Plans of and Brief Architectural Notes on Kent Churches - Part IV

Search page

Search within this page here, search the collection page or search the website.

An Inscribed Roman Altar Discovered at Napchester, near Dover

St. Augustine of Canterbury and the Saxon Church in Kent

PLANS OF, AND BRIEF ARCHITECTURAL NOTES ON, KENT

CHURCHES

PART IV. TROTTESCLIEFE, SS. PETER AND PAUL, BISHOPSBOURNE,

S. MARY, AND ADDITIONAL NOTES ON BEARSTED

By F. C. ELLISTON-ERWOOD, F.S.A.

TROTTESOLIFEE. SS. PETER AND PAUL (Plan 15)

TROTTESOLIFEE (or Trosley) Church is a small simply planned bufiding,

consisting of a nave and chancel without any chancel arch, to which

has been added on the south-west corner, a late tower. I had always

regarded it as an early Norman church without any peeuHar or unusual

features and it was, therefore, somewhat of a shock when a sheaf of

papers, sketch plans, measurements and photographs was handed to me

for study, for therein was propounded the theory that the eastern

portion of the building was the earher, to which at a later date had been

added the present west part of the church, now the nave. This in

itself would not be an impossibility, but the manner in which it was

suggested the addition had been made was certainly unusual. A study

of the accompanying plan (No. 15) shows that the exterior of the church

is devoid of any noteworthy features except the two projecting angles

(a' below) in the middle of each of the north and south walls. One

of the sketches in the coUection above referred to was something Hke

this:

FIG. 1

The purport of it was that the eastern part had been first built and

later its west wall had been removed, and the two ends of the lateral

waUs inserted into a new extension westwards in the manner shown,

which was held to account for the position of the various angle projections.

Such a method of church extension was unknown to me,

so in view of the forthcoming visit of the Society to the church (May,

1949) I determmed to investigate the problem. I made a plan, and

in this case I took unusual precautions to ensure the correctness of my

measurements, especiaUy regarding the position of " a " and " a',"

99

NOTES ON KENT CHURCHES

b

I

8

100

NOTES ON KENT CHURCHES

and the result was as I suspected, the exterior and interior coins were

in a straight line and not as shown in the sketch above. That point

being settled, the history of the fabric becomes much easier to read.

It is that of a simple early Norman church, merely differing from the

more usual plan in the greater length of its chancel, of which there are

several examples, notably Darenth (Arch. Cant., LXI (1948), Plan 11).

I cannot discern any factors that would differentiate in date between

the eastern and western parts of the church. The coins aheady

mentioned and those at the east end of the church are all of tufa, and

save where obvious repairs have taken place, they are indistinguishable

one from the other. The factor that might have helped would have

been the character of the western angles, but these have been completely

destroyed, and the west wall (in itself a good piece of knapped flint

technique) with its coins is modern work. The position of the chancel

arch, now removed, may give rise to some doubt. I should have

preferred it east of the interior coins but a window of twelfth century

date, which to my mind is in situ, precludes its being placed there,

so there is no alternative but to place it as on my plan. The notes

aheady mentioned recognized the same difficulty, and got over the

problem by stating that the window in question had been moved from

further east, opposite a similar one on the north, and where now a

Decorated window takes its place, but I can see no evidence for this,

and I doubt very much whether there would have been in the fourteenth

century much soHcitude for a small and no doubt weathered Norman

window. The thirteenth century saw the insertion of windows and

a doorway in the nave, but the great building period was the fourteenth

century, when in addition to other windows and a small piscina, a

somewhat massive tower was erected at the south-west angle. In the

early church there was no provision for a tower, so when one was needed

it was built with its thick walls up against the south-west corner of

the nave with the result that the church is entered through some

7 feet of wall. The floor space is very small and now it is divided

into halves by a wooden screen to form a small vestry. There does

not appear to have been any means of access to the upper part of this

tower from within, but on the interior nave wall, above and to the west

of the existing door, is a blocked-up opening that suggests a door and

an ascent by a ladder inside the church The only other feature of

note is a large insertion of recent brickwork that may probably indicate

a window (or a chancel door) now removed, and the place patched up

with brick.

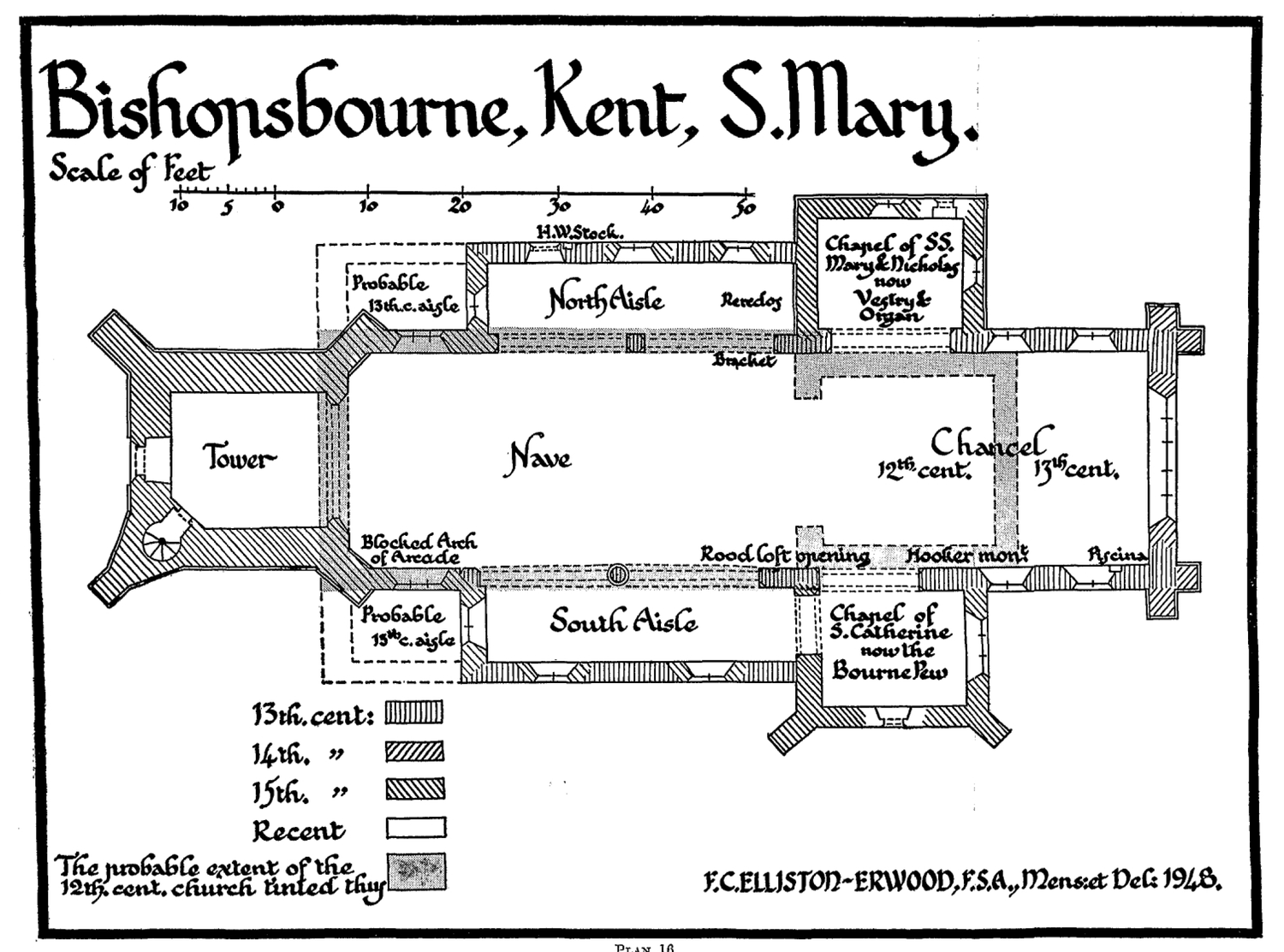

BISHOPSBOURNE, S. MARY (Plan 16)

Bishopsboume is a smaH, rather obscure village situated in a

vaUey below Barham Downs, and is famous for its literary associations

101

NOTES ON KENT CHURCHES

with such diversities as the sainted Hooker and Joseph Conrad rather

than with architecture, but both Bourne House and the church are

not without interest. Unfortunately the latter has undergone one

or two rather drastic restorations with the result that though the

fabric is to-day in very good condition, any vestiges of early structures

are almost non-existent. It would be too much to expect anything of

the pre-conquest church that almost certainly stood here, but of its

successor, the twelfth century church, I failed to detect a single stone,

and my suggestion for the building of this period, as shown on my plan

in a stippled tint, while almost certainly correct, finds no confirmation

in existing fragments. But taking it as a foundation, it is clear that

the church was considerably enlarged in the thirteenth century by the

addition of aisles to the nave and by a widening and extension of the

chancel. Architectural features belonging to this time are : The north

door in the north aisle with an external Holy Water stock, the nave

arcades (though the arches themselves have certainly been rebuilt)

and practically the whole of the chancel and its windows, except that

in the east. It is highly probable that the arcades each had an extra

bay to the west; traces of the arch on the south still remain, though

that to the north had entirely disappeared. Fourteenth century work

is negHgible, and is confined entirely to the east wall, where a larger

window was inserted and buttresses added. The following century

was, however, a very busy one, the chief addition being the western

tower. Till this time there was no tower and probably this feature was

due to the Hawte family, who then held the manor. The whole of the

west end of the church was taken down, together with the two western

arches, the tower was built in its entirety with four large angle

buttresses and then it was united with the body of the church by

new waUs on the Hne of the arcades, and new west ends to each aisle,

which were thereby reduced to their present dimensions.

Further additions belonging to this period were the two chapels to

the north and south of the chancel. That to the north, now occupied

by the vestry and the organ, still preserves enough of its fittings to

be certain that it was intended for a chapel, probably dedicated to

St. Nicholas. That to the south may be the chapel of St. Catherine

but is now, and for some time has been, known as the Bourne Pew and

bears no traces of piscina or altar fittings. This, of course, is not

unusual as such things were often removed at reformations or restorations.

This is in brief the architectural history of the church, though

the Hooker Library and monument, the window near the rood loft

doorway (designed in all likelihood to give more light to the rood

loft), the glass of several periods, some woodwork in the Bourne Pew,

the brasses, plate, beHs and the ancient font lying neglected near the

newer and meretricious specimen of 1850, are all worth examination.

102

Btsf^^boume,Kmt, SJTLn^

Scale of Yeefr

J l u n l n nl

1o 5 0 \o ^0 -p J* •%

[ JVo6a£Ce,

owr- J *

BG>c£«Ctt«K

TwGfcGCe

| 1S*C.J^C»

)Ct£AisG, Jkvufe$

WMMV 1 lF=Mf

l ip

I !

HI

awe

CfvaijtdeL

J^ccnt: {T^sent,

i i

r—i

_ _ _, Ji^^i*>fc

i i

m

yftfc » ^

1_™

ra

I

w

I Tixa tttoGaBCe atfX&rCC o f t&Zy, I

' l&t^