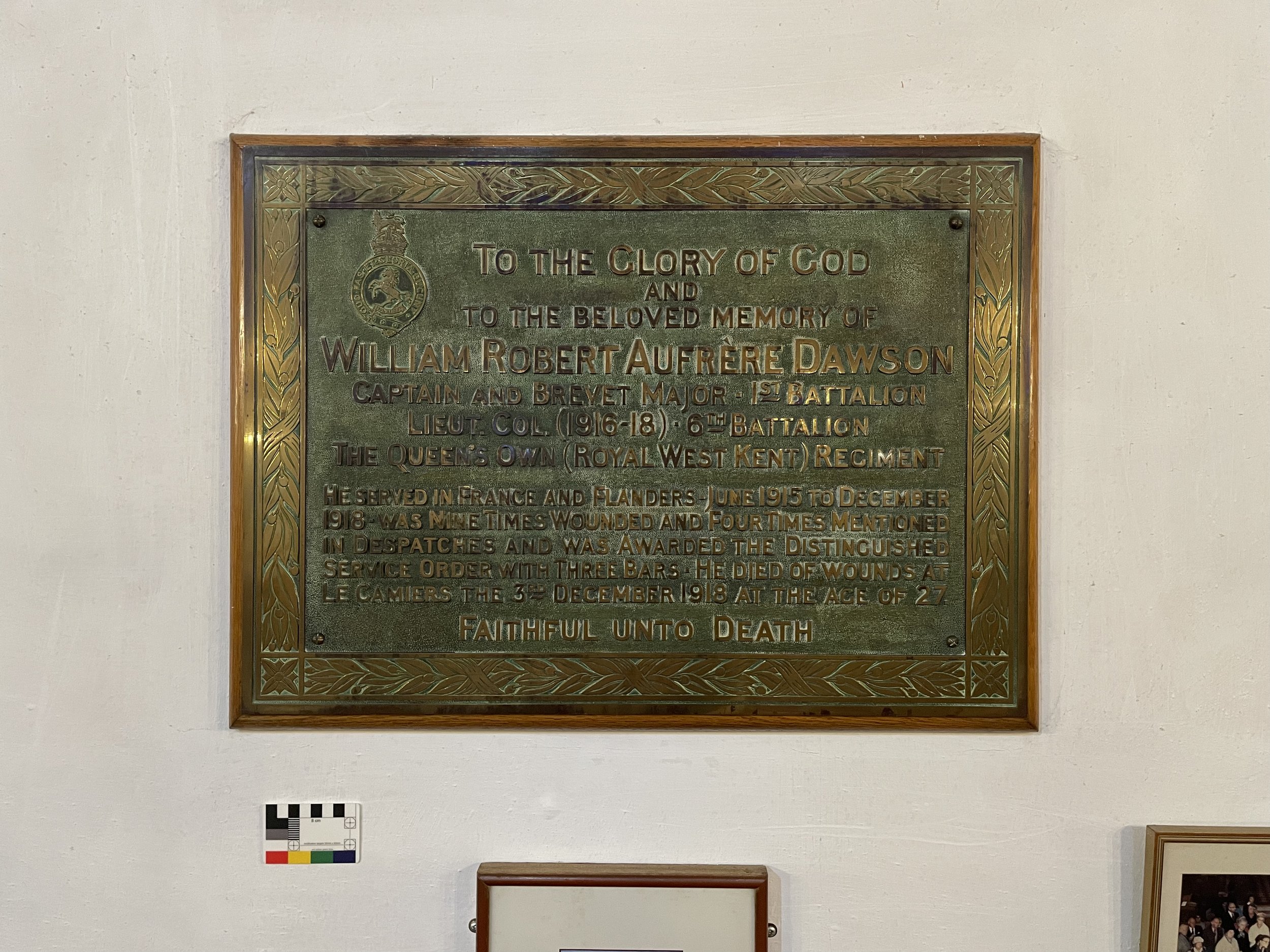

Monuments of the interior of St Margaret of Antioch Church, St Margaret’s-at-Cliffe

Recorded by Geoff Watkins and Jacob Scott as part of the Virtual Tour of the church.

Monumental Inscriptions with concise wills of Gravesend & Milton Cemetery

Monumental Inscriptions of Gravesend & Milton Cemetery with concise wills from the first two decades 1839-1859. Recorded by David Edward Williams, 15th June 2025.

Monumental Inscriptions in the church and old churchyard of St Michael, Chart Sutton

Monumental Inscriptions with concise wills. Transcribed by D.E. Williams 2024.

Introduction to the Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

The Rochester Bestiary is a splendidly illuminated manuscript depicting wild beasts, domesticated animals and mythological creatures from around the known world. An ongoing translation project by Gabriele Macelletti and a transcription by Dr Patricia Stewart.

Lion, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, ff3r-5r. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Tiger, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, f6r. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Leopard, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, f7r. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Panther, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, ff7r-9r. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

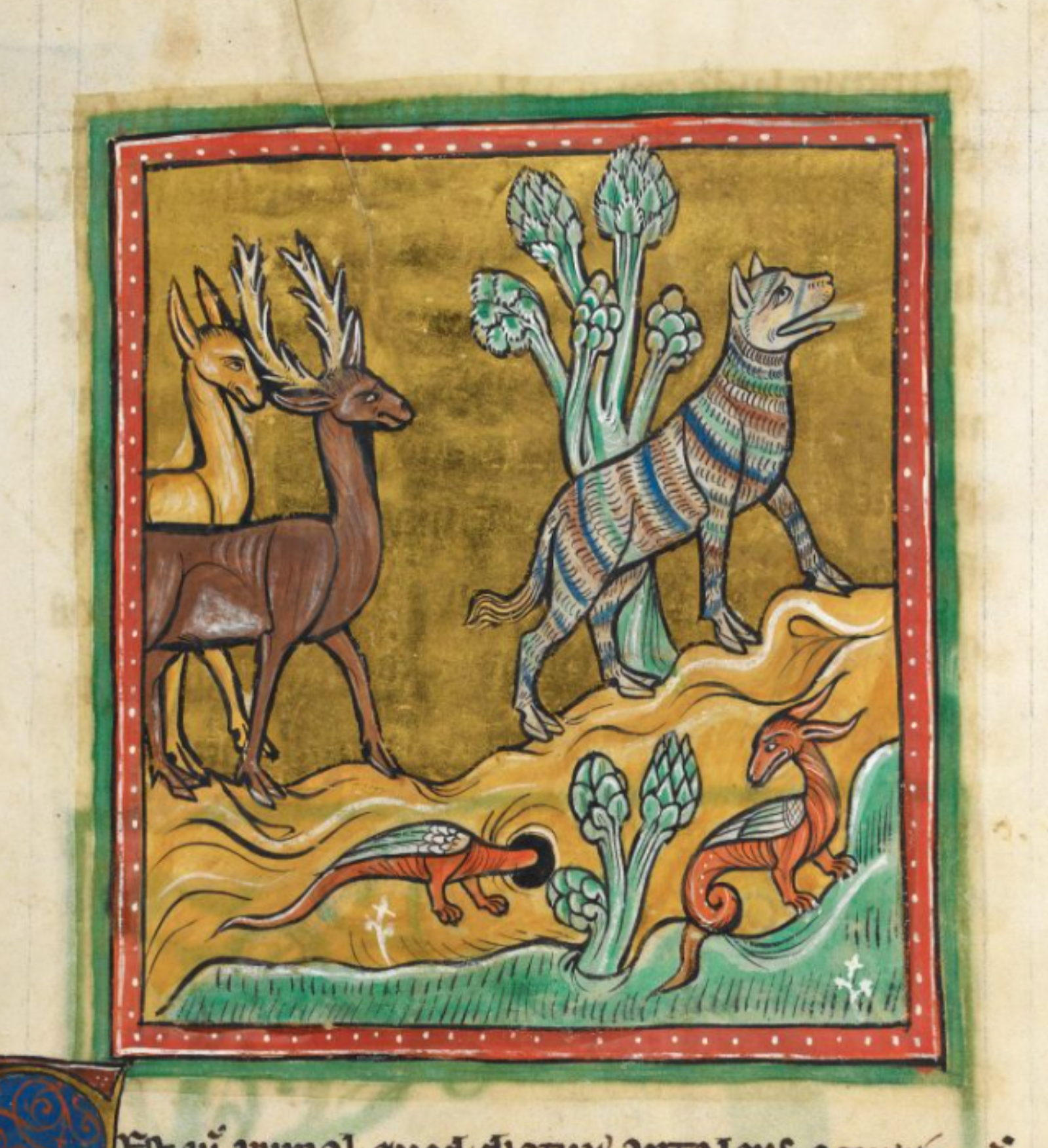

Antelope, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, ff9r-9v. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Unicorn, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, ff10r-10v. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Lynx, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, ff10v-11r. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Griffin, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, ff11r. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Elephant, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, ff12r-13v. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Beaver, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Ibex, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, ff14r-14v. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Hyena, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Bonnacon, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Satyr, Rochester Bestiary, c.1230

Rochester Bestiary, f17v. British Library MS. Transcription by Dr Patricia Steward. Translation and commentary by Gabriele Macelletti.

Tags

- Accounts

- Adisham

- Alkham

- Ash-next-Ridley

- Ashford

- Aylesford

- Bekesbourne

- Betteshanger

- Biddenden

- Brenzett

- Bromhey

- Bromley

- Canterbury

- Capel

- Chalk

- Charing

- Charters

- Chatham

- Chelsfield

- Cliffe

- Cooling

- Cranbrook

- Custumale Roffense

- Cuxton

- Dartford

- Deal

- Dover

- Eastbridge

- Eastry

- Faversham

- Fawkham

- Feet of Fines

- Folkestone

- Food

- Frindsbury

- Gillingham

- Goudhurst

- Gravesend

- Haddenham

- Hadlow

- Harbledown

- Hawkhurst

- Hawkinge

- Higham

- Hoath

- Hoo

- Horton Kirby

- Hythe

- Ifield

- Inscriptions

- Ivychurch

- Lamberhurst

- Laws

- Lewisham

- Littlebourne

- Lydd

- Lyminge

- Maidstone

- Medicine

- Medieval

- Military History

- Modern

- Monasticism

- Monumental Inscriptions

- Newenden

- North West Kent Family History Society

- Northfleet

- Orlestone

- Preston near Wingham

- Rainham

- Ramsgate

- Records

- Ringwould

- Rochester

- Rochester Cathedral

- Saltwood

- Sandwich

- Shipbourne

- Shoreham

- Sittingbourne

- Snargate

- Snave

- Snodland

- Snodland Historical Society

- Stansted

- Stoke

- Stone in Oxney

- Stourmouth

- Stowting

- Strood

- Sturry

- Surveys

- Tenterden

- Textus Roffensis

- Tithe Commutation Surveys

- Tonbridge

- Westwell

- Wills

- Woolwich

- Wouldham