The Wotton Survey

Introduction

Jacqueline Bower

I The Manuscript and Methodology

This project was initiated in March 2009. Its primary objective was to transcribe the Wotton Survey1 and publish it online in order to make it available to researchers. A secondary objective was to enable those participating in the project to acquire, or improve, palaeography skills.

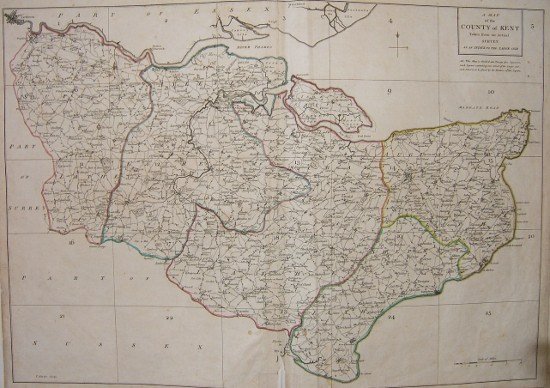

The Wotton family of Boughton Malherbe owned substantial lands in Kent in the sixteenth century. At the time of the Survey their estates totalled about six thousand acres, scattered over every part of the county.2 The Survey was carried out between 1557 and 1560 on the initiative of Thomas Wotton. Its purpose was to establish precisely what lands he held, where they were, how they were used, what feudal obligations they carried and, especially, whether they were ‘of the custom, nature and tenure of gavelkind.’ This was the particular inheritance custom of Kent whereby lands were partitioned equally between all heirs instead of descending in their entirety to the eldest son.3

The Survey was still in the possession of the Wotton family, and still in use, in the early seventeenth century, after Edward Wotton had been ennobled; there is a note about the proceeds of a sale that had come ‘to your lordship‘s use.' 4 Its subsequent history is uncertain. The Wotton male line ended with the death of Thomas Wotton’s grandson, also Thomas, who died in 1630. Over the next three centuries, the Wotton estates, and the papers relating to them, were dispersed to a variety of owners through inheritance or sale.

Thomas Wotton the younger left four daughters. By the marriage of the eldest, Catherine, to Henry Stanhope, Boughton Malherbe and other Wotton lands passed to the Stanhopes, Earls of Chesterfield. Thomas Wotton’s library, and many documents relating to the former Wotton lands also passed to the Stanhopes.

In 1750, much of the former Wotton estate was sold by the Stanhopes to Galfridus Mann, and thenceforward descended through the Mann and Cornwallis families. Some records relating to the estate were also transferred to the Manns.5 Others were retained by the Stanhopes, and were sold, with Thomas Wotton’s library, by the Earl of Caernarvon in 1919. It is unknown whether the Survey was part of this sale. Other documents relating to the Wotton estates, chiefly manorial surveys and rent rolls, were in the hands of private collectors in the 1920s. Some were acquired by the Kent Archaeological Society and are now deposited with their collections at the Centre for Kentish Studies in Maidstone.6

In 1955 the Mann-Cornwallis collection was deposited with the Kent Archives service in Maidstone, where it remains. If the Survey had been in the possession of the Mann-Cornwallis family, it seems likely that it would have been deposited with the rest of the papers.

The Survey, however, is not part of either the Mann-Cornwallis collection or that of the Kent Archaeological Society. If it ever was in the possession of the Mann family, it must have been disposed of separately at some date between 1750, when the Wotton estates were acquired by Galfridus Mann, and 1955, when the papers were deposited with the Kent Archives. Possibly, however, the Manns had never had the Survey.

According to a note in the volume, the Survey was at one time 'in the handes of Thomas Lambard of Sevenoke in Kent'.7 This could have been either Thomas Lambarde who died in 1745, great-great-grandson of the historian and antiquarian William Lambarde, or Thomas Lambarde’s son and heir, another Thomas, who died in 1769. Possibly the Survey passed into the possession of the Lambarde family at the time the former Wotton lands were sold to Galfridus Mann in 1750.

Nothing more is definitely known of the Survey until 1929, when the volume was sold by the auctioneers Hodgson & Co. of Chancery Lane. The identity of the vendor is unknown. It was then, or very soon after, that it was acquired by the British Library. It is described as a ‘recent acquisition’ in the British Museum Quarterly of 1932.8

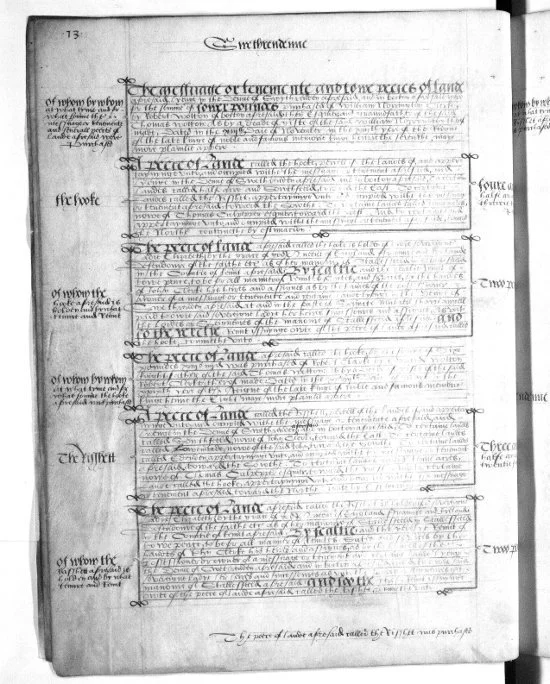

The Survey, with associated documents, is bound in a volume of 365mm by 285mm. It is written on vellum in a good sixteenth century hand. The ink is brown, with rulings and decorations in red. In all there are 338 folios, or 676 pages. The pages were numbered at the time the survey was written up. Folio numbers have been added at a later date. In the transcript, we have used the original page numbers.

The survey is bound in gatherings of two leaves - that is, the scribe has used sheets of vellum folded once to make two folios, or four pages. Where he has started a new sheet, but not needed to use all of it, there are blank pages. For example, the survey of Newestedde in Staplehurst is on pages 416, 417 and 418. Page 419 is blank. The survey of Whiteherste in Marden covers thirteen pages, 397-409. The following three pages are blank.

Sixty seven discrete units of land are described in the Survey. Each section is headed with the name of the land being described. Sometimes it is an entire manor, sometimes a farm or tenement, sometimes what appears to be an assortment of fields, pasture and woodland. Each section begins with a preamble identifying the land and stating when and by whom it was surveyed.

Each field or piece of pasture or woodland is described in a separate paragraph. The name of the piece of land is given in the left hand margin. The main body of the text describes the land, its bounds and usage, and the name of the occupier or ‘fermour’. The acreage or the yearly rent due from the land is given in the right margin.

Each section concludes with an account of how the land came into the possession of the Wottons, by what feudal tenure it was held and what rents or customary services were due from it, and finally whether the land was subject to gavelkind.

In order to carry out the transcription, a group of volunteers was recruited in May 2009. Some were experienced in reading sixteenth century handwriting. Others were complete beginners. Digital images were supplied on CD by the British Library. The volunteers worked from A3 sized paper copies of the digital images. These black and white copies were slightly larger than, and more legible than, the brown ink on cream vellum of the original.

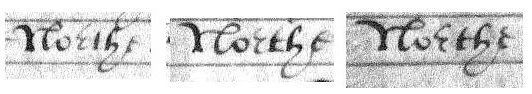

The volunteers worked with speed and efficiency and transcribing was completed in March 2010. Every page was then checked at least once by someone other than the person who transcribed it. We have done our best to remove all mistakes and typos, but it is not possible to be certain that the transcript is one hundred per cent error free, or that all members of the group have interpreted sometimes unfamiliar terminology in the same way. The scribe himself was not always consistent in his capitalisation of place names and personal names, or in the way he formed his capital letters. He had three ways of writing the letter ‘d’, for example.

© The British Library Board. Shelfmark: Add 42715

He had three ways of writing the letter ’l.’

© The British Library Board. Shelfmark: Add 42715

In describing the bounds of the various pieces of land, the scribe frequently named the points of the compass. He was clear and consistent in his capitalisation of North,

© The British Library Board. Shelfmark: Add 42715

South,

and East

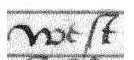

However, it is not so clear that west is always intended to be capitalised.

© The British Library Board. Shelfmark: Add 42715

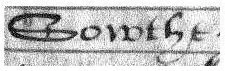

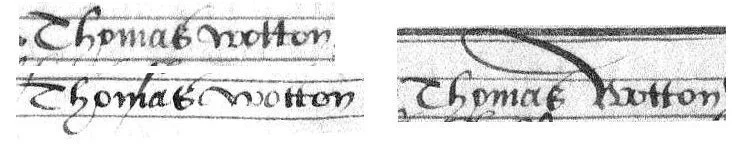

The scribe wrote the name Wotton many times, using several different styles for the initial W.

© The British Library Board. Shelfmark: Add 42715

© The British Library Board. Shelfmark: Add 42715

We decided how to transcribe these on a case by case basis.

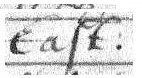

To assist transcribers and checkers, the end of each line in the document was marked in the transcribed text by a slash mark / and a line break. These have been retained in the published version. The scribe did not use many abbreviations. Where they occur, they have been extended by the transcibers, with the letters added between square brackets: cont[eynethe]. Words inserted into the text by the scribe himself are indicated with chevrons: ‘the manoure <of Burscombe> aforesaid’.

Because the Survey is bound in a volume, some of the marginal notes could not be captured in the digital imaging process, and the first few letters of some lines in the main body of the text were also lost. It was found possible to recover most of the marginal notes from the volume in the British Library. They were added to the transcript prior to publication.

Spelling of place names and personal names is inconsistent. A piece of land in the manor of Bocton is spelled Cheryels, Cheriels, Cherils and Cherilles on the same page. A piece of land in Eynsford is variously spelled Tittlea or Tyttlea. An occupier of land in or adjoining the manor of Colbredge was Christofer Edynden, Idenden or Idendenne.9 Boughton (Malherbe), however, is always spelled ’Bocton’. We have not attempted to standardise or modernise spellings in the transcript. However, in this introduction, a single spelling will be adopted for the name of each place or individual referred to. For parish names, the modern spellings will be used.

While the Survey itself is in English, the volume contains several associated documents in Latin. These mostly relate to the Wottons’ title to their estates and to services and obligations issuing out of them. They include the Inquisition Post Mortem on the lands of Nicholas Wotton, great grandfather of Thomas. There is also a lengthy enquiry into the liability of the manor of Bocton for payment towards the maintenance of Dover Castle. These Latin documents have been transcribed but not translated.

The volume also contains a copy of the Act of Parliament of 1548-49 by which the lands which then formed the Wotton estate were disgavelled.

The Survey is a valuable resource for the study of landscape, land usage, tenure and feudal obligations in Kent. It is hoped that this transcript will be of use to scholars and local historians and enable research that will increase our knowledge of the county in the sixteenth century. We would be glad to hear of any research or publication based on the Survey.

Notes

Where books or articles are available online, a link to the website is given at the first reference. However, a subscription or password may be required to access some material.

1. British Library (henceforward BL) Add. Ms. 42,715, henceforward Survey.

2 Michael Zell, ’Landholding and the land Market’, Early Modern Kent 1540-1640 (2000), p.65. The Wotton family and its place in Kent is discussed in Part II of this introduction.

3. Gavelkind, its significance to the Wotton estates, and Thomas Wotton’s reasons for carrying out the Survey, are discussed at greater length in Part III.

4. Survey, p. 444.

5. Centre for Kentish Studies (CKS) U24 Mann Cornwallis papers.

6. BL Catalogue description of Add. Ms. 42,715; http://www.south-derbys.gov.uk/Images/BretbyA4complete_tcm21-85585.pdf ; http://www.kentarchaeology.ac/bcontents.html

7. BL Add. Ms. 42,715.

8. BL Add. Ms. 42,715 i, ii; Robin Flower, ‘A Survey of the Wotton Estate’ The British Museum Quarterly, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1932), pp. 20-21 http://www.jstor.org/stable/i404705

9. Survey, pp. 65, 361, 30, 31.

The Wotton Family

‘The Wottons being a family that hath brought forth divers persons eminent for wisdom and valour, whose heroic acts and noble employments, both in England and in foreign parts, have adorned themselves and this nation, which they have served abroad faithfully in the discharge of their great trust, and prudently in their negociations with several princes; and also served at home with much honour and justice, in their wise managing a great part of the public affairs thereof in the various times both of war and peace.’1

Or, less floridly, the Wotton family, ‘for their learning, fortune, and honors, at times when honors were really such, may truly be said to have been ornaments to their country in general, and to this county in particular.’2

Like many noble and gentry families, the Wottons initially established themselves through trade. The earliest member of the Wotton family so far identified is William, a merchant of the City of London, whose will was proved in August 1391. He owned property in ‘Thamysestret and Wolsyeslane in the parishes of All Hallows the Great and All Hallows upon the Solar… in the lane and parish of S. Laurence aforesaid, and elsewhere.’ His widow Margaret, in her will of 1404, referred to ‘a tenement called "le Cok on the hoop," with wharf, &c., in Thamisestrete in the parish of S. Magnus the Martyr near London Bridge.’ William, and presumably his wife also, was buried in the church of St Lawrence Pountney in the City. This church was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, so if there was any memorial to them there it is now lost.3

After various bequests, both William and Margaret left the residue of their estates to their son Nicholas, a draper. Nicholas was sheriff of London in 1406-07, the year of Richard Whittington’s second mayoralty, and Lord Mayor twice, in 1415-16 and 1430-31.4

A William Wottone was elected alderman for Dowgate in 1388 and was among those representing the City in its dispute with Richard II in the 1390s. A Thomas Wotton, also a draper, was active in the City either side of 1400. Peter Wotton, draper, was a member of the Common Council, representing Bassishaw, in the ninth year of Richard II (1385-86).5 Since it was usual for family members to follow each other in the same trade, it is likely that Peter and Thomas at least were relatives of Nicholas. Research into the records of the Drapers’ Company and of the Corporation of London might reveal more information about Nicholas and other Wottons in the City of London, and about what role, if any, Nicholas played in relations between the City and the Crown at this critical point in English history.

It was common for successful citizens to acquire country estates. Brandon suggests the custom of gavelkind, and consequent active land market, made Kent particularly attractive. John Pulteney, four times Lord Mayor of London, bought the manor of Penshurst in the early fourteenth century. John Peche, clothier and alderman, bought Lullingstone in 1360. Government officials also moved out into Kent. Robert Belknap, Chief Justice (and an ancestor of Edward and Thomas Wotton), acquired Shawstead manor in Chatham and Gillingham and Sandling (Seynctling) in the Cray Valley in the second half of the fourteenth century. Geoffrey Chaucer, Comptroller of the Customs for the Port of London, had an estate in North West Kent.6

The Wotton family tree.

(Opens in resizable new window)

The first generations of the Wotton family to settle in Kent acquired their lands through marriage and inheritance rather than purchase. Nicholas married Joane, daughter and heiress of Robert Corby. The Corby or Corbie family had been established at Eltham and at Widehurst in Marden since the early thirteenth century, if not earlier. The family rose to prominence in the reign of Edward III and was ‘of no small account in this county.’ Robert Corby was sheriff of Kent in the 8th year of Richard II (1384-85).

Through this marriage Nicholas Wotton acquired the manor of Boughton, or Bocton, Malherbe, and Boughton Malherbe was henceforward the principal residence of the Wotton family in Kent. The manor had descended through the female line over several generations prior to Nicholas Wotton acquiring it. It had come to Robert Corby through his wife, Alice, daughter of Sir John Gousall. Sir John Gousall had acquired it from his wife Martha, daughter of Thomas de Dene. The manor had come to the de Dene family through the marriage of Thomas’s father William to Elizabeth de Gatton.7

Descent of the Manor of Boughton Malherbe through the female line.

(Opens in resizable new window)

In addition to Boughton Malherbe, the Corby marriage brought Nicholas Wotton substantial estates in Kent and elsewhere. Joane Corby’s inheritance included Wormshill, Chilton in Sittingbourne, Sheriff’s Court in Minster in Thanet, Thurnham, Whitehurst in Marden and Mardol in Boughton Aluph. Outside Kent, Nicholas Wotton acquired from Robert Corby the manor of Bayhouse at Purfleet in Essex, although it is unclear whether this was through his marriage, or by purchase.8

Joane predeceased Nicholas, and he remarried at least once. He died in 1447/8 leaving a widow, Margaret, and two sons, Nicholas and Richard, a clerk. Nicholas senior bequeathed one third part of his estate, including the manor of Chilton, to Richard, but as a clerk in holy orders, he could have no issue, so his inheritance reverted back to his brother.9

Nicholas Wotton junior married Elizabeth, daughter of John Bamburgh or Bamberg. The marriage brought the manor of Paddlesworth to the Wottons. Nothing is known of John Bamburgh’s life or career; there is no evidence of him having held public office or leaving a will. He was an executor of, and witness to, the will of Nicholas Wotton senior, so was evidently still alive when the will was made in 1447.

Nicholas junior died in 1480 and his widow Elizabeth in 1494. Their memorial brass in Boughton church shows them with three sons and seven daughters, but only one son, Robert, and three daughters appear to have survived to adulthood. The daughters married into the Baker, Cheyney and Cumberland families.10

Nicholas & Elizabeth Wotton brass, Boughton Malberbe church

Nicholas and Elizabeth seem to have had a comfortable but not overly lavish lifestyle. Among the items Elizabeth bequeathed to her daughters were a featherbed with coverings and hangings, sheets of hemp and flax, tablecloths, napkins and towels, several items of brass, a psalter and primer, ‘my best gowne Furred with mynke, a blewe gowne Furred with Black my Furred cloake … my blak gown lined with velvet.’11 On her memorial brass, Elizabeth is shown wearing a gown that appears to be trimmed with fur, possibly mink, at the cuffs and neckline - possibly the gown referred to in the will.

Detail of brass showing trim on Elizabeth’s gown.

Nicholas Wotton junior does not appear to have held any public office. He lived much of his adult life against the background of the Wars of the Roses and the reign of Edward IV; perhaps he was not a supporter of the Yorkists.

The Wottons might have been out of favour under the Yorkists, but they appear to have flourished under the early Tudors. The family seems to have moved up the social scale during the lifetime of Nicholas junior‘s son Robert. Robert Wotton is the first of the family who can be shown to have played a part in public life in Kent. He was sheriff of Kent in the 14th year of Henry VII (1498-99), and was knighted at some point.

Robert also held office further afield. Under Henry VIII he was chief gatekeeper of Calais, lieutenant of Guisnes, and later Comptroller of Calais.12 Calais and the ‘English Pale’ around it were the last remaining English territory in France. Given Henry VIII‘s uncertain relations with France, these were politically and militarily sensitive appointments.

According to Peter Clark, 'The personnel of the Calais garrison and administration was increasingly recruited from Kentish folk; landholding on both sides of the Channel was fairly common and in time of war Calais was largely provisioned from the county.’ Kent and Calais may have together formed a regional economy that counterbalanced the increasing pull of London in this period. The need to provision Calais, Guisnes and English Pale stimulated the economies of Kent and East Sussex, it is suggested. This need may have been a factor in the apparent preference for gentlemen from Kent as officeholders in Calais. As landowners, gentlemen such as Robert Wotton would have had access to the quantities of supplies needed, and been aware, through their stewards, of local market conditions.13

Robert Wotton married Anne Belknap, daughter of Sir Henry Belknap, who held lands in Warwickshire, Essex, Sussex and Kent. He died in 1488. ‘Robard Wotton’ was one of his executors. Sir Henry’s heir, Edward Belknap, also held office in Calais; he was one of the Commissioners responsible for overseeing the construction of the encampment at the ‘Field of the Cloth of Gold’ for Henry VIII’s meeting with Francis I of France in June 1520. The king’s retinue of six thousand men and women was bigger than the population of most, if not all, towns in Kent at the time. The ‘temporary’ palace was built of stone, brick, wood and canvas. Three of the rooms were larger than any room in any of the king’s palaces in England.1

Edward Belknap died in 1521. His estates were divided between his sisters Elizabeth Cooke, Mary Danett and Anne Wotton. The Wottons thereby acquired a one third share of the manors of Ringwould, Saintling Okemere in St Mary Cray and Old Longport in Lydd, as well as land in Warwickshire.15

The Wottons and the Belknaps.

(Opens in resizable new window)

In May 1522 Robert Wotton was ‘sore vexed with contynewall infyrmite and by all symylitude of no longe perseverance in this liff.' In July he was still `very seke'. He died in 1524. In his will he asked, if he died in Calais, to be buried next to his late wife Anne, before the altar of the church of the Blessed Mary the Virgin of the Order of Carmelite Friars in Calais. This church was suppressed by Henry VIII, so no memorial to Anne or Robert Wotton survives.16

Robert Wotton appears to have had a more lavish lifestyle than his parents, possibly due to the requirements of his office. His will mentions gold crosses and chains, silver plate, and cloth of silver bought to make him a coat. The spiritual bequests in the will indicate an orthodox Catholicism; he required his son Edward and Edward’s heirs to provide, out of their inheritance, a priest to sing in the church at Boughton Malherbe for twenty years for the souls of his ‘fader and moder’, for the souls of Robert himself and Anne, and for all Christian souls. The will shows that the family’s Continental links stretched beyond Calais; Robert’s nephew William Baker was a student at Louvain, one of the leading universities of the sixteenth century.17

Six of Robert and Anne’s nine children survived to adulthood. Their daughter Idonea married Thomas Norton ‘of Calais’. Mary married first into the Guldeford family of Leeds in Kent, then into the Carew family of Devon. Margaret married first William Medley, then Thomas Grey, second Marquess of Dorset, grandson of Elizabeth Woodville and thus a cousin of the King. This marriage elevated the family, or at least Margaret, from the gentry to the aristocracy and brought them close to the Court and the political intrigues of the mid sixteenth century; Margaret and Thomas’s son Henry was the father of Lady Jane Grey.18

Robert Wotton’s heir was his son Edward. His second surviving son, Anthony, was a monk at Canterbury. The third, Nicholas, born about 1497, was also a churchman and diplomat. Edward and Nicholas did not conform to their father’s conservative religious beliefs. Clark suggests that Edward was one of a number of Kent gentlemen holding radical religious views in the 1530s. Nicholas was one of a humanist circle that flourished at Canterbury in the later 1520s.19

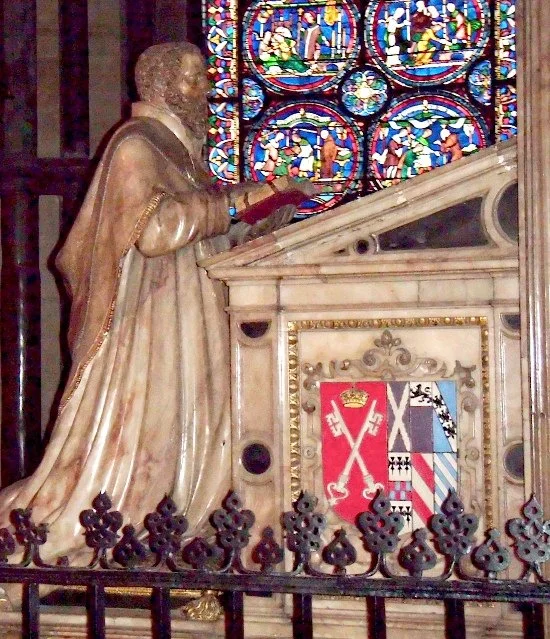

Although an ordained priest and Dean of Canterbury and of York, Nicholas Wotton followed a career in law and diplomacy. He held office under Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth, serving as ambassador to Cleves, the Netherlands, the Empire, France and Germany. He is described as ‘one of the most long-serving, and probably the last, of the great early Tudor clerical diplomats‘. Nicholas Wotton died in 1567 and was buried in Canterbury Cathedral. 20

© 2012 Graham Stark

Nicholas Wotton - memorial at Canterbury Cathedral.

Edward Wotton was born about 1489. He was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in 1511. It was becoming common for the sons of gentlemen to spend time at the inns of court instead of, or in addition to, university. As well as the useful social connections to be made, knowledge of the law was valuable to men who might have to deal with complicated legal matters in connection with their own estates, and who were likely also to be required to serve as magistrates. Possibly through the influence of his father in law, Edward Wotton was a ‘filazer’ - a court official - at Westminster from 1513.21

The next phase of Edward Wotton’s career was typical of many county gentlemen. He was a Justice of the Peace in 1524, knighted by 1528 and sheriff in 1529 and 1535. He was present at a number of court occasions, including the coronation of Anne Boleyn in 1533 and the baptism of Prince Edward (the future Edward VI) in 1537, and was among those who travelled to Calais to greet Anne of Cleves on her way to England in 1539. The following year he was appointed treasurer of Calais. Much of his work there involved overseeing the extensive refortification of the town, and preparation for war with France. He continued his career in public service into the reign of Edward VI.22

Edward also paid attention to the family estates. During the 1520s he substantially extended Boughton Place, the Wottons’ principal seat at Boughton Malherbe. He added to his estates by marriage and by purchase, taking advantage of the active land market in Kent when monastic estates became available following the Dissolutions. In 1539 and 1549 he was one of a number of Kent gentlemen who sought Acts of Parliament to disgavel their estates. These disgavelling Acts led to the Survey which was carried out by Edward Wotton’s son Thomas and is transcribed here. The disgavelling Acts are discussed at greater length in Part III of this introduction.23

West wing of Boughton Place viewed from the Greensand Way.

Edward Wotton was married twice. His first wife, Dorothy or Dorothea Rede or Reed, was the daughter of Sir Robert Rede, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas. She was the mother of Edward’s heir, Thomas. Like Robert Wotton’s brother in law Edward Belknap, and Idonea Wotton’s husband Thomas Norton, the Redes had links with Calais. Robert Rede’s father, Dorothy’s grandfather, was a Lincolnshire man who traded as a Calais merchant. Further research into the English community at Calais might reveal more about their family connections and business interests there.

Robert Rede’s wife was Margaret, daughter of John Alfegh or Alphay of Chiddingstone. Through this marriage Robert Rede acquired land in Kent which eventually passed to Edward Wotton by his marriage to Dorothy. The Rede lands included manors in Eynsford and Cliffe and other lands in Sittingbourne, Brenchley and Hadlow.24

Dorothy died in 1529. Edward married secondly Ursula, daughter of Sir Robert Dymoke of Scrivelsby, Lincolnshire, and widow of Sir John Rudston, draper and former Lord Mayor of London.25

Edward Wotton died in 1551. In his will he asked to be buried in the choir of Boughton Malherbe parish church. There is a memorial brass to him there.

Edward Wotton memorial brass in Boughton Malherbe church

Edward Wotton’s will indicates an austere personality with strongly Protestant beliefs. He refers to his ‘bodie or vile Carkas’ and to his soul being received by God ‘into the number of his Elect.’

‘Where oftentimes greate summes of money be wastfully spent and consumede aswell in Bowelynge and Ceryng of the corps, as also in the funerall (to wyt in blacke clothe for Morners and servantes) in a hersse with lights and deckyde with schochyns of Armes, with cote Armes, helmet and sworde with suche other ceremonyes usually don by the heraulds at Armes with suche lyke, I do utterly charge myne Executours that in nowyse they bestowe one peny in eny of all the foresaide thinges.’26

There was a somewhat pointed legacy for the King:

‘Where the King of most famous memorye King Henry theight my late Master by his testament dyd give and bequeathe to me three hundreth poundes, whiche I have not yet recevyde, I do frely Remytt and give to the King’s Maiestie our present Master the said legacie and some of three hundreth poundes.’

Edward Wotton was survived by his sons Thomas and William and daughter Anne. Two more sons and a daughter died young. Family relationships became complicated in this generation. Brother and sister Thomas and Ann Wotton married sister and brother Elizabeth and Robert Rudstone, daughter and son of their stepmother Ursula by her first marriage to Sir John Rudstone. William Wotton married Mary Danett, descendant of one of the co-heirs of the Belknap estates.27

Thomas, born in or before 1521, was his father’s principal heir. While his father Edward’s and uncle Nicholas’s lives are reasonably well documented, Thomas’s is not. He appears in the Dictionary of National Biography only as an addendum to his father’s life.

Thomas was educated at Lincoln’s Inn and at Cambridge. He probably spent time in Calais when his father was there and is also believed to have visited Paris as a young man.28

Having succeeded his father at Boughton Malherbe, Thomas Wotton might also have expected to follow him in a career in government service, perhaps holding an appointment at Calais as both his father and grandfather had done. However, while his father and grandfather had successfully negotiated the uncertainties of Tudor politics in the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, Thomas found himself vulnerable under Mary.

On the death of Edward VI in July 1553, the Duke of Northumberland proclaimed his daughter in law Lady Jane Grey queen.29 The attempted coup collapsed after nine days and Mary Tudor succeeded to the throne. Northumberland was executed. Jane and her husband, Northumberland’s son Guildford Dudley, were imprisoned in the Tower. Lady Jane’s father, Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, Thomas Wotton’s first cousin, remained free.

The Wottons and Greys.

(Opens in resizable new window)

There is no evidence that Thomas Wotton was in any way implicated in Northumberland’s attempted usurpation. A few months later, however, events in Kent placed him much closer to potential treason.

Mary Tudor’s intention of marrying Philip II of Spain aroused the opposition of many of her subjects. Kent had already experienced economically motivated disturbances in 1551 and 1552. Late in 1553 Thomas Wyatt of Allington, a close contemporary of Thomas Wotton, began to conspire with other gentlemen in Kent to lead an uprising against the Spanish marriage. There were to be simultaneous risings in Herefordshire, in Devon and in East Anglia, the East Anglian rising to be led by Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk. Although the stated aim of the rebels was only to stop the Spanish marriage, it was widely suspected that at least some of them intended to depose Mary and place Elizabeth on the throne instead. Additionally, Wyatt and other conspirators, like the Wottons, owned former monastic lands. It was known that Mary wished to restore those lands to the church. Preserving their estates therefore provided additional motivation for the plotters.

Wyatt’s co-conspirators in Kent were thirty or so gentry from the Medway Valley area, many of whom were linked by marriage. The plot was also known and supported by the French ambassador; France had an interest in stopping the Spanish marriage.

In January 1554 Wyatt led his followers out of Kent. They reached Westminster and attempted to enter the City. The situation might have become critical, but after initial uncertainty and weak leadership among the queen’s advisors, the rebellion crumbled. Wyatt was arrested and executed, as was Thomas Wotton’s cousin the Duke of Suffolk, and also Lady Jane Grey and Guildford Dudley, although they had not been in any way involved the rebellion. Elizabeth was suspected of having supported the rebels and for a time she too was in danger, but nothing could be proved. She spent two months in the Tower but her life was spared. 30

In such a closely connected community as the Kent gentry, it seems unlikely that Thomas Wotton knew nothing of the conspiracy, even if he was not directly involved. If he had intended to take part in the rebellion, however, he was prevented from doing so. The rising in Kent began on 25 January 1554. Four days before that, Thomas was committed to the Fleet ‘to remain a close prisoner … for obstinate standing against matters of religion.’ 31

The exact circumstances of Thomas’s arrest and imprisonment are unknown. According to Isaak Walton,

‘Nicholas Wotton, Dean of Canterbury, being then Ambassador in France, dreamed that his nephew, this Thomas Wotton, was inclined to be a party in such a project, as, if he were not suddenly prevented, would turn both to the loss of his life, and ruin of his family….

‘Considering also that Almighty God (though the causes of dreams be often unknown) hath … by a certain illumination of the soul in sleep, discovered many things that human wisdom could not foresee: Upon these considerations he resolved to use so prudent a remedy, by way of prevention, as might introduce no great inconvenience either to himself or to his nephew.

‘And to that end, he wrote to the Queen, and besought her, That she would cause his nephew, Thomas Wotton, to be sent for out of Kent; and that the Lords of her Council might interrogate him in some such feigned questions, as might give a colour for his commitment into a favourable prison; declaring that he would acquaint her Majesty with the true reason of his request, when he should next become so happy as to see and speak to her Majesty….’32

Leaving aside the story of the dream, it is quite plausible that Nicholas Wotton heard of the Wyatt conspiracy, either from acquaintances in Kent or through his diplomatic contacts in France, and determined to keep his nephew out of it by having him arrested on a lesser charge.

The author of a pamphlet on the Wyat rebellion wrote

‘It befell … that … the Privy Council committed a Gentleman of that Shire [Kent] to Ward, one to Wyat above all others most dear: whereby the common bruit grew that he (suspecting his secrets to be revealed, and upon that occasion to be sent for by the Council) felt himself, as it were for his own surety, compelled to anticipate his time. But whether that were the cause or no, doubtful is.’33

It is suggested that the gentleman referred to was Thomas Wotton, and that it was he who revealed Wyat’s plans to the authorities. Even if Thomas did speak of anything he might have known, it is highly unlikely that it would have made any difference to the course of events. His imprisonment occurred only days before the rising; the authorities had known long before that a conspiracy was in progress.

Thomas was still in prison on 4 March. The date of his release is unknown. In a letter to Francis Walsingham written in 1578, Thomas seems to suggest that Walsingham was responsible for securing his release.

‘Thus have you first delyvered mee (without good cause surely as I thincke, once shut up in prisonne,) and nowe for my sake my sonne.’34

However, this must refer to some later, as yet unidentified, imprisonment. Walsingham was abroad throughout Mary’s reign and was in any case too young at the time to have had that much influence over the Privy Council.35

The former Margaret Wotton, Marchioness of Dorset, Henry Grey’s mother and Thomas’s aunt, did not live to see the execution of her son and granddaughter, having died in or soon after 1535.36

The loss of one or more family members to the executioner’s block was not an unusual experience for the gentry and aristocracy in the Tudor period. Thomas’s will and his letters show that he was aware of his wider family connections.37 It is impossible to know how close he was to his Grey cousins, and how deeply he might have been affected by the executions of Henry and Jane, but the events of 1553 and 1554 perhaps explain why he held no public office at national level during Mary’s reign. Although his uncle Nicholas continued to serve the crown as a diplomat (albeit at a safe distance, in Paris, until the outbreak of war with France in 1557), Thomas may have considered it wise to keep a low profile.

He did, however, hold office at local level. He was sheriff of Kent in the fourth and fifth years of Mary’s reign, completing his second shrievalty under Elizabeth. He was sheriff again in 1577-78. In August 1573 the Queen visited Boughton Place on her progress through Kent. Thomas ‘had many invitations from Queen Elizabeth to change his … retirement for a Court, offering him a knighthood … and that to be but as an earnest of some more honourable and profitable employment, yet he humbly refused both’.38

Thomas could not, of course, continue the family tradition of office holding in Calais following its capture by the French in 1558. In 1574 it was rumoured that he was to have an appointment in Ireland, but, he wrote, ‘I am not (I thanke God) so ambitious as that for a little honoure. I sholde take upon me an office of greater weight then my shoulders ar hable to bear, and so eyther fall and shame meself, (which were yll), or by simple service for lacke of good knowledge hynder her Matie and the Realme (which were woorse).’39

Both Nicholas and Thomas served on a Commission established by the Queen in 1561 to investigate the ‘ruyne and decaye’ of Rochester Bridge and take immediate steps for its repair. The main work of reviewing the bridge accounts was undertaken by Nicholas, Richard Sackville and William Lovelace. Thomas served on a second Commission in 1571 (Nicholas had died by this time) and a third in 1573. This Commission led to the Rochester Bridge Act of 1576. The Act required the parishes which contributed to the upkeep of the Bridge to elect annually two wardens, twelve assistants, and four auditors to manage the Bridge estates and accounts and ensure the maintenance of the Bridge. Thomas served as one of the auditors in this new system’s first year of operation. In 1583 he was Senior Warden.40

Rochester Bridge 1795

‘You maye saie, Good madame, that I doo in a presumptuous sorte moche forget mee selfe in the first Letter that ever I sent you, and afore that ever I spake wythe you, in a matter of charge to present a petition unto you.

'The reaporte of your great curtesye and bountie of thone side dothe incourage mee; the necessitie of the thing I have in hande of thother syde dothe constrayne mee unto yt. Yf emong other of yout most vertuous actions, yt might please you to bestowe some good Portion of moneye upon Rochester Brydge, you shall hardelye bestowe yt upon any persounes that wyll more gratefullye receyve yt then th officers of that Brydge, (wherof unworthily I am one), you can hardlye bestowe yt upon any woorke that ys in shewe more bewtifull; in stuffe or matter more notable; in trade rnore usuall; in use more necessarye; and in present estate more ruinous then Rochester Brydge. Yf I had not ihis Sommer of myne awne moneye bestowed upon yt lixiviij li yt had surelye fallen into a verye great decaye.

'You knowe, right vertuous Ladye, that Beggars maye be no choosers; towarde this good purpose appoynt what ye will, and when ye will. I will therof, God willing, towarde a continuall rememberance of your most virtuous disposition among our recordes make a speciall note.'

Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, was only in her early twenties at the time this letter was written. Thomas Wotton was forty years older. The highly respectful tone of the letter might be because Thomas was asking for money from someone he did not know, or may reflect the difference in social status which Thomas may have perceived to exist between them. Mary Herbert's mother, Mary Sidney, born Mary Dudley, was a sister of John, Duke of Northumberland, and Robert, Elizabeth I’s Earl of Leicester.

Thomas was a public spirited man. He wrote many letters seeking the help of prominent men on behalf of acquaintances, or with county business. He wrote to the highest in the land - Leicester, Burghley, Walsingham - but the correspondence is formal and business like; there is no suggestion that he was on intimate terms with any of these men.

In February 1573 he asked Sir Henry Sidney to use his influence with his servant, Thomas Finch, on behalf of Mrs Finch. Mrs Finch, who was evidently living apart from her husband, had appealed to Thomas for help in resolving her marital troubles. In June 1574 Thomas wrote to the Archbishop, Matthew Parker, about ‘poore Bonham, in profession a christian man, in conversation a virtuous man’, who was imprisoned for failing to conform to the Church of England.42

Although Northumberland had fallen in 1553, the Dudleys were still prominent and powerful. Thomas had dealings with members of the family on more than one occasion. In March 1578 he wrote to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, the Queen’s Master of the Horse, appealing for a reduction in the quantity of oats the county was required to supply to the Queen’s stables.43

In September 1582 he rejected an appeal from Ambrose Dudley, Earl of Warwick, brother of Northumberland and Leicester, on behalf of Thomas Wandenne, apparently a servant or protégé of Warwick’s;

‘Our bounden dutyes unto your good Lordeshippe most humblie remembered. Right sorye ar wee that the lewde demeanure of Thomas Wandenne dothe holde us from shewing hym that favoure that for the dutye wee owe unto you, the sight of your lyverye alone might otherwyse easelye bryng us unto. At the last quarter sessions holden in this place, accused to be, and by good testimonye proved to be a person moche bent unto quarreling.

'And here also then accused, and by like testimonye well proved to have uttered verye sclaunderous woordes against Mr Hendeleye (whom all wee and besyde us a great nomber, for his great yeres and vertuous course of lyfe, doo highlye esteeme), hee was by recognisaunce bounde to his good behavoure.

'Sythens which tyme hee ys here also shrewdelye suspected to have corrupted sondrye bagges of woade, the doying wherof dyd tende to the great losse and hynderaunce of dyvers honest Personnes.

'The consideracon of whiche thinges thus layed together hathe inforced us in this Sessions towarde hym to doo as moche as wee dyd in the last Sessions. Wherof (and so of the disposition of the persoun hym self), wee thought meete to advertise your good Lordeshippe. And thus wee beseeche the Lorde in honourable estate to sende you a course of many ioyfull yeres.’44

There is a marked difference in tone between this letter and Thomas’s appeal to Warwick’s niece, the Countess of Pembroke, the following year. Between the minimal courtesies here there is a fairly brisk dismissal of what appears to have been an attempt by Warwick to interfere in county justice.

Thomas’s one known sporting interest was deer hunting. He spent more than £56 enclosing South Park in Boughton Malherbe in 1567, although ‘The days of deer hunting were moving to a close.’ Deer parks were being converted into farmland, as the rising population led to rising demand for agricultural produce and rising prices.45

The park was stocked with ‘six score deer’. These had come ‘from the nomber of 30 deere of all sortes by the gifte and graunte of John Tufton Esquire had owt of the parke of Westwell … in the iiiith of November 1561.’46

Thomas in turn made gifts of deer to others. In 1580, ‘to his verye assured frende Mr Best’, ‘of all the deere that ever you had, I sende you (I feare) the worst, and yet of all those that I nowe have, I sende you (I thincke) the best. But seeing hee ys neyther suche as you deserve, nor suche as for you I desyre hee sholde bee, in the place of this I praye you, appoynt when and where ye will have suche as my Parke can geve, for suche hathe your curtesye ben towarde mee, as at my handes yt deservethe greater matter then Buckes.’47

Antiquarianism and other scholarly interests were common pursuits among gentlemen in Kent. In the seventeenth century Edward Dering acquired a substantial collection of manuscripts dating back to the Anglo Saxon period. In the eighteenth century Edward Hasted published his parish by parish History and Topographical Description of Kent.

Nicholas Wotton compiled a collection of histories and genealogies of distinguished English and French families, derived from books and manuscripts borrowed from friends and acquaintances.48

Thomas probably made some of his uncle’s manuscripts available to William Lambarde, the first historian of Kent, for use in his research. When Lambarde was seeking informed opinions on his Perambulation of Kent, prior to its publication, he sent the manuscript to ‘the Right Woorshipfull, and vertuous, M. Thomas Wotton, Esquier’. In his dedication to Thomas in the published work, Lambarde wrote ‘When I [was] minded to communicate the same with some such of this Countrie, as for skill abundantly could, and for good will indifferently would, weigh and peruse it, You (Right Woorshipfull) came first to my minde, who, for the good understanding and interest that you have in this Shire, can (as well as any other) discerne of this dooing, And to whom (beyond other) I thought my selfe for sundry great courtesies most deepely bound and indebted.’ Thomas, returning the compliment, wrote a preface commending the work to the gentlemen of the county.49

Thomas Wotton’s greatest personal interest seems to have been his library of books with fine bindings. He is believed to have been the first Englishman to assemble a library of gold-tooled bindings, most of which he acquired in Paris around 1550-1552.

His library included works by Chaucer, Cicero and Pliny, a ten volume edition of Ersamus’s works, Bernardo Ochino’s Tragoedie or Dialoge of the unjuste usurped primacie of the Bishop of Rome, (1549) translated by John Ponet, a leading Protestant theologian, Bishop of Rochester under Edward VI.50

The greater part of the library passed through the hands of Thomas’s descendants into the possession of the Stanhopes, Earls of Chesterfield and ultimately to the fifth Earl of Caernarvon. It was sold by him, and the volumes dispersed, in 1919. About 140 books in existence today can be identified as having belonged to Thomas. Some are in the British Library. Some are in the library of Eton College. Others are in the United States. One volume sold by Christie’s in New York in 2005 achieved a price of $31,200.51

Thomas married twice. His first wife, whom he married before 1545, was Elizabeth, daughter of Sir John Rudstone. They had six sons and three daughters. Elizabeth died in 1564. Thomas subsequently married Heleonor, daughter of William Finch of Eastwell, widow of Robert Morton. Thomas and Heleonor had two sons.52 By his marriage to Heleonor, Thomas also became stepfather to her son George Morton. George seems to have been a less than satisfactory stepson. In July 1582 Thomas wrote to him

‘Howe the state of your lyving maye maynteyne the charges that your abode in London dothe put you unto, How your abode there without cause dothe answer the dutie ye owe unto your virtuous wife and Childerne (as farre as I can see left to themselves in the Countreye), every man maye easelye judge.’53

Thomas died in 1587. His will displays the same austere attitude to funerals as his father. He wanted to buried ‘without any manner of pompe … without sermon Armes or Banners black gownes or Coates or the presence of other persons then such as maye be accepted my ordinarye and Daylye familye.’54

There is an alabaster memorial bust to Thomas on the north side of the chancel in Boughton Malherbe church.

Thomas Wotton memorial bust in Boughton Malherbe church

W.E. Moss, a collector and bibliophile who compiled a catalogue of Thomas’s library, believed the bust was ‘a mass produced thing and not portraiture.’55 Nothing that is known of Thomas’s character suggests that he would have been pleased with a mass produced memorial, but if he left no instructions (there are none in his will) then it would have been the choice of his widow and his heir.

In his will Thomas made bequests of varying sums of money to more than twenty named male servants. He also refers to ‘the rest of my yeomen servants as … being my household servants doe take my yearely wages.’ Possibly these were farm servants working on the demesne at Boughton Malherbe. Boughton Place was a substantial house, but it seems improbable that there would have been enough work for this number of male servants plus an unknown number of women servants. (The will mentions Mary Whitton, who was perhaps the housekeeper, plus unspecified women servants.) It sounds more like the retinue of a minor medieval nobleman than the household of an Elizabethan country gentleman. Possibly research into the named servants would shed light on what role they played in Thomas’s household.

Thomas seems to have been respected by all who knew him. Renolde Scot of Smeeth described him as ‘a man of great worship and wisedome, and for deciding and ordering of matters in this commonwealth, of rare and singular dexteritie.’56

Isaak Walton, who knew his son Henry, wrote that Thomas was ‘a gentleman excellently educated and studious in all the liberal arts… a man of great modesty, of a most plain and single heart, of an ancient freedom and integrity of mind… This Thomas was also remarkable for hospitality, a great lover and much beloved of his country; to which may justly be added that he was a cherisher of learning.’57

The editor of his letters described him as ‘a man of strong character, austere, and utterly devoid of humour.’ This assessment is unfair, since the letters on which it was based were mostly formal, addressed to men of superior social status. They were not the place for humour or frivolity.58

Thomas was typical of the Kent gentry of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Extensive family connections, not overly ambitious, conscientious in his attention to his estates and to county affairs, honourable, well respected and scholarly. He seems to have been comfortable with people in all walks of life, from the highest to the lowest. At one time he was entertaining the Queen at Boughton Place. At another he was walking or riding around fields and overgrown woods, observing while his servants measured out his lands. As he himself said, he was ‘brought up … in the Countrye about Countrye causes …. In a meane estate contented wythe that that the Lorde hathe sent me, being many wayes moche more then I have deserved, and every waye as moche as I desyre.’59

There is scope for further research into Thomas Wotton’s life, especially his family connections, his role in county affairs and his religious beliefs.

Descendants of Thomas Wotton.

(Opens in resizable new window)

Four of Thomas’s sons - Edward, James, John and Henry - were knighted. James was a soldier, who took part in a raid on Cadiz. Henry travelled widely in Europe, carried out diplomatic missions for James I, and ultimately became provost of Eton. John died too young to have become established in any career.60

Edward was Thomas’s heir at Boughton Malherbe. He was a courtier and diplomat under Elizabeth and James I. In 1603 James created him Baron Wotton of Marley (one of the Wotton manors, in Harrietsham). He served as MP, JP, sheriff and Lord Lieutenant in Kent.61

Edward married Hester, natural daughter and heiress of William Pickering. Pickering had served in Calais under Henry VIII, so this was possibly an old Wotton family connection. Hester died in 1592. Edward subsequently married Margaret, daughter of Philip, third Baron Wharton.

In the early seventeenth century Edward rejected the Protestantism of his father and grandfather and converted to Catholicism. He avoided notice until 1624, when he was summoned before the Quarter Sessions on charges of recusancy. Because of his age (he was seventy six), his long service to the county and the country, and the respect with which his family was regarded, the magistrates took no action against him.

Edward died in 1628. His heir was his son Thomas, who was also a Catholic. Thomas survived his father by only two years. He had no son; his heirs were his four daughters. The greater part of the Wotton estate, including Boughton Malherbe, passed to the eldest daughter, Catherine. She was married to Philip Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield, and her part of the Wotton estates passed down through the Stanhope family until 1750, when it was sold. 62

This is not intended to have been an exhaustive account of the Wotton family in Kent. Its purpose has been to provide some background and context for the Survey, to draw together in one place all the aspects of Thomas Wotton’s life, which has only been written in a fragmentary fashion, and to suggest further avenues for research into the family.

Where books or articles are available online, a link to the website is given at the first reference. However, a subscription or password may be required to access some material.1. Izaak Walton, Lives of John Donne, Henry Wotton, Richard Hooker, George Herbert, &c. http://www.archive.org

2. Edward Hasted, The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 5 (1798), pp. 397-415. http://www.british-history.ac.uk

3. Wills: 21 Richard II (1397-8); Wills: 6 Henry IV (1404-5); Calendar of wills proved and enrolled in the Court of Husting, London: Part 2: 1358-1688 (1890). http://www.british-history.ac.uk/

4. The Visitation of Kent, Taken in the Years 1574 and 1592 (1924); Hasted, op. cit.

5. Reginald R. Sharpe (editor) Calendar of letter-books of the City of London: H: 1375-1399 (1907), pp. 380-396; Calendar of letter-books of the City of London: K: Henry VI (1911); Calendar of the plea and memoranda rolls of the City of London: volume 3: 1381-1412 (1932), ) http://www.british-history.ac.uk

6. Peter Brandon, The North Downs (2005) p.86.

7. Hasted, op. cit., Vol. 1, Vol. 7, (1798). http://www.british-history.ac.uk

8. A History of the County of Essex: Volume 8 (1983), pp. 57-74. http://www.british-history.ac.uk

9. Visitation, op. cit.; Abstract Will of Nicholas Wotton http://www.kentarchaeology.org.uk/Research/Libr/Wills

10. Visitation, op.cit.

11. Will of Elizabeth Wotton, CKS PRC32/4/27

12. Hasted, op. cit.; Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 2: 1515- 1518 (1864). http://www.british-history.ac.uk

13. Peter Clark, English Provincial Society from the Reformation to the Revolution: Religion, Politics and Society in Kent, 1500-1640, (1977), p.11; Mavis E Mate, Trade and Economic Developments 1450-1550; The Experience of Kent, Surrey, and Sussex, (2006).

14. Victoria County History: Warwickshire http://www.british-history.ac.uk; Will of Henry Belknap TNA PROB 11/8; ed. John Nichols, Chronicle of Calais in the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII to the year 1540, http://www.archive.org. Jasper Ridley, Henry VIII (1985) p.118. A painting of the Field of the Cloth of Gold, by an unknown artist is in the Royal Collection; http://www.royalcollection.org.uk

15. Will of Edward Belknap TNA PROB 11/20.

16. State Papers, quoted in David Potter, ‘Sir John Gage, Tudor Courtier and Soldier (1479-1556)’, English Historical Review, cxvii, November 2002; Will of Robert Wotton TNA PROB11/21; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03354a.htm

17. Will of Robert Wotton TNA PROB11/21. Louvain was in the Duchy of Brabant, present day Belgium, in the sixteenth century part of the dominions of the Hapsburgs.

18. Visitation, op.cit.; Robert C. Braddock, ‘Grey, Thomas, second marquess of Dorset (1477–1530)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004). [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/11561, accessed 1 April 2011]

19. Visitation, op. cit.; Clark, op. cit. pp 52, 29.cit

20. For a full account of Nicholas Wotton’s career see Michael Zell, ‘Nicholas Wotton‘, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004). [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/30002, accessed 5 Dec 2010]

21. Records of the Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn: Admissions 1420-1799. http://www.archive.org ; Clark op. cit. p.18; J. H. Baker, ‘Rede, Sir Robert (d. 1519)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004); [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/23247, accessed 6 Dec 2010]; Oxford English Dictionary.

22. For a full account of Edward Wotton’s career see Luke MacMahon, ‘Edward Wotton‘, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29998, accessed 5 Dec 2010]

23. Anthony Quiney, Kent Houses (1993) p.180; Michael Zell, Early Modern Kent 1540-1640, p.64.

24. Robert Rede, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; Survey.

25. Edward Wotton, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

26. Will of Edward Wotton TNA PROB11/34.

27. Visitation, op.cit.

28. Edward Wotton, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; http://venn.lib.cam.ac.uk/Documents/acad/intro.html

29. Historians debate how far this was Northumberland’s initiative alone, in an attempt to maintain his own position of power after the death of Edward VI, and how far it was the wish of the young king himself, as a means of securing the Protestant succession.

30. Clark, op. cit., p.87.

31. John Roche Dasent (ed.) Acts of the Privy Council of England vol 4 1552-1554 p.389 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/

32. Walton, Lives.

33. John Proctor, 'Wyat’s Rebellion; with the order and manner of resisting the same', (1555) Tudor Tracts, 1532-1588. http://books.google.co.uk/

34. G. Eland (ed.) Thomas Wotton’s Letter-Book 1574-1586 (1960) p.16.

35. Simon Adams, Alan Bryson, and Mitchell Leimon, ‘Walsingham, Sir Francis (c.1532–1590)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004); [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28624, accessed 1 April 2011]

36. Thomas Grey, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

37. Will of Thomas Wotton TNA PROB 11/70; Letter-Book pp.11, 40, 55.

38. Edward Wotton, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; Walton, Lives.

39. Letter-Book, p.3.

40. Nigel Yates and James M. Gibson, Traffic and politics: the construction and management of Rochester Bridge, AD 43-1993 (1994).

41. Letter-Book, pp. 50, 53, 55, 56, 59.

42. Ibid., pp. 5, 7.

43. Ibid., p.30.

44. Ibid., p. 44.

45. Joan Thirsk, “Agriculture in Kent, 1540-1640”, Michael Zell (ed.) Early Modern Kent 1540-1640 (2000) p.88.

46. Survey p. 93.

47. Letter-Book p.39.

48. BL Add. 38692

49. Retha M. Warnicke, William Lambarde Elizabethan Antiquary 1536-1601 (1973) p. 31; William Lambarde, A Perambulation of Kent (1576) http://books.google.co.uk

50. The British Library Database of Bookbindings http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/bookbindings; Bindings database; http://smu.edu/Bridwell/specialcollections/masterbookbinding/SixCenturiesHighlights.htm; Letter-Book p. xii.

51. Letter-Book p.xii; http://www.south-derbys.gov.uk/Images/BretbyA4complete_tcm21-85585.pdf

The fifth earl was of course the man responsible for financing the excavations which resulted in the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922. Possibly the sale of Thomas’s library helped to pay for Howard Carter’s dig?

The Times 12 March 1936 p.10 col c.

http://www.christies.com/LotFinder/lot_details.aspx?intObjectID=4458238

52. Visitation, op. cit.; Transcript of Boughton Malherbe Parish Register CKS TR2896/48

53. Letter-Book p.41.

54. Will of Thomas Wotton TNA PROB 11/70

55. The Times 12 March 1936 p.10 col. c.

56. Renolde Scot Discoverie of Witchcraft http://www.archive.org

57. Walton, Lives.

58. Letter-Book p.xiv.

59. Letter-Book p.3.

60. Walton, Lives.

61. A. J. Loomie, ‘Wotton, Edward, first Baron Wotton (1548–1628)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004); http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/30000, accessed 1 April 2011

62. Edward Hasted, The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 5 (1798), pp. 397-415. http://www.british-history.ac.uk

III The Wotton Survey

‘The historic landscape [is] a human creation, made from a complex combination of roads, hedges, boundaries, woods, meadows, parks, slag heaps, railway lines and airfields. Buildings, which included castles, churches, country houses, farms, cottages, mills and bridges, contributed to the whole picture of a constantly evolving countryside.’1

Other than slag heaps and bridges, and, obviously, railway lines and airfields, all of the above feature in the survey that was made of the Wotton lands in Kent in the late 1550s. The purpose of this introduction is to describe why and how the Survey was compiled, to give an indication of its content, to set it in its historical context, and suggest how it might be used in research. It is not intended to carry out here any detailed analysis of any of the information in the Survey.

The ancient county of Kent, before boundary changes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, covered just under a million acres. It was the ninth largest English county. The population in the mid sixteenth century was perhaps 80,000.2 It had begun to grow rapidly in the 1540s, with associated social and economic problems.

Map of Kent

William Lambarde, contemporary of Thomas Wotton, and himself a substantial landowner in the county, described Kent in glowing terms:

‘The soile is for the most part bountifull, consisting indifferently of arable, pasture, meadow and woodland, howbeit of these, wood occupieth the greatest portion … except it bee towards the east, which coast is more champaigne than the residue…. It hath corne and graine, common with other shyres of the realme; as Wheat, Rye, Barley and Oats in good plenty.… The pasture and meadow, is not onely sufficient in proportion to the quantitie of the country itself for breeding, but is comparable in fertilitie also to any other that is neare it … In fertile and fruitfull woodes and trees, this country is most flourishing also….

Touching domestically cattel, as horses, mares, oxen, kine and sheepe, Kent differeth not much from others: onely this it challengeth as singular, that it bringeth forth the largest of stature in eche kinde of them: … Parkes of fallow deer, and games of gray conies it maintaineth many…’3

It was the different farming regions of Kent that gave rise to this rich and varied agriculture. From north to south, these regions are the marshlands of north Kent, the chalk of the North Downs, the greensand ridge, the Vale of Holmesdale at the scarpfoot, the Low Weald, the High Weald, and finally Romney Marsh. Although distinctive, these regions were interdependent, with many landowners and farmers having land in several, or all.4

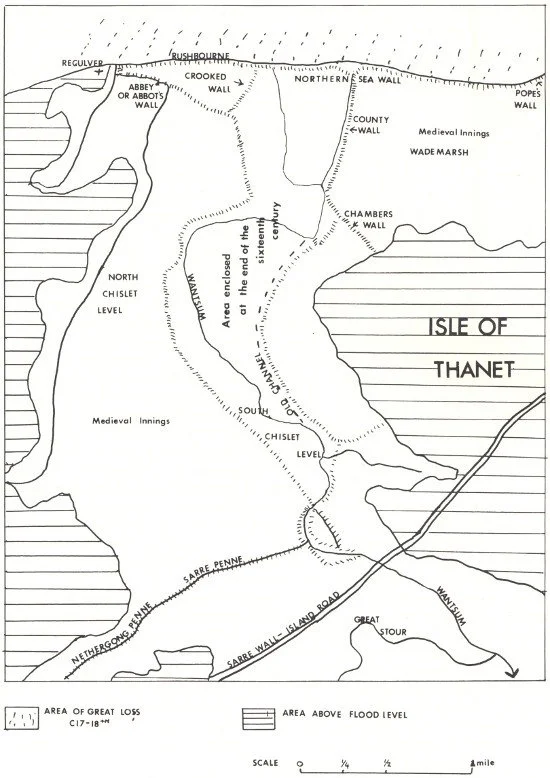

View of the Low Weald from the Greensand Ridge in Boughton Malherbe

The Wotton estates were chiefly concentrated on the greensand ridge, in the scarpfoot and in the Low Weald to the south east of Maidstone, but outlying lands were scattered over the county, from Hadlow in the west to the Isle of Thanet in the east, from Cliffe in the north down to Romney Marsh. There was land in the marshes, on Downland, in Holmesdale and in the Weald. The bulk of the estate, however, was in Boughton Malherbe, where the family’s principal seat was, and in the parishes around.5

The Wotton lands had been accumulated over nearly 150 years, by marriage, inheritance and purchase. The first part of the estate, including Boughton Malherbe itself, was acquired in 1416, when Nicholas Wotton, Citizen and Draper of London, married Joane, daughter and heiress of Robert Corby, a substantial landowner in Kent. Their son, another Nicholas, added Paddlesworth and other lands to the family estates when he married Elizabeth, daughter of John Bamburgh. Nicholas and Elizabeth’s son Robert married Anne, one of the three sisters and heiresses of Sir Edward Belknap. The Belknap inheritance, which included lands in St Mary Cray, in Ringwould and in Lydd, was to cause ongoing problems for Robert and Anne’s son and grandson Edward and Thomas.6

Edward Wotton’s marriage to Dorothy Reed added more lands to the Wotton estates. Edward also made substantial purchases of land during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI. When the Survey was compiled, the Wotton lands in Kent covered an estimated six thousand acres, a very large estate by Kent standards. Possibly only the ecclesiastical landlords and a handful of lay lords had greater estates in Kent than the Wottons. The majority of gentry families in Kent held only one or two manors, their estates totalling a thousand acres or less.7

The Survey was carried out by Thomas Wotton in the late 1550s and early 1560s. Its purpose was to establish what lands he held, where they were, how they were used, the size of each individual piece of land, when and how each piece had been acquired, and of whom and by what tenure it was held. In particular, whether it was ‘of the custom, nature and tenure of gavelkind.’8

Gavelkind was the ancient customary tenure of the county, described in the Custumal of Kent. The earliest surviving manuscript versions of the Custumal date from the early fourteenth century, but the custom itself is believed to be of much earlier date. It was traditionally believed that the ‘Custom of Kent’ was accepted as having the force of statute law in 1293, but elements of it almost certainly date from before 1066.9

According to the Custumal, ‘if a man die seised of landes in Gavelkind ... all his sonnes shall have equall portions.’10 Until 1540, the power of a freeholder to bequeath, or devise, his land by will was limited; however, owners of land held in gavelkind were supposed to have the right to bequeath them by will. This aspect of the custom is disputed, however; it is pointed out that there is no mention of it in the Custumal of Kent, which is the legal basis for the existence of gavelkind.11

It was accepted that lands held directly of the king (in capite) were not gavelkind; lands held of sub-tenants (by socage tenure) ‘are of the nature of gavelkind’.12 The Survey therefore records the feudal tenure by which the Wotton lands were held.

Gavelkind facilitated the emergence of the yeoman class in Kent in the late medieval and early modern periods. Many people had the opportunity to acquire land, by purchase or inheritance, and landownership in the county was broadly based. The custom of gavelkind may have been responsible for the large number of gentry families in Kent in the seventeenth century with modest estates between eight hundred and a thousand acres. Many families had several branches, each established on its own estates. The Boys family was perhaps the most extensive, with ten to a dozen branches. The Finch family had nine branches, the most senior headed by a peer. Each of these separate branches was probably established in the past by a son taking his share of his father’s estates.13

At the lower end of the economic scale gavelkind could lead to the fragmentation of estates, with all the sons of a small landowner inheriting some land, but none of them having enough to support a family. Gavelkind also operated against the interests of the larger landowner who wished his estate to pass on intact to his descendants over several generations.

There were, however, methods whereby landowners could circumvent the custom of gavelkind in order to bequeath their estates intact. One way was to create a ‘feoffment to use’. The land would be held by named feoffees or trustees. The original landowner would have the use, or benefit, of the land, but technically would not be the actual owner.

‘The landowner could provide for younger sons, daughters, bastards, remote relations, or charities, could vary the provision given by law to his widow, and could charge the payment of his debts and legacies on real property .... It was the use and not the legal title which passed on the testator's death.' 14

By about 1500, much of the land in England was held in use, in order to evade the limitations on devising land, and allow the landowner greater freedom in making provision for his family. Boughton Malherbe and other lands of Robert Corby seem to have been held by various feoffees before they passed to Nicholas Wotton.15

A feoffment could also be used to establish settlements or entails which prevented land being treated as gavelkind; these might be continued from generation to generation, thus avoiding the custom indefinitely. In his will dated 27 January 1523, John Roper, Kentish gentlemen and attorney general, created a feoffment to use to ensure that his lands ‘would never be parted among heirs male... going from the eldest issue male to one other the eldest heir and issue male of his [son's] body lawfully begotten for ever, undivided, and not parted nor partible among heirs male.’ 16

Nicholas Wotton the younger, who died in 1480, and his son Robert, who died in 1523, both enfeoffed their lands. Nicholas’s will does not survive. Robert’s will is dated 26 December 1523, just one month before that of John Roper. His intention was to create an entail. He divided his manors of ‘Sherifyscote’ in Thanet and Chilton in Sittingbourne between his sons Edward, Nicholas and George, ‘as gavellkynde lands.’ The manors of Boughton Malherbe, Powcyns and Burscombe, however, he willed either to Edward or Nicholas or George in their entirety 'never to be divided or departed'. The specified lands were then to pass to the eldest sons of the three heirs, and, failing legitimate issue of any of them, to pass to the survivor or survivors. In the event both George and Nicholas died without issue, so all the lands ultimately passed to Edward’s eldest son Thomas.17

Feoffments to uses were also a means of avoiding feudal dues to the king, thus reducing the Crown’s income. The Crown initiated a test case in Chancery, based on an inquisition into the estates of the late Thomas, Lord Dacre, who died in 1534. The inquisition was held at Canterbury, so Kentish gentlemen would have been well aware of the case. The Statute of Uses, which ensued in 1536, attempted to restrict the way in which feoffments were used. The Statute aroused opposition among gentry in some parts of England; it was a factor in the risings in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, in the autumn of 1536. Some of the objections to the Statute of Uses were dealt with by the Statute of Wills, 1540, which gave freeholders the right to dispose of freehold land by will. This was of no assistance to landowners who wished to dispose of gavelkind land, however. If they had been using feoffments to uses to circumvent the custom, they now had to find other means.18

Gavelkind tenure could only be altered by Act of Parliament. Some disgavelling took place in the early medieval period, and Acts were passed in the eleventh year of Henry VII and the fifteenth year of Henry VIII to disgavel the lands of Sir Richard Guldeford and Sir Henry Wyat. Then in 1539 an Act of Parliament was passed to disgavel the lands of thirty four gentlemen, including Sir Edward Wotton. This was the year in which legislation to dissolve the remaining monasteries was passed; many of these gentlemen would add to their estates when the monastic lands came onto the market. A second disgavelling Act was passed in the third year of Edward VI, 1549. Forty four men were named in this Act, including Edward Wotton and eleven others who had already had lands disgavelled under Henry VIII.19

The second Act was passed against a background of controversy at court, with the scheming, fall and eventual execution of the Protector's brother Thomas Seymour, and economic depression and public disorder in Kent. In the summer of 1548 about five hundred people pulled down recent enclosures of Sir Thomas Cheyney, one of the men whose lands were disgavelled. Enclosures of Sir Thomas Wyatt were also torn down. There were rebellious assemblies outside Canterbury and on Penenden Heath. ‘Popular disturbance was almost endemic in Edwardian Kent.’ Peter Clark suggests that the disgavelling may itself have been a cause of the disorder, along with enclosures, engrossing and rack renting. ‘Though it is not certain how far tenants saw disgavelling … as a threat to their rights, they may have regarded it as part of a general attack on peasant rights and customs.’20

The disgavelling may have been a response to the Dissolutions, which changed the pattern of landownership in Kent more than in many other counties. Elton suggests that confusion was created when Henry VIII made grants of former monastic lands without considering under what tenure the lands had been held before they came into the possession of the religious houses. ‘Much land, which was at first gavelkind, had come to be held in knight service [i.e in capite, and thus not subject to gavelkind], and yet the customary descent remained.’21

Thomas Cromwell heads the list of names in the first Act, and the name of Sir Christopher Hales, the Master of the Rolls, also appears, suggesting there was official impetus behind this legislation. Edward Wotton himself was a courtier in the reign of Henry VIII and a Privy Councillor under Edward VI. Many of the families that would be active in county affairs for the next century or more were associated with the two Acts - Culpepper, Darell, Harlakenden, Harte, Hussey, Lovelace, Moyle, Roper, Scott, Walsingham.22

There were no doubt also economic and personal reasons for the disgavelling. Zell suggests that the landowners ’may have believed that the transmission of their estates to their chosen heir would be more secure if their land shared the same common-law, impartible tenure by which most other English landowners held their estates. Or it may have been merely a matter of prestige to distinguish their estates from those of lesser men.’23 There may have been a fear that Henry VIII, having done away with the traditional practice of enfeoffment, might have turned his attention next to customary practices such as gavelkind; these landowners might have wished to protect themselves by bringing their estates within the framework of the common law.

Further research might show whether the impetus for the disgavelling came from the government, from the emerging county community, or from a group of courtiers, office holders, incomers and non-resident gentry wanting to adapt the customs of the county to their own benefit.

It was assumed that all land in Kent was gavelkind unless it could be proved otherwise. In the absence of any evidence that land had been disgavelled, it continued to be treated as if it was gavelkind. Demonstrating that land had been disgavelled was not necessarily easy. The disgavelling acts were private Acts. They were presented to Parliament in the form of petitions, which were either assented to, or not. Private Acts were not normally published; the second of the two disgavelling Acts was not printed. Nor, during the period in which the disgavelling Acts were passed, were private Acts routinely included in the Parliament Roll, the official listing of all statutes. There was thus sometimes no public record of the passing of such Acts.24

Since the disgavelling Acts are referred to by Hasted and other authorities on landholding in Kent, it must be assumed that they were not forgotten. However, there was no publicly available schedule specifying precisely which lands were covered by the legislation. In order to ascertain whether any piece of land was still subject to gavelkind, it was therefore necessary to examine ‘the inquisitions post mortem of the owners before and after the date of the Acts, the Patent Rolls for the date of any grants to them of lands taken from the monasteries, and the licenses of alienation (or pardons for aliening without license) of lands disposed of during their lives, and other records’25 Hence the necessity for the survey of the Wotton lands, to establish which were still of gavelkind tenure following the two disgavelling Acts.

The Survey was still in use in the early seventeenth century. A note regarding the sale of Pettes in Bredgar records the sale price which has come ‘to your lordships use’.26 This note must have been made after Edward Wotton was ennobled in May 1603. The history of the Survey subsequent to this is uncertain; it is not certain whether the owner of the Wotton lands at any time was aware of its existence, or the nature of the tenure of the lands which they held. Even before the greater part of the estate was purchased by Galfridus Mann, some of the land was sold piecemeal. The Survey is annotated with details of land disposed of even at the time the Survey was being compiled, or soon after. Much of Bynwall marshe in Iwade was sold to Myldred Taylor. The entire manor of Paddlesworth was sold to the Marshams of Cuxton in the mid seventeenth century.

Seventeen acres of woodland in Burscombe in Egerton were sold in 1699. Thirty six acres of woodland in the manor of Colbredge in Boughton Malherbe were sold in 1700. It is possible that the new owners of the disgavelled lands were unaware that they were no longer subject to gavelkind. Research into wills and family papers of subsequent owners of the Wotton lands may reveal whether or not the lands were treated as though they were still subject to gavelkind.27

*****

Sixty seven discrete units of land were surveyed, including the demesne lands of twenty manors. They range from large manors such as Colbredge in Boughton Malherbe, to moderately sized ‘messuages and tenements’ or farms such as Robyns Tenement in Lenham, to small plots of land such as Goldhurdfeeld in Lenham. The description of Colbredge is nineteen pages long. That of Goldhurdfeeld is just two pages.

Each section begins with a preamble, stating the name of the land being surveyed, and when and by whom the surveying was done.

‘The boundes or lymetes and contennt or quantitie of allthe Demeane landes of the manoure of Ryngewolde, lyenge in Ryngewoolde in the Countie of kennt.’

‘The boundes or lymetes: and contennt or quantitie of certainelandes called Powcynes, lyenge in Bocton malherbe in the Countie of kennt.’

The parish in which the land lay was always stated. However, some manors extended over more than one parish, so some of the lands surveyed might lie in a parish or parishes other than the one named in the preamble. The demesne lands of the manor of Mynchincourte alias Fryringcourte lay in Shadoxhurst, Orlestone, Warehorne, Snave and Woodchurch. The manor of Wardones, in Egerton, had meadow in Charing. The manor of Burscombe in Egerton extended into Charing and Boughton Malherbe.