An Inscribed Roman Altar Discovered at Napchester, near Dover

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

Thomas Vicary A Famous Maidstone Surgeon

Plans of and Brief Architectural Notes on Kent Churches - Part IV

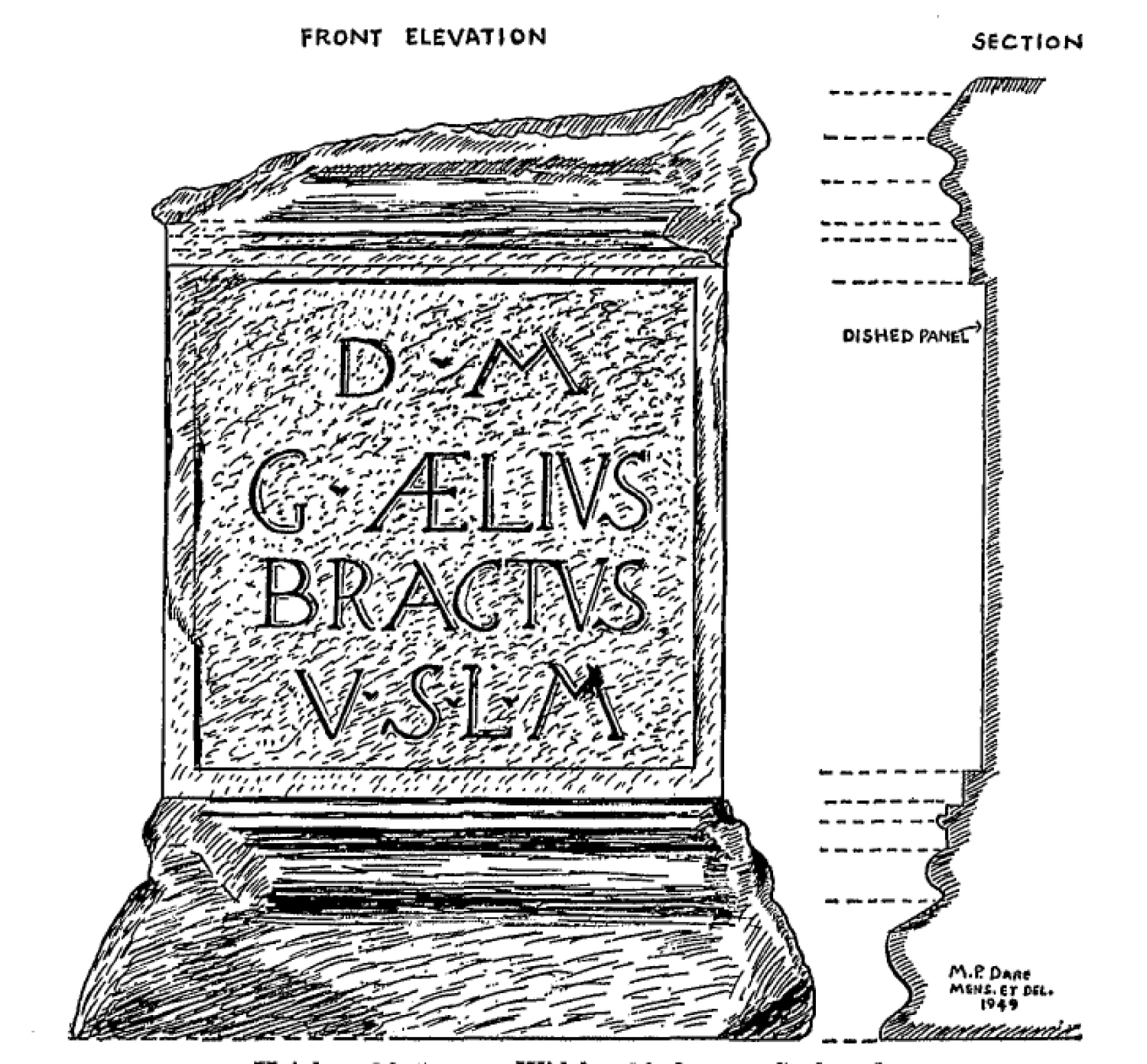

AN INSCRIBED ROMAN ALTAR DISCOVERED AT NAPCHESTER

NEAR DOVER

By M. P. DARE, M.A.

THE small Roman altar here illustrated was discovered by me on

August 5th, 1949, at the small hamlet known as Napchester, on the

Roman road which connected Rutupise (Richborough) with Dubris

(Dover). I have presented it to Dover Museum, whose war-damaged

collection is being reconstructed by the Honorary Curator, Mr. F. L.

Warner, in premises at Ladywell, Dover.

FRONT ELEVATION SECTION