speak of Doddinghyrnan we are therefore thinking of some projecting corner building belonging to a man named Dodda. There must have been something about this corner which gave it particularly long celebrity for we meet with " Doddingherne Lane " down to quite recent times. It is now called King's Head Lane. There seems little reason to doubt that Dodda's Corner was actuaUy the site upon which the King's Head now stands for this until recent times projected between the main road and the Epple Market which was situated to the south of it, this market presumably occupying the site of the Roman forum. It is convenient -f to suppose, although evidence is lacking, that Dodda kept a well known hostelry and generally carried on much the same business as the King's Head. It is not really too fanciful to suppose that the mead which was conveyed along the Mead Way was intended for the customers and guests of Dodda. I t may be argued that we have not yet identified Doddinghyrne with 41 THE MEAD WAY, THE STREET AND DODDINGHYRNAN IN ROCHESTER this particular corner. In the 609 charter it is " over against the broad gate " (the North Gate) and is the terminus of a boundary running eastward from the west gate. In the charter of 781 the boundaries run from Doddinghyrnan to the broad gate. This fine must be along the present Pump Lane which is notably short and broad and leads to the North Gate. These facts have aheady been recited in the translations given above but the identification of the position of Doddinghyrnan does not really depend so much on any one of these alone as on the fact that the grants whose boundaries are given can only be made to fit in if Doddinghyrnan be a central point. The accompanying map shows this. If anyone can make any sense of the topography of these four charters on any other plan it will be most interesting to know what he does with Doddinghyrnan. It would be idle to pretend that there have been no other views as to its position. Wallenberg states that the exact position is not known but reproves Karlstrom for identifying it with a place which is probably not in Kent at all (B.C.S. 1101). At least one local archaeologist would place it quite outside the city. St. John Hope in his architectural history of the Cathedral quotes a charter of 1220 in which there is a certain house in Rochester " ad Dodingherne " which is next to the land of the sacristan on the east. He also mentions a charter of 1475 in which " a certain lane called Dodyngesherne Lane " is the western boundary of a property conveyed, but I cannot find that he gives a later date for Doddinghyrne Lane although he evidently knows its position and shows it on a map. The history of Rochester published in 1772 speaks of " Doddingherne or Dodingherne Lane, or, as it implied in English, Dead Man's Lane (a name which is probably obtained from its being a boundary to the cemetery) seems to have lead from the principle street to Boly Hill." The old name was evidently disused at this time. This is the latest memory of the name which I have encountered. It will be noted that few people can have had their name perpetuated so long as Dodda of Doddinghyrne in Rochester. His prominent corner building must have been established at latest in the sixth century and it is not forgotten in the eighteenth or even, if you wiU, in the twentieth. From now on it is assumed that the position of Doddinghyrne is estabUshed on the site of the King's Head and we can pass on to a discussion of the main street. THE STREET This is the only name given to the main road through Rochester in the charters but it is now, sometimes, caUed WatUng Street. To this name it has no right in common usage. The maps of Rochester, at least from 1772, are unanimous in calling it the High Street, nor does the name of WatUng Street appear to occur in the earliest charters 42 THE MEAD WAY, THE STREET AND DODDINGHYRNAN IN ROCHESTER (although no one can pretend to have seen all of them) of post-Conquest date. But as early as about 1135 Henry of Huntingdon took up an old story of Britain having formerly been divided by four great roads, one of which, he said, ran from Dover to Chester and was caUed WatUng Street. There is good reason to suppose that in the neighbourhood of St. Albans this road was called by this name, but the visible extension of the road as far as Dover did not reaUy warrant a similar extension of what was reaUy a local name. Nor was the name one which belonged only to one street but was in use in various parts of the country, and was even applied to the Milky Way. Nevertheless the evil communications of historians corrupted the good manners of the men of Kent, and Somner (1640) speaks of the Dover road in Canterbury as " caUed to this day WatUng Street " and shows it so named on his map. Much more might be said on this subject but it is sufficient to note that the name WatUng Street is, in Kent, a historian's conceit of post-Conquest date and should not be expected to appear in the Saxon charters. In much the same way was the name of the Pilgrim's Way forced on to our maps at a much later date, although the road itself was indeed much more ancient. Why then was the High Street of Rochester called " the Street " instead of by some good Saxon term such as the " here wege "—our " highway " ? There can surely be no other answer than that this is the Latin " stratum " = a pavement, shghtly modified by Celtic or Saxon tongues and so passed on into the onward flowing stream of our language, wherein, after a while, its original > meaning being forgotten, it became applied to roads many of which were innocent of any trace of paving. THE ROMANO-SAXON MAP Rochester was almost the smallest of our known Roman cities, but there is no doubt that it was divided up according to the usual Roman pattern. Very much of this pattern remains to-day. We have first of all the Street, or WatUng Street, which seems to occupy very much its old position although, of course at a much higher level now. The Street runs from the East to the West or river gate, and it had better be noted here that when the Saxons spoke of the East Gate, and when we do so to-day, we really mean a gate which is much more south than east. However, it is inevitable that the Saxon notation should be > continued here. From the north gate to the centre of the town we have a wide road, sometimes called the Broad Gate (for " gate " means a road as well as an opening), and sometimes described as leading to the North or Wide Gate. It has also been named Childergate and is now Pump Lane. There was once a stream of water which ran northwards down this road. This section of road has aheady been discussed 43 THE MEAD WAY, THE STREET AND DODDINGHYRNAN IN ROCHESTER under its oldest name of Mead Way, but it is likely that this name also extended south of the Street. It is this road to the south gate which is most interesting. It was long known as Doddingherne Lane but it is evident that its bent course is hardly what one would expect in a Roman city, for, whatever latitude was permitted elsewhere, the two main roads were usuaUy straight. This westward bend round the Green, the old cemetery, was clearly in existence as early as A.D. 604, as the position of the earhest Saxon Church—indicated on the map—clearly shows. We may call this bend a relic of the Dark Ages. A plausible explanation of its existence would be that some large building, standing somewhere about the site of St. Nicholas church, had coUapsed, and no one had troubled to clear away the debris across the road. It was easier to go round, but the fact that they could go round suggests that there was an open space to the west of the debris. We know that there was such an open space in medieval times and that it was a market place. It is thus not unreasonable to deduce that this was also the Roman market place— occupying as it does a normal position for a Roman plan. It is arguable that this market place was also a relic of the Dark Ages. Attention should further be called to Bull Lane (with its southern extension in the Bull yard), George Lane, and various other roads, or parts of roads, which fit in very well with the normal Roman rectangular road pattern. Thus, although the Castle and the Cathedral areas have between them transformed more than half of the city's 23 acres, there is still left a very significant part of the Roman plan. There is only one means by which such plans can be kept in existence, that is, by their continual use. So soon as an area is devastated, or its fences broken down, cross ways, the shortest ways, come into existence and presently these are the new high ways and the old are built over. That did not happen at Rochester and we may fairly claim that all the evidence we can bring into the picture, although not finally conclusive, should tell us that Rochester at least was continuously occupied throughout the Dark Ages until to-day. That is an archseological fact (i.e. the balance of probabihty as at present envisaged) of no small importance in the history of Kent. 44